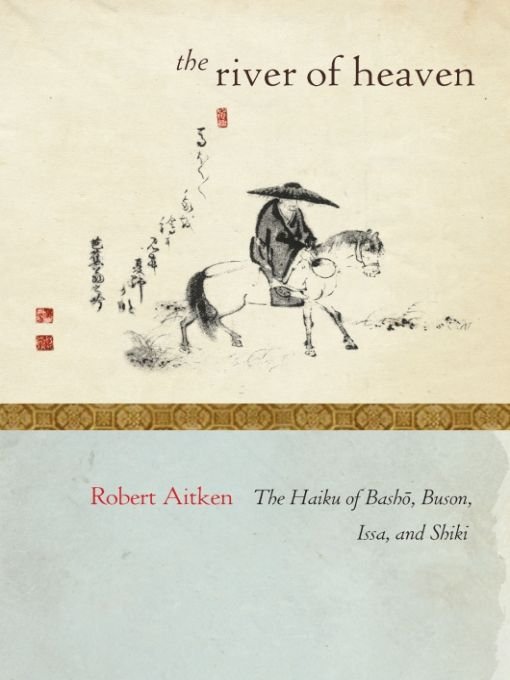

Table of Contents

ALSO BY ROBERT AITKEN

Miniatures of a Zen Master

The Morning Star

Zen Master Raven

Original Dwelling Place

The Dragon Who Never Sleeps

The Practice of Perfection

Encouraging Words

The Gateless Barrier

The Mind of Clover

Taking the Path of Zen

A Zen Wave

with David Steindl-Rast,

The Ground We Share

with Daniel W. Y. Kwok,

Vegetable Roots Discourse

For Amy and Stephanie

Load every rift with ore.

John Keats

Recollection of Robert Aitken

BY SUSAN MOON

WHEN AITKEN ROSHI was seventy-nine, he stepped down from being head teacher of the Diamond Sangha and passed the reins on to his dharma heir, Nelson Foster. I was lucky to go to the stepping-down ceremony at the Plolo temple on Oahu, along with Alan Senauke, to represent Buddhist Peace Fellowship.

The grand occasion included a shosan ceremony, in which Roshi sat in a ceremonial chair and visitors asked him questions about the dharma. In the only exchange I still remember, someone asked him: What is the most precious thing? and he replied, A good nights sleep.

I was moved by this intimate and humble answer. Yes, I thought, he must be tired sometimeshe works so hard as a teacher and a writer.

One of my favorites of Robert Aitkens books is

The Dragon Who Never Sleeps, a collection of his

gathas, or short verses, for practicing mindfulness in everyday life. His vows drop onto the pages like petals. He writes:

Falling asleep at last

I vow with all beings

to enjoy the dark and the silence

and rest in the vast unknown.

Have a good nights sleep, dear Roshi.

The Summer Moor

Matsuo Bash

BASH WAS BORN Matsuo Kinsaku in Iga-Ueno, just north of Kyoto, in 1644. His father died in 1656, when he was twelve, and probably by this time he had entered the service of Td Yoshida, the young son of the feudal lord who ruled the area. He wrote his first recorded haiku when he was eighteen and gave himself the pen name Tsei. Yoshida died in 1666, and Bash, overcome by grief, was unsettled for a long time, though by 1680 he had a full-time job teaching the writing of haiku and had twenty devoted disciples, who published The Best Poems of Tseis Twenty Disciples.

He then moved to Edo and on, across the river to Fukagawa, for a reclusive life out of the public eye. His disciples built him a rustic hut and planted a banana tree (bash) in the yard, giving him a new pen name and his first permanent home. Later on, probably for career purposes, he moved back to Edo, where he had another Bash hermitage, and yet another. (I am reminded of my Zen master Yasutani Hakun, who moved from one rental unit to another in Tokyo and moved the name he had given his first little house, Taihei An, Great Peace Hermitage, to his next rental along with his robes and bowls.)

Despite his successes in Edo, Bash felt dissatisfied and lonely. He began to practice zazen with the master Butch Osh, but it seems not to have calmed his mind. I think it is possible to attribute those feelings of depression to the beginnings of a stomach ailment, possibly cancer.

In the spring of 1684, Bashs mother died, and he visited his old home in Iga-Ueno to wind up her affairs and deal with her belongings. There he had the most poignant discovery imaginable. He wrote:

furusato ya / heso no o ni naku / toshi no kure

At my native village

I wept over my umbilical cord

first rains of spring.

That same year his disciple Takarai Kikaku published a compilation of Bashs poems and those of other poets as

Shriveled Chestnuts. The poet then went on the first of four major wanderings. He was born to travel, and he wrote at the outset of one journey he memorialized as

The Record of a Travel-Worn Satchel:

tabibito to / waga na yobaren / hatsu shigure

Let my name

be Traveler

first rains of spring.

Traveling in medieval Japan was immensely dangerous, and at first Bash expected to simply die in the middle of nowhere or be killed by bandits. In spite of this fearsome danger, he enjoyed the changing scenery and the seasons. He met several poets in villages and towns along the way who called themselves his disciples and wanted his advice, and he told them to disregard the contemporary Edo style and even his own Shriveled Chestnuts, saying it contained many verses that are not worth discussing.

When Bash returned to Edo after his first trip, he resumed his job as a teacher of poetry, though privately he was already making plans for other journeys. In early 1686 he composed a haiku that marked a transformative experience, an experience that made him the poet we remember:

furu ike ya / kawazu tobikomu / mizu no oto

An old pond;

a frog leaps in

the water sound.

Many scholars simply enter this verse without comment as just one among many that Bash composed in 1686, but it is not simply one among many. It stands out as one that brings the leap and the sound together, and the sound of the water together with its onomatopoeic presentation, oto. With the experience of writing this verse came Bashs insight into the way many different dimensions can complement each otherpast and present, near and far, color and sound, and so on. Mere imagery was something he left behind forever.

Finally Bash set about planning for a long journey to the northern provinces of Honsh, and in May 1689, he left Edo with his disciple Kawai Sora. They headed north to Hiraizumi, on the east side of the island, which they reached in late June. They then walked to the west side, detouring to see the island of Kisata at the northern end of Honsh on July 30, and began hiking back home at a leisurely pace along the coastline. Bash reached the peak of creativity during this journey and wrote many of his finest verses in the course of his sightseeing and encounters with many people who interested him.

During his 150-day journey, Bash traveled a total of 400 kilometers. He kept a diary of his trip, which he called The Narrow Way Within (Oku no Hosomichi). He finally completed editing the diary the year he died. The first edition of this work was published posthumously in 1702. It was an immediate commercial success, and many other itinerant poets followed the path of his journey.

Toward the end of his life, Bash wrote to a friend that he was disturbed by others. He shut his gate in August 1693 and refused to see anybody for a month. Finally he relented and left Edo for the last time in the summer of 16 94. He spent time in Iga-Ueno and Kyoto before arriving in Osaka, where he suffered an attack of his old stomach ailment and died peacefully, surrounded by his disciples.

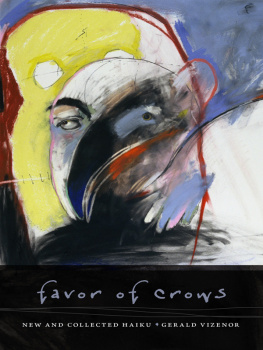

CROW AT EVENING

kare eda ni / karasu no tomari keri / aki no kure

On a withered branch

a crow is perched

an autumn evening.