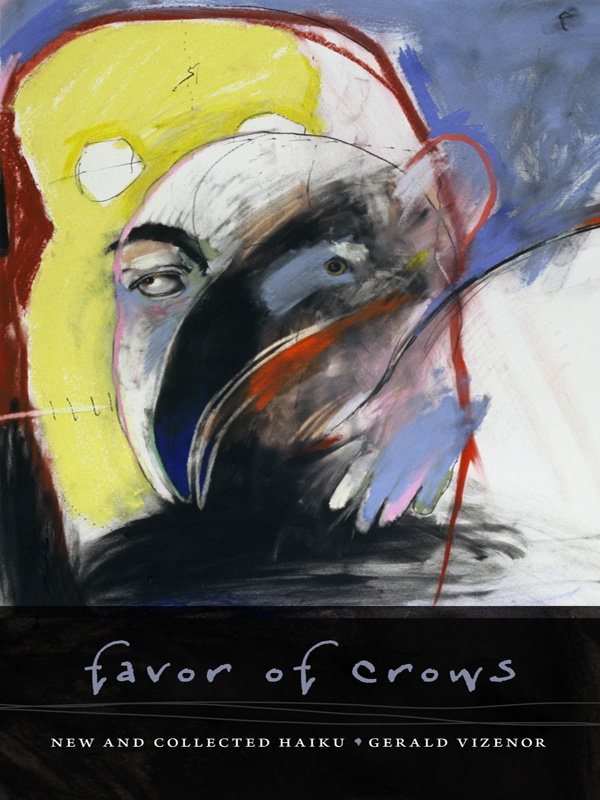

NEW AND COLLECTED HAIKU Gerald Vizenor

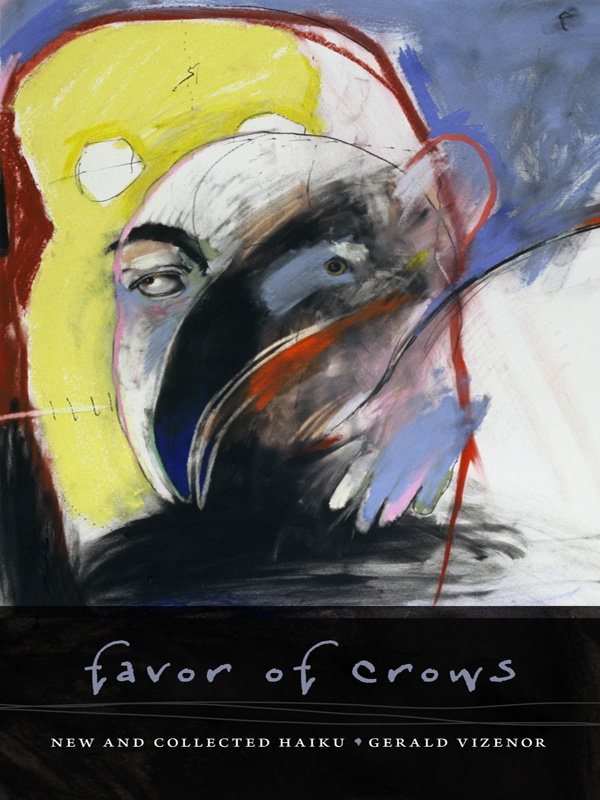

Wesleyan University PressMiddletown, Connecticut WESLEYAN POETRY Wesleyan University Press Middletown CT 06459 www.wesleyan.edu/wespress 2014, 1999, 1984, 1964, Gerald Vizenor All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in 11pt Arno Pro Wesleyan University Press is a member of the Green Press Initiative. The paper used in this book meets their minimum requirement for recycled paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Vizenor, Gerald Robert, 1934 [Poems. Selections] Favor of Crows : New and Collected Haiku / Gerald Vizenor. pages cm.(Wesleyan Poetry series) ISBN 978-0-8195-7432-9 (cloth : alk. Title. Title.

PS3572.I9F39 2014 811'.54 dc23 2013037645 5 4 3 2 1 The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge the illustrations by Robert Houle. Cover illustration by Rick Bartow, Crows Mortality Tale, pastel on paper, 2001. Courtesy of the artist and Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR. In Memory of Six Poets and Teachers Matsuo Bash, Yosa Buson, Kobayashi Issa Ezra Pound, Eda Lou Walton, Edward Copeland  The apparition of these faces in the crowd;Petals on a wet, black bough. In a Station of the Metro, Ezra Pound

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;Petals on a wet, black bough. In a Station of the Metro, Ezra Pound  I would be free of you, my body;Free of you, too, my little soul. Beyond Sorrow, Eda Lou Walton

I would be free of you, my body;Free of you, too, my little soul. Beyond Sorrow, Eda Lou Walton  The first to comeI am calledAmong the birds.I bring the rainCrow is my name Song of the Crows, Henry Selkirk

The first to comeI am calledAmong the birds.I bring the rainCrow is my name Song of the Crows, Henry Selkirk

AN INTRODUCTION

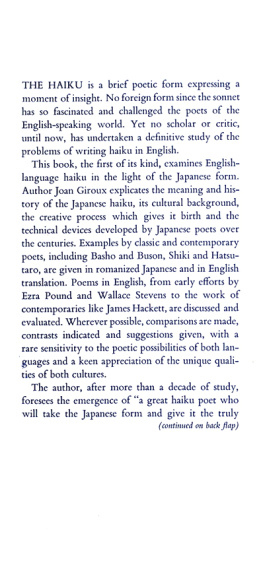

The heart of haiku is a tease of nature, a concise, intuitive, and original moment. Haiku is visionary, a timely meditation, an ironic manner of creation, and a sense of motion, and, at the same time, a consciousness of seasonal impermanence. Haiku scenes are tricky fusions of emotion, ethos, and a sense of survivance. The aesthetic creases, or precise, perceptive turns, traces, and cut of words in haiku, are the stray shadows of nature in reverie and memory.

The original moments in haiku scenes are virtual, the fugitive turns and transitions of the seasons, an interior perception of motion, and that continuous sense of presence and protean nature. Haiku was my first sense of totemic survivance in poetry, the visual and imagistic associations of nature, and of perception and experience. The metaphors in my initial haiku scenes were teases of nature and memory. The traces of my imagistic names cut to the seasons, not to mere imitation, or the cosmopolitan representations and ruminations of an image in a mirror of nature. PINE ISLANDS Matsushima, by chance of the military, was my first connection with haiku images and scenes, the actual places the moon rose over those beautiful pine islands in the haibun, or prose haiku, of Matsuo Bash. Much praise had already been lavished upon the wonders of the islands of Matsushima, Bash writes in The Narrow Road to the Deep North, translated by Nobuyuki Yuasa.

Yet if further praise is possible, I would like to say that here is the most beautiful spot in the whole country of Japan. The islands are situated in a bay about three miles wide in every direction and open to the sea. Islands are piled above islands, and islands are joined to islands, so that they look exactly like parents caressing their children or walking with them arm in arm. The pines are of the freshest green, and their branches are curved in exquisite lines, bent by the wind constantly blowing through them. Matsushima and the pine islands are forever in my memories and in the book. water striders

master bash wades near shore

out of reach The United States Army, by chance, sent me to serve first in a tank battalion on Hokkaido and later at a military post near Sendai in northern Japan. water striders

master bash wades near shore

out of reach The United States Army, by chance, sent me to serve first in a tank battalion on Hokkaido and later at a military post near Sendai in northern Japan.

I was eighteen years old at the time. Haiku, in a sense, inspired me on the road as a soldier in another culture and gently turned me back to the seasons, back to the traces of nature and the tease of native reason and memories. The imagistic scenes of haiku were neither exotic nor obscure to me. Nature then and now was a sense of presence, changeable and chancy, not some courtly tenure of experience, or pretense of comparative and taxonomic discovery. Haiku scenes are similar, in a sense, to the original dream songs and visionary images of the anishinaabe, the Chippewa or Ojibwe, on the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota. I was inspired by these imagistic literary connections at the time.

The associations seem so natural to me now. Once, words and worlds apart in time and place, these poetic images of haiku and dream songs came together more by chance than fate, and later by intuition and consideration. Many anishinaabe dream songs are about the presence of animals, birds, and other totemic creatures in experience, visions, and in memory. The same can be said about haiku scenes, that the visions of nature are the perceptions and traces of memory. Yosa Buson wrote haiku scenes that suggested a longing for home. in matsushima

a man gazing at the moon

empty seashells There, at Matsushima, Bash was so overwhelmed by the moonlit scenery that he was not able to compose observed Ueda. in matsushima

a man gazing at the moon

empty seashells There, at Matsushima, Bash was so overwhelmed by the moonlit scenery that he was not able to compose observed Ueda.

The moon view in Busons hokku may well be Bash, who became empty like a pair of seashells on the shore and could not write. Or the man may represent all visitors to Matsushima, Buson himself included, who are too dazzled by its scenic beauty to find words to express it. And those speechless admirers are numberless like seashells on the shore of Matsushima. The poetic forms of waka,tanka,haikai no renga,hokku, and haiku are interrelated by artistic entitlement, manner, means, and practice in the literary history of Japan. Waka, for instance, a classical form of poetry, is related to tanka, a five-line poem of thirty-one sounds or syllables. The first and third lines are five syllables, and the second, fourth, and fifth lines are each seven syllables.

Tanka poems were included in the Kojiki, the oldest collection of literary narratives, and in the great Manysh, the oldest collection of poetry. These two anthologies were compiled in the eighth century in Japan. Haikai no renga is the customary style of linked seventeen syllable poems. Hokku is the name of the first poem or scene in the series, and later the distinction became a haiku scene. Renga or the creation of linked images was a significant literary practice in the early literature of Japan. Renga is important because it is the origin of haiku, and because it continued to be composed for the next eight hundred years, side by side with the later haiku.

Next page

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;Petals on a wet, black bough. In a Station of the Metro, Ezra Pound

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;Petals on a wet, black bough. In a Station of the Metro, Ezra Pound