THE WINTER SUN SHINES IN

ASIA PERSPECTIVES: HISTORY, SOCIETY, AND CULTURE

Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University

ASIA PERSPECTIVES: HISTORY, SOCIETY, AND CULTURE

A series of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University

Carol Gluck, Editor

Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery in the Japanese Military During World War II, by Yoshimi Yoshiaki, trans. Suzanne OBrien

The World Turned Upside Down: Medieval Japanese Society, by Pierre Franois Souyri, trans. Kathe Roth

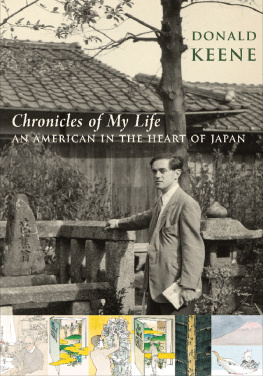

Yoshimasa and the Silver Pavilion: The Creation of the Soul of Japan, by Donald Keene

Geisha, Harlot, Strangler, Star: The Story of a Woman, Sex, and Moral Values in Modern Japan, by William Johnston

Lhasa: Streets with Memories, by Robert Barnett

Frog in the Well: Portraits of Japan by Watanabe Kazan, 1793 1841, by Donald Keene

The Modern Murasaki: Writing by Women of Meiji Japan,

edited and translated by Rebecca L. Copeland and Melek Ortabasi

So Lovely a Country Will Never Perish: Wartime Diaries of Japanese Writers, by Donald Keene

Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Nippon: A Geopolitical Prehistory of J-Pop, by Michael K. Bourdaghs

DONALD KEENE

THE WINTER SUN SHINES IN

A LIFE OF MASAOKA SHIKI

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2013 Donald Keene

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53531-1

Library of Congres

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Keene, Donald.

The winter sun shines in : a life of Masaoka Shiki / Donald Keene.

pages cm. (Asia Perspectives: History, Society, and Culture)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16488-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-53531-1 (e-book)

1. Masaoka, Shiki, 18671902. I. Title.

PL811.A83Z6776 2013

895.6'14dc23

[B]

2012048137

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

BOOK & COVER DESIGN BY CHANG JAE LEE

Photographs and images in the insert courtesy of the Shiki Museum.

For Lindsley Miyoshi,

who enabled me to become a Japanese

CONTENTS

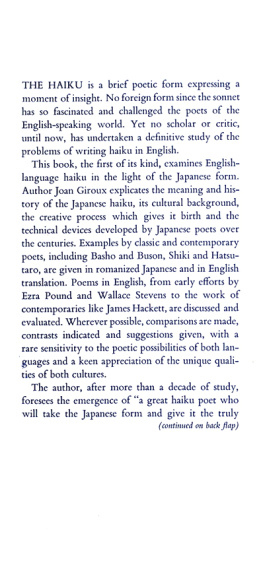

I n 1867, the year that Masaoka Shiki was born, Japanese literature was at one of its lowest points. The quality of all varieties of literature had steadily declined, though readers were not necessarily aware of this unfortunate change. A half dozen writers, all that were left of the group of novelists who had flourished half a century earlier, provided readers with endless variations on the plots of old stories. On the surface, it might seem that poetry was thriving. Many self-appointed masters of the haiku made a living by correcting poems written by disciples and by transmitting to them (in return for suitable fees) the secrets of composing haiku in the style of Bash. A very large number of haiku were turned out by such teachers and disciples, but not a single poem of this period is remembered today except by specialists. A similar situation prevailed among poets of the tanka, the other major poetic form.

The dismal condition in poetry was saved by one man, Masaoka Shiki, whose poetry and criticism of poetry, at first known mainly in the provincial town of Matsuyama, before long were read and imitated in all parts of the country. Matsuyama was a strange place for a literary revolution to begin. As Shiki himself admitted, nothing of literary importance had ever been written in the town or fiefdom, though it was not totally without culture. There were in fact local poets of haiku and tanka who gave Shiki, still a young man, rudimentary instruction in poetic composition, but nothing they taught him would be of use when he initiated his revolution in poetry.

Shikis first poems were probably composed in classical Chinese as part of his basic education. At the school he attended, for boys of the samurai class, he was required to compose poetry in Chinese, rather as students at many European schools were expected to compose poetry in Latin, mainly as a duty of persons belonging to a superior class. During the rest of his life Shiki would continue to write poems in Chinese, generally when he wished to express observations or sentiments that did not easily fit into the seventeen syllables of a haiku or the thirty-one syllables of a tanka.

Shiki did not begin to compose haiku until he was in his early twenties. A haiku composed in the summer of 1891 (when he was twenty-four) is notable not only for its sensitivity to nature and the seasons, typical of Japanese poetry, but also for its unusual combination of imagery:

| ajisai ya | Hydrangeas |

| kabe no kuzure wo | and rain beating down |

| shibuku ame | on a crumbled wall |

The rain gives the hydrangeas their fresh beauty but at the same time beats down mercilessly on the dead wall. Other poems of interest are scattered among Shikis early haiku, but most of the haiku for which he is known today were composed later on, after he had developed his characteristic style, known as shasei (sketching from nature).

The ideal of shasei as found in Shikis haiku owed much to Nakamura Fusetsu, a mediocre painter who, after studying European paintings, had reached the conclusion that art of any kind must faithfully reflect whatever it portrays. This variety of realism contrasted markedly with the ideals of Japanese painters of the time, who made it their practice to imitate closely the works of their teachers, painting the same poetic landscapes, not feeling any need to discover fresh scenes or viewpoints of their own. The paintings they producedmountains in the mist, men crossing flimsy bridges over gorges, and so onwere pleasing to the eye but lacked both originality and fidelity to any actual landscape. During the discussions between Shiki and Fusetsu that began soon after they met in 1895, Shiki at first defended traditional Japanese painting, preferring its artistry to European realism; but Fusetsu eventually convinced Shiki that shasei was essential not only in painting but in the haiku. Once convinced, Shiki made up his mind that his haiku would treat the experiences of daily life, and he turned his back on cherry blossoms and colored autumn leaves, the hackneyed subjects of Japanese poetry. He would write instead about what he himself had seen or felt, regardless of whether or not it was conventionally beautiful.

Although Shiki was determined to write in a style unlike that of his predecessors, he was by no means indifferent to their poetry. For years he poured over old books of haiku, classifying each of them and searching for anything that might benefit his own poetry. He insisted that his disciples also study the history of the haiku no less diligently than himself. When his most trusted disciple, Takahama Kyoshi, refused to devote himself single-mindedly to study, Shiki resignedly broke with him.