Introduction by Jules Zanger

Skyhorse Publishing

JULES ZANGER was born in New York in 1927. He studied at the University of Denver and the University of Chicago, and received his Ph.D. at Washington University in 1954. He recently edited Diary in America by Frederick Marryat, published by the Indiana University Press. His articles have appeared in New England Quarterly, Nineteenth Century Fiction, and the Newberry Library Bulletin. He has taught at Ohio State University and Illinois Institute of Technology. He is presently an Assistant Professor in the Humanities Division at Southern Illinois University.

Copyright 2013 by Jules Zanger

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

eISBN: 978-1-62873-843-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data [TK]

ISBN: [TK]

Printed in [TK]

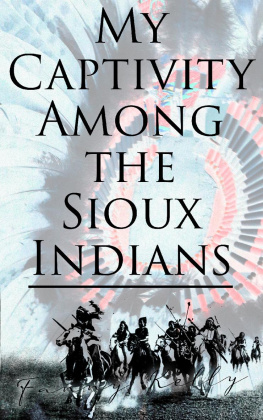

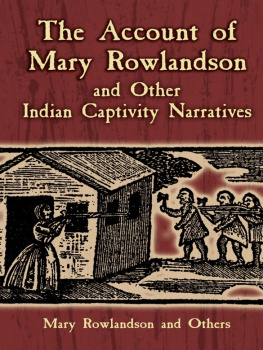

MY CAPTIVITY AMONG THE SIOUX INDIANS

This republication of Fanny Kellys Narrative is a complete and exact reissue of the original edition, published in 1871, including all the original illustrations. Only the placement of the engravings has been rearranged slightly to facilitate this reissue of a unique document.

Even during the Civil War, the relentless western movement went on. The pioneers faced not only the hardships of the covered wagon trek, but also the ever present problem of the Indians. It is against this American scene, that Mrs. Kellys harrowing narrative unfolds. Her first question upon meeting a white man after her release was, Has Richmond been taken?

INTRODUCTION

The Indian captivity narrative, though it has antecedents and parallels in other cultures, developed as a particularly American literary form. It appeared, flourished, and declined during the three hundred odd years of American experience on the Indian frontier: three hundred centuries during which the Indian presented an obstacle to the expanding civilization of the white man. With the disappearance of that frontierand with it of the threat of the Indianthe captivity narrative lost its last attenuated connection with reality, and it, too, disappeared, merging finally with the stream of Western sensational literature.

During those three centuries of frontier experience, the captivity narrative was to suffer considerable alteration. In its beginnings in Puritan New England, it appeared as a concrete, detailed account of trial and fortitude, illuminated by an intense conviction of Gods mercy. Because almost every such narrative had been written after the captive had been rescued or ransomed or had escaped, it was the experience of redemption which gave intensity and significance to the account of the trials suffered. For the Puritan, the captivity narrative was both concrete evidence and symbolic testimony of Divine Providence.

Later audiences, however, were to find the sensational details of the captivity more exciting than its symbolic significance. The religious intensity of the early narratives was replaced in the eighteenth century by a merely formal piety, and the narrative became increasingly a propaganda vehicle concerned in the main with revealing the cruelty and barbarity of the savages and their European allies. Though it was to be modified at times, it was this view of the Indians which the captivity narratives were to present until the final destruction of the Indian power.

This propaganda function of the narratives of captivity was to merge in the late eighteenth and nineteenth century with the Gothic horror story and the novel of sensibility, producing accounts which grew progressively more sentimental and more shocking. The female captive, because of her greater potential for pathetic effects and because of the excitement she created as an object of sexual interest, all but crowded the male captive off the scene. Those authentic, detailed accounts which make the earliest narratives valuable to the anthropologist and the historian were, in the nineteenth century, replaced by stylized, semi-fictional pastiches of gore and sentimentality confected by hack writers more concerned with reproducing the popular image of the Indian than with authenticity.

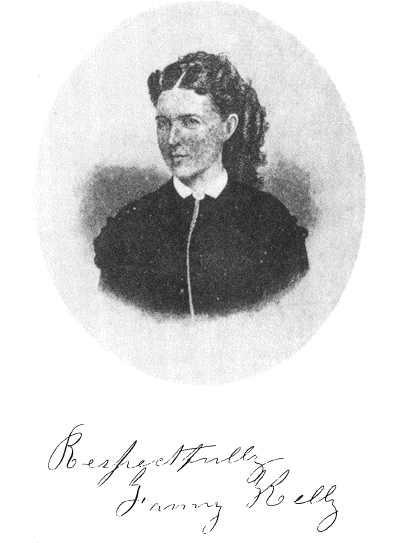

It was at this lean latter end of the captivity narrative that Mrs. Fanny Kellys My Captivity Among the Sioux appeared. Travelling to Idaho with an emigrant train from her home in Kansas, the nineteen year old Mrs. Kelly was captured west of Fort Laramie by a band of Ogalala Sioux on July 12, 1864, and held prisoner until December 12 of that year, when she was released at Fort Sully in the Dakota Territory. First published in 1872, under conditions made clear in the text, her narrative came buttressed with affidavits from Army officers and Indian chiefs, attesting to its authenticity in a period when most such accounts were more fiction than fact. Her book is clearly one of the most distinguished examples of the last period of the captivity narrative. Although Mrs. Kellys work contains most of the standard elements of the nineteenth century captivity, her sentimental passages, her flowery nature descriptions, her pious and patriotic effusions exist as isolated set-pieces, and the detailed and exciting account of her actual experiences is never obscured by them. She is capable of referring to the squaws who guard her in Cooperesque terms: as forest belles, or as artless maidensbut she rejects scornfully and sadly the noble savages of popular literature. At moments in her narrative, she intrudes elaborate, full-blown descriptions of sunsets and mountain storms, but she seldom permits her effusive sensibility to spill over into the adventure itself. On the whole, Mrs. Kelly remains an extra-ordinarily level-headed young woman throughout her ordeal. On her liberation she offers the traditional paean of Thanksgiving, not to the Almighty, but to the Flag of the Republic, and equally illuminating of her character is the fact that among the first words she speaks to a white man after she has been taken captive are, Has Richmond been taken?

Mrs. Kelly shines through her tale as a woman of genuine courage and ingenuity, and as an observant and sensitive recorder. However, what most significantly distinguishes this account from the dozens of others which it superficially resembles is an ambivalence of motive which produces at times a kind of unconscious irony in her narrative. Although Mrs. Kelly explicitly professes a most unambiguous hatred toward the Indians for their treachery and cruelty, she betrays a more complex attitude by including throughout her account many examples of white treachery, cruelty, and injustice toward the Indians, which considerably weaken her indictment of her captors. Describing a campsite close to which her party was attacked and her companions slain, she remarks that it was near this location that General Harney had, some years before, massacred a group of Indian women and children. In a chapter devoted almost exclusively to the deceitfulness of the Indians, she includes without comment an account of white travellers leaving behind them packages of strychnine-soaked biscuits for the Indians to find.

Next page