HAIKU

HAIKU

AN ANTHOLOGY OF JAPANESE POEMS Stephen Addiss, Fumiko Yamamoto,

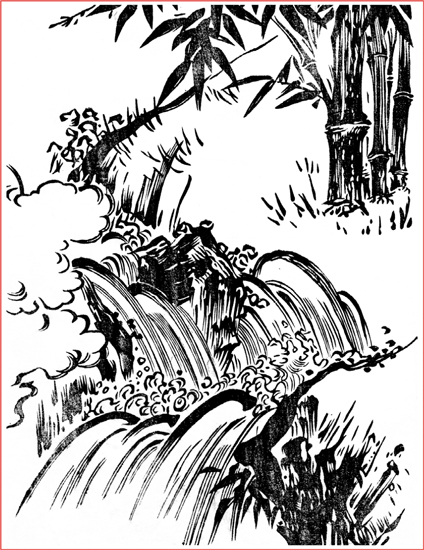

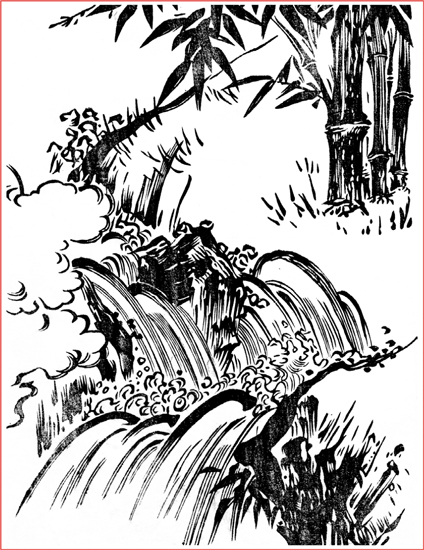

and Akira Yamamoto  SHAMBHALA Boston & London 2011 FRONTISPIECE: Stream, Tachibana Morikuni SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com 2009 by Stephen Addiss, Fumiko Yamamoto, and Akira Yamamoto All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Haiku: an anthology of Japanese poems / [edited by] Stephen Addiss, Fumiko Yamamoto, and Akira Yamamoto.1st ed. p. eISBN 978-0-8348-2234-4 ISBN 978-1-59030-730-4 (acid-free paper) 1. eISBN 978-0-8348-2234-4 ISBN 978-1-59030-730-4 (acid-free paper) 1.

SHAMBHALA Boston & London 2011 FRONTISPIECE: Stream, Tachibana Morikuni SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com 2009 by Stephen Addiss, Fumiko Yamamoto, and Akira Yamamoto All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Haiku: an anthology of Japanese poems / [edited by] Stephen Addiss, Fumiko Yamamoto, and Akira Yamamoto.1st ed. p. eISBN 978-0-8348-2234-4 ISBN 978-1-59030-730-4 (acid-free paper) 1. eISBN 978-0-8348-2234-4 ISBN 978-1-59030-730-4 (acid-free paper) 1.

HaikuTranslations into English. I. Addiss, Stephen, 1935II. Yamamoto, Fumiko Y. III. Yamamoto, Akira Y.

PL782.E3H236 2009 895.6104108dc22 2009010381 CONTENTS H AIKU are now one of the best-known and most practiced forms of poetry in the world. Simple enough to be taught to children, they can also reward a lifetime of study and pursuit. With their evocative explorations of life and nature, they can also exhibit a delightful sense of playfulness and humor. Called haikai until the twentieth century, haiku are usually defined as poems of 5-7-5 syllables with seasonal references. This definition is generally true of Japanese haiku before 1900, but it is less true since then with the development of experimental free-verse haiku and those without reference to season: for example, the poems of Santka (18821940), who was well known for his terse and powerful free verse. Seasonal reference has also been less strict in senry, a comic counterpart of haiku in which human affairs become the focus.

Freedom from syllabic restrictions is especially true for contemporary haiku composed in other languages. The changes are not surprising. English, for example, has a different rhythm from Japanese: English is stress-timed and Japanese syllable-timed. Thus, the same content can be said in fewer syllables in English. Take, for example, the most famous of all haiku, a verse by Bash (164494): Furu ike ya kawazu tobikomu mizu no oto Furu means old, ike means pond or ponds, and ya is an exclamatory particle, something like ah. Kawazu is a frog or frogs; tobikomu, jump in; mizu, water; no, the genitive of; and oto, sound or sounds (Japanese does not usually distinguish singular from plural).

If using the singular, a literal translation would be: Old pond a frog jumps in the sound of water Only the third of these lines matches the 5-7-5 formula, and the other lines would require padding to fit the usual definition: [There is an] old pond [suddenly] a frog jumps in the sound of water This kind of padding tends to destroy the rhythm, simplicity, and clarity of haiku, so translations of 5-7-5syllable Japanese poems are generally rendered with fewer syllables in English. Translators also have to choose whether to use singulars or plurals (such as frog or frogs, pond or ponds, and sound or sounds), while in Japanese these distinctions are nicely indeterminate. We have attempted to offer English translation as close to the Japanese original as possible, line-by-line. Sometimes a parallel English translation succeeds in conveying the sense of the original. This haiku by Issa provides an example: Japanese kasumu hi no (mist day of) uwasa-suru yara (gossip-do maybe) nobe no uma (field of horse)Close Translation Misty day they might be gossiping, horses in the field Sometimes the attempt at a parallel translation results in awkward English, and a freer translation is necessary, as with this haiku by Buson: Japanese yoru no ran (night of orchid) ka ni kakurete ya (scent in hide wonder) hana shiroshi (flower be=white)Close Translation Evening orchid is it hidden in its scent? the white of its flower Freer Translation Evening orchid the white of its flower hidden in its scent Other times a parallel translation doesnt have the impact that can be delivered in a freer translation, as in this haiku by an anonymous poet: Japanese mayoi-go no (lost-child of) ono ga taiko de (ones=own drum with) tazunerare (be=searched=for)Close Translation The lost child with his own drum is searched for Freer Translation Searching for the lost child with his own drum Thus, the challenge for translators is to try to follow the Japanese word and line order without resulting in awkward English. While admirable, sometimes adhering to the original verses may make for weaker poems in English.

Sometimes the languages are too different to make a close match without hurting the flow and even the meaning. However, when closer translations succeed, they are powerfully satisfying. The fact that the spirit of the haiku can be effectively rendered in English translation indicates that the 5-7-5 syllabic count captures the outward rhythmic form of traditional Japanese haiku but does not necessarily define them. The strength of haiku is their ability to suggest and evoke rather than merely to describe. With or without the 5-7-5 formula and seasonal references, readers are invited to place themselves in a poetic mode and to explore nature as their imaginations permit. Returning to Bashs frog, what does the poem actually say? On the surface, not very muchone or more frogs jumping into one or more ponds and making one or more sounds.

Yet this poem has fascinated people for more than three hundred years, and the reason why remains something of a mystery. Is it that it combines old (the pond) and new (the jumping)? A long time span and immediacy? Sight and sound? Serenity and the surprise of breaking it? Our ability to harmonize with the nature? All of these may evoke an experience that we can share in our own imaginations. Whatever meanings it brings forth in readers, this haiku has not only been appreciated but also variously modeled after and sometimes even parodied in Japan, the latter suggesting that readers should not take it too seriously. To give a few examples, the Chinese-style poet-painter Kameda Bsai (17521826) wrote: Old pond after that time no frog jumps in while the Zen master Sengai Gibon (17501837) added new versions: Old pond something has PLOP just jumped in Old pond Bash jumps in the sound of water Bash has become so famous for his haiku that this eighteenth-century senry mocks the now self-conscious master himself: Master Bash, at every plop stops walking In the modern world, new transformations of this poem keep appearing even across the ocean, including this haiku with an environmental undertone by Stephen Addiss: Old pond paved over into a parking lot one frog still singing Perhaps one reason why haiku have become internationally popular in recent decades comes from our sensitivity to our surroundings, even to the development of towns and cities, often to the detriment of the natural world: poets have power to keep on singing the connection to nature in their new milieu. Haiku in Japan Although haiku is now a worldwide phenomenon, its roots stretch far back into Japans history. The form itself began with poets sharing the composition of linked verse in the form of a series of five-line

Next page

HAIKU

HAIKU

SHAMBHALA Boston & London 2011 FRONTISPIECE: Stream, Tachibana Morikuni SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com 2009 by Stephen Addiss, Fumiko Yamamoto, and Akira Yamamoto All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Haiku: an anthology of Japanese poems / [edited by] Stephen Addiss, Fumiko Yamamoto, and Akira Yamamoto.1st ed. p. eISBN 978-0-8348-2234-4 ISBN 978-1-59030-730-4 (acid-free paper) 1. eISBN 978-0-8348-2234-4 ISBN 978-1-59030-730-4 (acid-free paper) 1.

SHAMBHALA Boston & London 2011 FRONTISPIECE: Stream, Tachibana Morikuni SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com 2009 by Stephen Addiss, Fumiko Yamamoto, and Akira Yamamoto All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Haiku: an anthology of Japanese poems / [edited by] Stephen Addiss, Fumiko Yamamoto, and Akira Yamamoto.1st ed. p. eISBN 978-0-8348-2234-4 ISBN 978-1-59030-730-4 (acid-free paper) 1. eISBN 978-0-8348-2234-4 ISBN 978-1-59030-730-4 (acid-free paper) 1.