Poet, novelist, and critic Gerald Vizenor is arguably the most accomplished and prolific intellectual in the field of Native American studies.... Vizenors crucial and liberating theories on Survivance, natural reason, the Postindian, and other matters are highly influential in the field.... The world needs more independent minds of Vizenors caliber.

Michael Snyder, Great Plains Quarterly

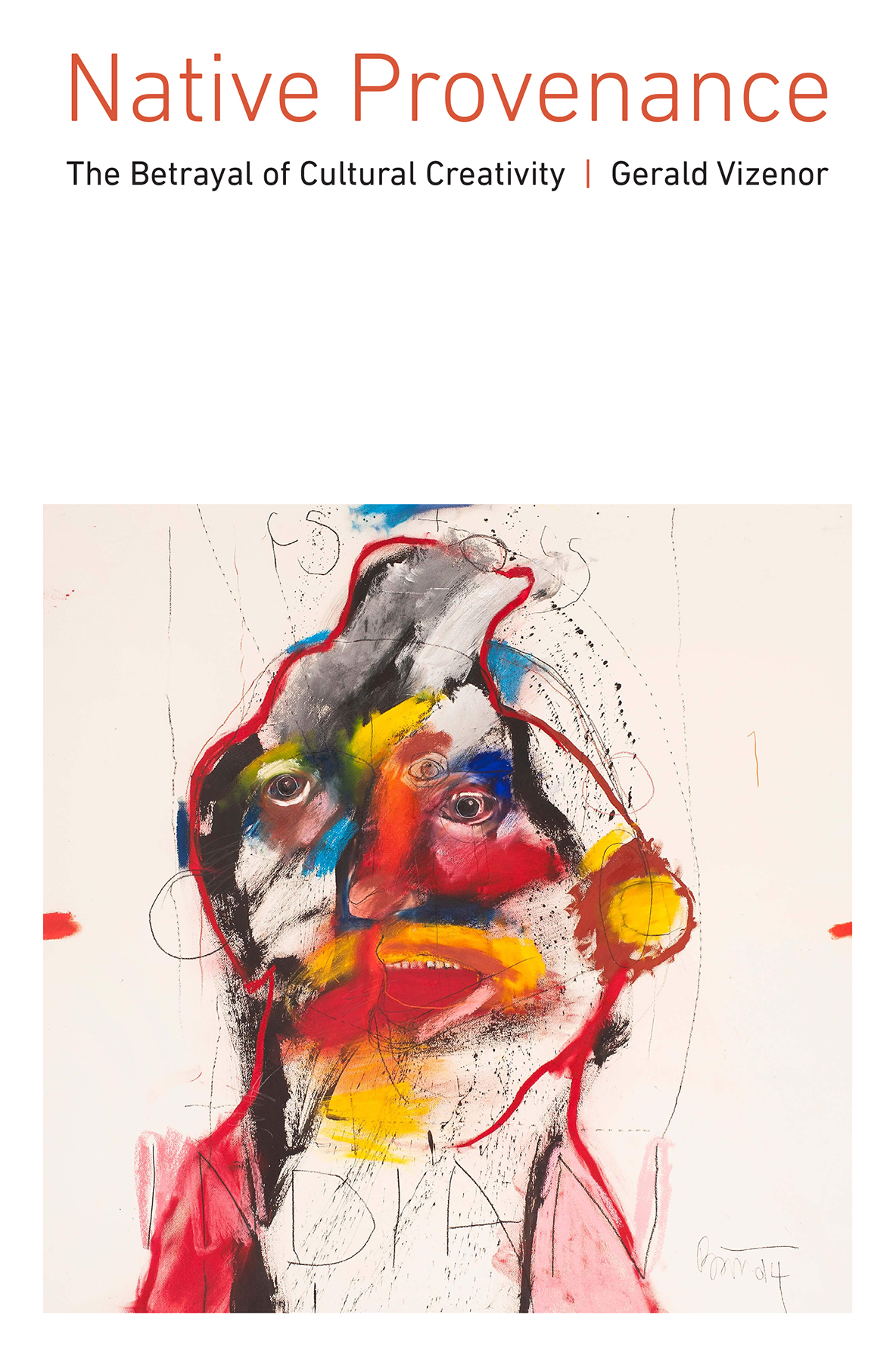

Native Provenance

The Betrayal of Cultural Creativity

Gerald Vizenor

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln

2019 by Gerald Vizenor

Acknowledgments for the use of copyrighted material appear in , which constitutes an extension of the copyright page.

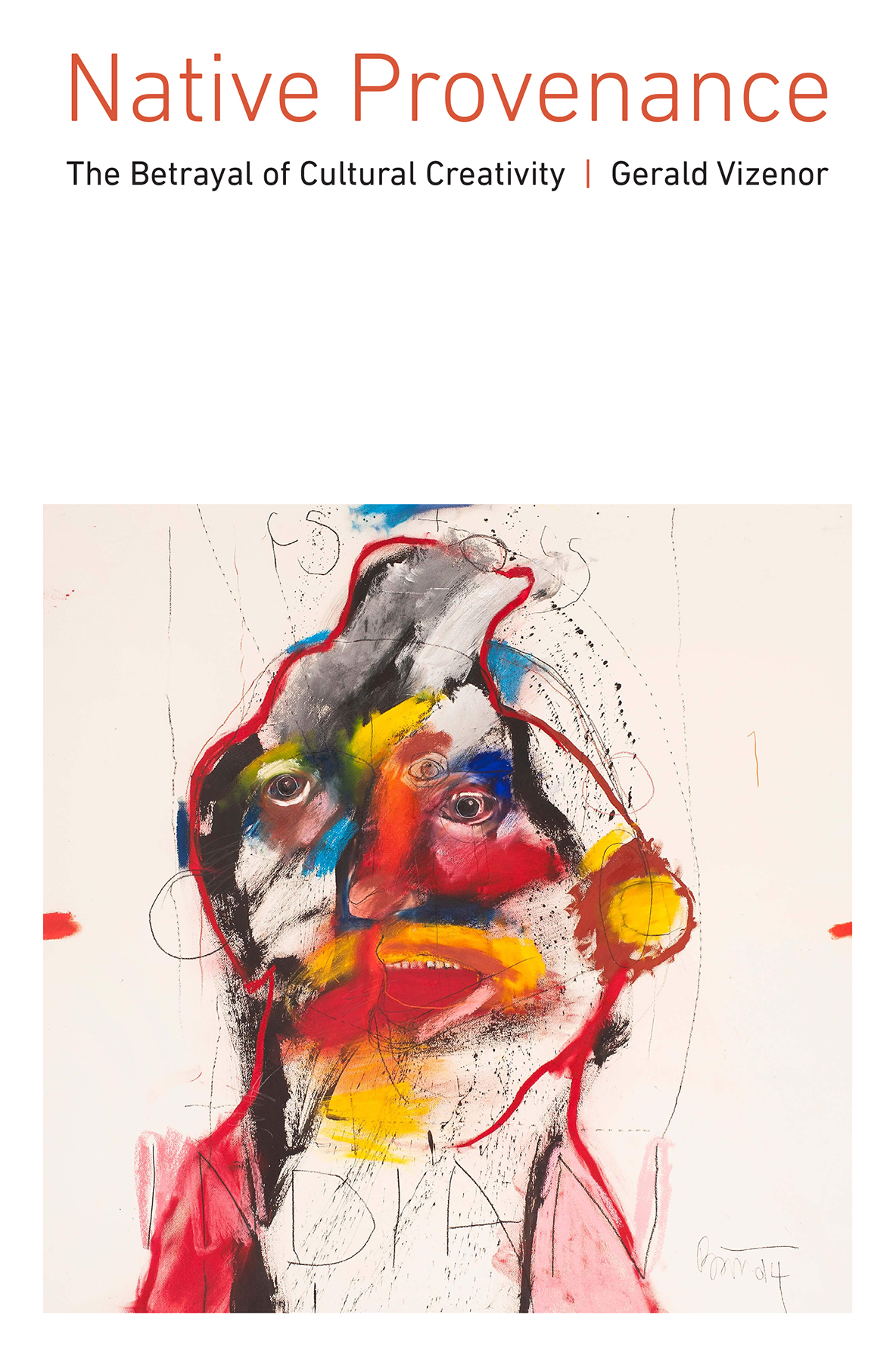

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image: CS Indian by Rick Bartow, 2014, pastel, tempura, graphite on paper, 44.5" x 44.5". Artwork courtesy of the Richard E. Bartow Estate and Froelick Gallery, Portland OR . Photo credit: Rebekah Johnson.

Author photo Laura Hall.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019005333

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Contents

Gossip Theory

Native Irony and the Betrayal of Earthdivers

Native American Indians and Jews are the unmissable monitors of gossip theory, sorts of separatism, and cultural survivance. Natives were once boldly nominated in churchy hearsay as the descendants of the Lost Tribes of Israel. Jews and natives were revealed as an ancestral union of tradition and torment, removal and murder, the outsiders in colonial discoveries, crusades, and crude missions of Christianity.

Thomas Thorowgood proclaimed in Jewes in America, or Probabilities That the Americans Are Jewes that the Indians do themselves relate things of their Ancestors, suteable to what we read of the Jewes in the Bible, and elsewhere.... The rites, fashions, ceremonies, and opinions of the Americans are in many ways agreeable to the custome of the Jewes, not onely prophane and common usages, but such as be called solemn and sacred.

Hallelujah for the suitable and the sacred, and three centuries later the disparate gossip theory of a spiritual and cultural union continues, but with a greater potentiality for survivance stories and a sense of ancestral unintended irony.

Native creation stories were protean, and the tease and weave of ironic gestures were badly translated by pioneers, missionaries, federal agents, and scholars. The conceits of these presiding renditions of creation and race linger in familiar conversations as the betrayal of native imagination and liberty. More than two centuries of sorry betrayal have converted some native stories into the uneasy sentiments of victimry. Yet the nostalgia of kitschy victimry can easily be rescripted with more ironic native stories of resistance and survivance.

Native earthdiver stories were totemic, a creative union of storiers, revelers, and later readers, and rightly the stories of risky escapades were never the same. The trickster created a new earth with teases and stories, and the creation was irony, not liturgy. The essence of an oral creation story was not absolute but deferred, and with respect to the tease and creative vision of another native storier. The ethnographic masters forever revise the methods and models of cultural interpretations, and the outcome of research is reported and compared in abstracts, but there are no federal, academic, or monotheistic contracts to bear or break in the creative stories of native ethos, resistance, and survivance over common gossip theory and victimry.

Avishai Margalit declares in On Betrayal that a thick relation is an element of betrayal. For betrayal, the harm and the offence must take place between people who are presumed to stand in thick relations, and thick relations, whether national or personal, are based on a shared past, that it to say, on shared memory. Federal agents and interpreters of native stories were more rangy than thick, and the gossip theories of totemic and cultural relations were undermined by reservation policies of separatism. Surely moral courage and perceptions of irony are better stands for interpretation.

Clarke Chambers, late professor of history at the University of Minnesota, kindly invited me as a new faculty member in American Indian Studies to dinner at his home. He escorted me to a side room and handed over a pair of stained leather moccasins. The historian was serious and expected me to convey the name of the culture and provide some footsy provenance of a surly warrior. The warrior walked silently in the forests was my first ironic tease, but the historian was focused more directly on the ethnographic features of the sacred footwear than the tease of an ironic provenance.

I closely examined the beaded decorations, blue beads, first acquired in the ancient fur trade with the French. Deer hide, and the soles were soft and thin, more worn around the house than on game runs in the forest. I then sniffed each moccasin and handed them back to the historian. My voice was resonant, of course, suitable for a discourse on the irony of the outworn moccasins: Norwegian man, stinky feet, and he walked with a twisted foot.

Dissembler and simulated ignorance are the original sources of the meaning of irony, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. More precisely, irony is defined as the expression of meaning using language that normally expresses the opposite, especially the humorous or sarcastic use of praise to imply condemnation or contempt. Figuratively, irony is the discrepancy between the expected and actual state of affairs and the use of language with one meaning for a privileged audience and another for those addressed or concerned and those excluded in certain cultural situations.

The potentiality of native irony could be observed more critically as a condition embedded in the notes of discovery, in the documents and narratives of dominion, historical archives, ethnographic monographs, the fickle politics of blood quantum, and in the scenes that were once told and translated as traditional stories. These specific sources of irony are actually inside, at the very heart of the narratives, at the core of monographs and archives of native discovery, and not a coy imposition or outsource of irony.

Native stories, creation and otherwise, were seldom delivered as a catechism or liturgy. The many translations and transcriptions of native songs and stories established an archive of disparate narratives, and so many ethnographic interpretations undermined the creative irony and cultural traces of oral stories.

The ethnographic interpretations, however, now provide an unintended source of native irony. Clearly the irony is embedded, and only rarely implied, in the actual methods of transcription, in the general notions of structural analyses, thick or thin descriptions, and in the heavy sway of academic advisors and editors of monographs.

The moccasin game song about bad moccasins, for instance, was translated and misinterpreted as the lament of a poor native, and with unintended irony. The gestures in the moccasin game songs were about the chance of losing the game, unlucky, not about poverty. The translation of the song must now be delivered as an irony.

The translated song or love charm by a native woman who said she was as beautiful as the roses was actually an ironic song created by a native woman who understood she was not beautiful. Frances Densmore noted in Chippewa Music

Next page