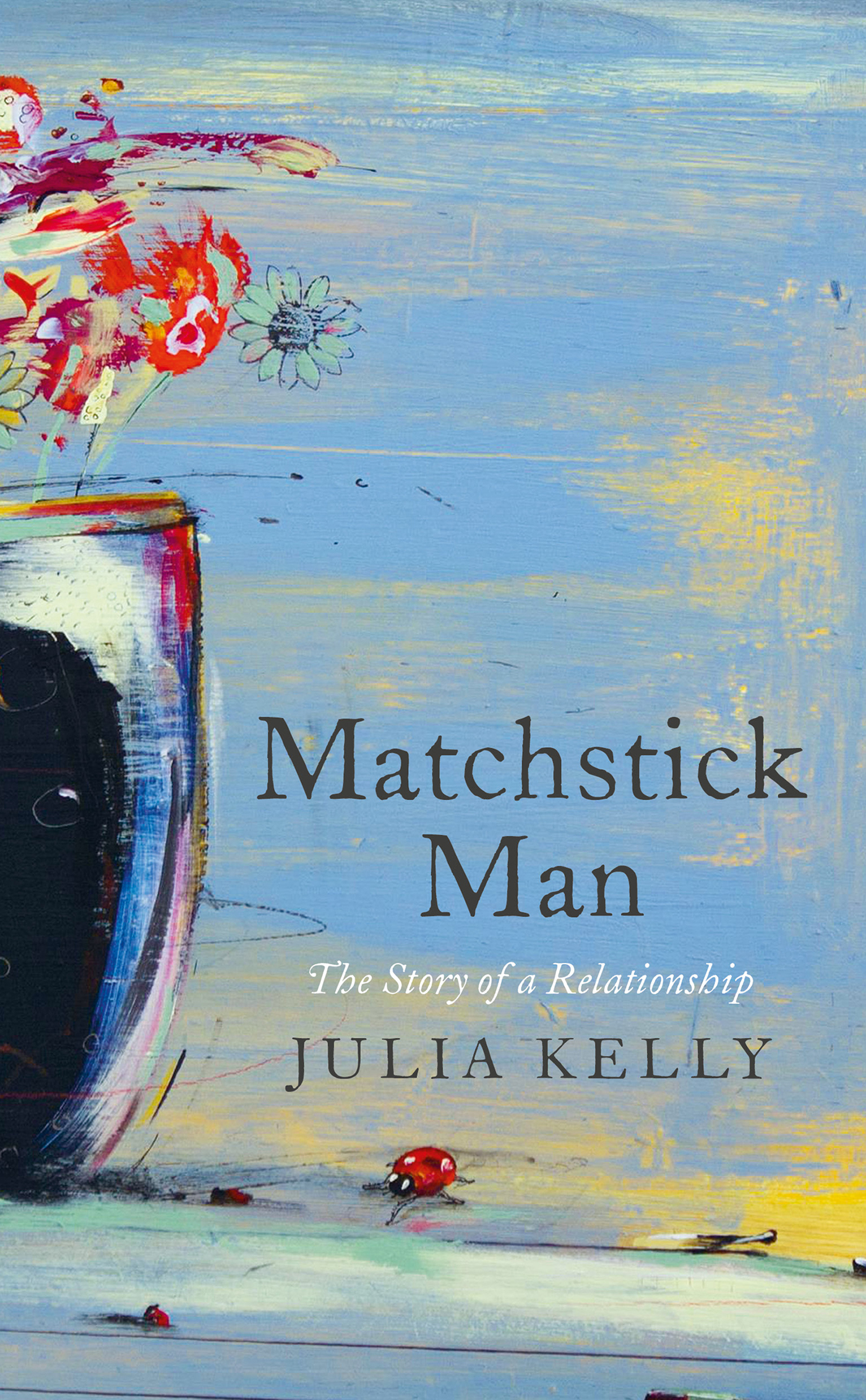

MATCHSTICK MAN

The Story of a Relationship

Julia Kelly

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

A brilliant artists mind begins to collapse. This is a story you will not forget, written by his partner with unsparing love and honesty.

Matchstick Man is the story of a minds disintegration and its effects on the family of the man they are losing to confusion, distress and amnesia. From the first disturbing signs, to the fall into bewildered helplessness, this beautiful, moving book traces the pitiless reality of Alzheimers disease as few other pieces of writing have ever done.

Julia Kelly is an Irish novelist. With her partner, the artist Charlie Whisker, she lived a life that seemed glamorous and carefree a world in which their friends were rock stars and other artists and writers. Charlie helped her to become a writer, and together they had a daughter. Matchstick Man describes heartbreakingly and unsentimentally their loss of innocence, and Julias discovery that even love cant defend them against this cruel illness.

Contents

For Charlie, my mentor still

Now is the best place to begin. Now is what we still have and what Charlie has left. The future is nebulous; the past is dissipating, shifting, elusive, more difficult to access each day.

It is seven in the evening, three days before Christmas 2014. We are all at my sisters house in Blackrock, outside Dublin. Her small home seems to swell and sweat with our accumulated movement and noise. Potatoes are roasting in the oven, the kids are slumped with their tablets and gadgets in the sitting room, Silent Night is on the radio.

Im in the kitchen trying to sort out the fridge. Its so full that the door wont close. Ive removed and rearranged things several times, taking litre bottles of Coke and 7Up from the side sections and lying them down at angles in the main part. Each time I try, the seal will stick, but seconds later it will pop open again a dark gap where there should be light emitting a blue-cheese reek that further weighs down the stagnant air.

I can hear the sound of our daughters laughter as her dad tickles her in the hall. There, at least, there is a sense of space and the soothing scent of pine needles from the tree in the corner, hemmed in by a thick scattering of gifts, its branches brittle from the heat and dragged down by the weight of coloured baubles.

He says her name, Nipey, not the one wed given her at birth but what he likes to call her, and the name I will use for her here. Do it again, Dad! she shrieks. Theres a manic edge to her small voice, as if shes almost unable to tolerate whats ahead. I picture her, eyes bright, beaming, her little limbs flailing about. I silently will her not to kick him, to try her best to stay happy and calm.

Again! Please Dad, dus one more time. And he tickles her again but then gets irritated by their game, her five-year-old energy too much for his sixty-five years. Her voice thins to a whine. Then the sound of her crying, Charlies swears, the slam of the front door.

I curse, run up the stairs to the hall, give my child a careless, distracted hug that does nothing to comfort her. I open the front door and call after him.

I cant fucking stand it! Its like a fucking drill in my head! he shouts into the darkness as he strides down the garden path black, angular, furious turning left out the gate as if he knows exactly where he is going.

This morning, finally, there had been no more sleeps till her father was coming to stay. In preparation for his visit she had constructed a den using upturned chairs and blankets in our temporary bedroom. It had collapsed several times and shed tearfully blamed me for not holding my end properly. When it was at last stable, she climbed in to try it out for herself. Perfect. This was where she and her dad would eat their ice-creams after tea.

We had been staying at my sisters since the sale of our home a month before. I had found a flat for Charlie nearby but though we saw each other every day, visits had to be kept short because he had become acutely sensitive to noise. And the noise that was least tolerable to him was that of his young daughter, whom he otherwise adored. Lately she had come up with a new way of talking to him, using grown-up hand gestures and a slow, careful way of explaining things. When she was like this he would encourage her into his arms, and she would find that familiar, warm space beneath his armpit and nuzzle in, curling her legs under her. But if she forgot this new self and became five again giddy, excitable, silly he would disentangle himself, get up, leave the room and lie on his bed in the dark, his hands clasped over his ears.

She had made a pictorial list of how the day of the sleepover would go and had crossed off three of the drawings on it before things had all gone wrong. Wed gone first to the playground in Blackrock Park, where wed seen a family of swans mother at the front, five cygnets in the middle, father at the back waddling across the playing field in a tidy row. Wed abandoned the swings and had escorted them as they tottered back to the pond, along with an amused gathering of dog-walkers and kids. Charlie knew about animals so he took charge, gently dissuading children from getting too close. They inched down the steep slope above the pond, the cygnets sliding along on their backsides, flopped into the water and glided away, still in a perfect row.

Wed done some Christmas shopping after that not in the city centre but in the less busy, less potentially overwhelming, village of Blackrock. Id bought Charlie a shirt. Hed bought me a top and a Beanie Boo toy for the Nipe. Then wed gone to a caf close to my sisters for hot chocolate. Thered been a moment when Charlie wanted something on the table but somewhere between the realization and the reaching out he had forgotten what it was that hed needed. All three of us watched his hand hover uselessly in the air. Mum, he wants you to hold it, Nipey whispered, her cheeks reddening at the idea. After dinner I would run him a bath, and wed promised our daughter that we would all go to bed at the same time, the prospect of which couldnt have been more satisfying to her.

*

I follow him down the road now, frightened, still shouting his name, still telling him angrily to calm down, but Charlie is swift and nimble on his feet: he ducks behind cars, takes sudden sharp turns, and I cant keep up with him. By the end of the road I have lost him. I want to lose him. I hate him. He is ruining our Christmas. He is damaging our child. But I also urgently need to find him, to comfort him, to know that he isnt in danger.

I run back to the house. My daughter is wedged between her cousins on the sofa in the sitting room, quiet and compliant, the way she always is when she senses that shes done something wrong. I need to tell her that it isnt her fault, that her father is very unwell; but that will have to wait till later, till I have found him and brought him home safe.

We leave her teenage cousin in charge and drive through the village, my sister at the wheel, beneath luminous snowflakes, flashing neon reindeer, laughing snowmen. We scan streets busy with shoppers harassed, preoccupied, burdened with too many bags. None of them is Charlie, none of them even know him or us or anything about our crisis, their day is continuing as before.