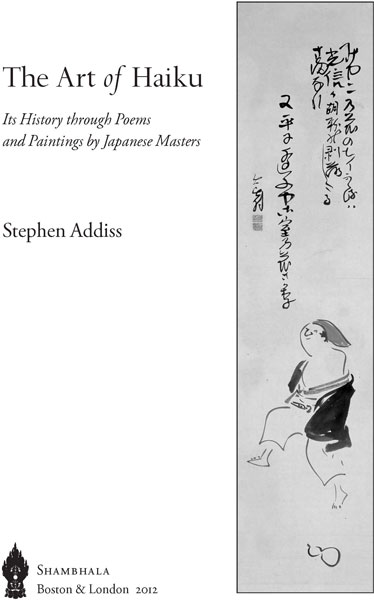

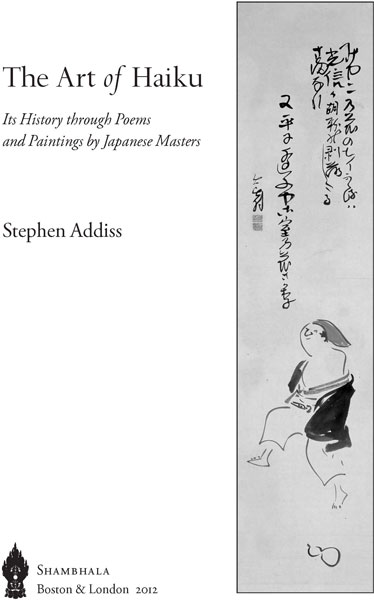

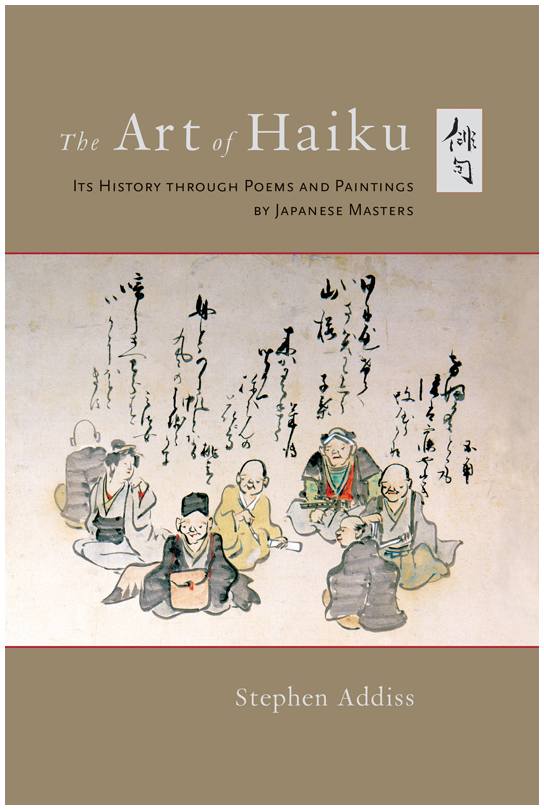

ABOUT THE BOOKIn this in-depth look at the history of haiku and haiku paintings, one of the foremost experts on the art form offers a fascinating discussion on the development of the poetic form, concentrating on the great haiku poets like Basho, Buson, and Issa, but also moving into the twentieth century with poets like Santoka. While much has been written about haiku as a poetic form, haiku paintings, called

haiga, are less widely discussed. Historically, all the leading masters created paintings, or at least calligraphy, with their haiku. The interaction of text and image adds another dimension to the already popular form of haiku, and is especially interesting since the two are so closely interwoven. This thorough history of haiku offers a clear view of the art of haiku and haiku paintings, and is presented with a wealth of examples of poems and paintings.STEPHEN ADDISS, PhD, is Professor of Art at the University of Richmond in Virginia. A scholar-artist, he has exhibited his ink paintings and calligraphy in Asia, Europe, and the United States. He is also the author or coauthor of more than thirty books and catalogues about East Asian arts, including

77 Dances: Japanese Calligraphy by Poets, Monks, and Scholars, 1568-1868.Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

2012 by Stephen Addiss

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Addiss, Stephen, 1935

The art of haiku: its history through poems and paintings by Japanese masters / Stephen Addiss.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2798-1

ISBN 978-1-59030-886-8 (hardcover: acid-free paper)

1. HaikuHistory and criticism. 2. Art and literature

Japan. I. Title.

PL729.A34 2012

809.141dc23

2011046656

To Audrey Yoshiko Seo

Contents

Unless otherwise noted, the translations of the 997 poems in this book are by the author, who bears responsibility for any mistakes or misinterpretations, while acknowledging that haiku often contain more than one meaning. The appendix offers some comments on the difficulties of translating from Japanese to English, and readers are welcome to make their own versions of the poems using the Japanese romanizations supplied with each tanka and haiku.

Also, in this history of haiku and haiga, the ages of poets are given in Japanese style; for example, when Saigy is described as age thirty, we would consider him twenty-nine.

First I must thank Audrey Yoshiko Seo, whose comments, advice, and encouragement have been vital. I would also like to thank Fumiko and Akira Yamamoto, with whom I have worked on previous haiku books, and who continue to be a source of information and wisdom. My great appreciation also goes to Norman Waddell, Joe Seubert, Peter Ujlaki, and my editor, Jennifer Urban-Brown, Ben Gleason, and the entire Shambhala staff.

I must also acknowledge my admiration for those whose work has been so outstanding in the study of traditional Japanese poetry, especially R. H. Blyth, whose many volumes about haiku and senryu fully opened the field to all of us in the West. In addition, I would like to cite Robert H. Brower, Steven Carter, Edwin Cranston, William R. LaFleur, Howard Hibbett, Donald Keene, Earl Miner, Joshua S. Mostow, J. Thomas Rimer, and Arthur Waley for their fine publications on tanka and renga. For exceptional studies of haiku and haiga, I especially admire Robert Aitken, Sam Hamill, David G. Lanoue, Okada Rihei, Sato Hiroaki, Shirane Haruo, John Stevenson, Ueda Makoto, and Burton Watson, among many others. Publications by these scholars and poet-translators are listed in the bibliography, and are highly recommended.

Next I must express my gratitude to all those museums and private collectors who have allowed their works to be published here; their fine haiga deserve to be better known and more fully appreciated in the Western world.

PUBLISHERS NOTE

This book contains Japanese characters and diacritics. If you encounter difficulty displaying these characters, please set your e-reader device to publisher defaults (if available) or to an alternate font.

T HIS BOOK WILL TRACE the history of Japanese haiku, including the poetic traditions from which it was born, primarily through the work of leading masters such as Bash, Buson, Issa, and Shiki, along with a number of other fine poets. Although they are less well-known, haiku calligraphy and haiku-paintings (haiga) of the masters will also be illustrated and discussed as vital elements in the art of haiku. Theory and criticism will be minimized in favor of presenting the works themselves, which were composed to create a spontaneous interconnection with their readers and viewers, who play a vital part in the expressive process.

What Are Haiku?

Although today haiku may be the best-known form of poetry in the world, there is still confusion as to how to define them. Many people would describe haiku as a three-line poem of 575 syllables, but this does not penetrate more than the surface of this remarkable form of poetry. Rather than tight definitions, it might be more useful to discuss the guidelines that most haiku follow.

Haiku in Japan are generally written or printed in a single column. Nevertheless, until the twentieth century, most traditional Japanese examples fall into 575 syllable patterns, although this was stretched and even broken by some of the great masters when it suited their purpose. In the past one hundred years, Japanese haiku poets have been divided between those who basically follow 575, and those who do not. Furthermore, haiku poets in other languages often ignore this guideline. For example, the great majority of fine haiku in English have fewer than seventeen syllables because English is more compact than Japanese, and the same is true of haiku in other languages as well (see the appendix for more information on syllable counts in Japanese and English).

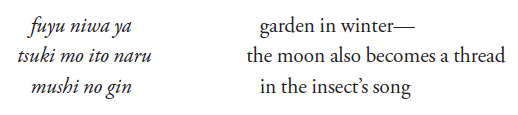

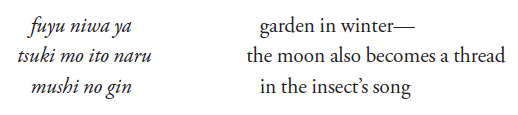

If haiku do not always depend upon a fixed syllable pattern, what are their most important characteristics? One is closeness to nature, which supplies most of the images that the poems rely upon to convey their meanings. This usually involves concrete observations expressed briefly and clearly through the use of everyday language and a syntax that is natural rather than poetic. Since in Japanese language the verb is usually at the end of the sentence, this sometimes involves the translator with changes in word order, but the guidelines remain the same. Here is a view of nature by Bash that finds the extraordinary in the ordinary:

The second characteristic of haiku are references to a particular season; these references are called kigo. In Japanese, the great majority of traditional haiku indicate spring, summer, autumn, or winter, either directly (as in the haiku above) or through images that suggest which season is being presented. Some of these references may seem arbitrary, but they are firmly fixed into haiku history. To give just a few of many possible examples, frogs, swallows, warblers, the hazy moon, late frost, and plum- or cherry-blossoms are all indicators of spring, while for summer there are short nights, herons, toads, lilies, duckweed, and hail. Fall includes the harvest moon, lightning, dew, deer, grasshoppers, dragonflies, and persimmons, while winter is indicated by snow, frost, ice, owls, ducks, fallen leaves, and bare trees. Therefore a Japanese haiku that mentions a frog is understood as a spring poem, while one including a heron is understood as taking place in summer. Since the season adds to the mood and meaning of the poem, these references are significant.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.