Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

IDLY SCRIBBLING RHYMERS

Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute

Columbia University

STUDIES OF THE WEATHERHEAD EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

The Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute of Columbia University were inaugurated in 1962 to bring to a wider public the results of significant new research on modern and contemporary East Asia.

Idly Scribbling Rhymers

Poetry, Print, and Community in Nineteenth-Century Japan

Robert Tuck

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press wishes to express its appreciation for assistance given by the Wm. Theodore de Bary Fund in the publication of this book.

Columbia University Press wishes to express its appreciation for assistance given by the Association for Asian Studies toward the cost of publishing this book.

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54722-2

Cataloging-in-Publication Data available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-231-18734-3 (cloth)

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

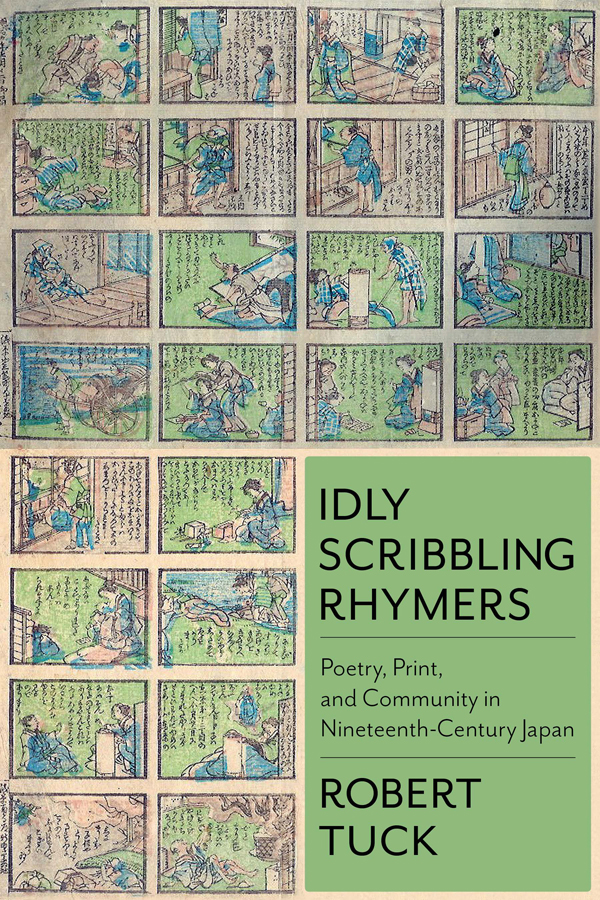

Cover design: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

Cover image: Paul Fearn / Alamy

To Kate

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

Climbing the Stairs of Poetry: Kanshi , Print, and Writership in Nineteenth-Century Japan

CHAPTER TWO

Not the Kind of Poetry Men Write: Fragrant-Style Kanshi and Poetic Masculinity in Meiji Japan

CHAPTER THREE

Clamorous Frogs and Verminous Insects: Nippon and Political Haiku, 18901900

CHAPTER FOUR

Shikis Plebeian Poetry: Haiku as Commoner Literature, 18901900

CHAPTER FIVE

The Unmanly Poetry of Our Times: Shiki, Tekkan, and Waka Reform, 18901900

Many people contributed to this project over the nearly ten years leading up to its publication. Thanks are due first of all to Haruo Shirane, whose guidance, good advice, and unflagging support laid the foundations not only for this book but also for a number of other subsequent projects. Tomi Suzuki pushed me to push myself throughout my time as a graduate student, helped me to develop as a scholar, and provided much useful advice on how to structure the book. David Lurie was always available and eager to bat ideas around and was a never-ending source of encouragement, particularly when I happened to stumble across something cool. Wiebke Denecke, while at Barnard, made me a better reader of kanbun and kanshi and introduced me to a number of both new ideas and people that helped my career immensely. Paul Anderer broadened my horizons in modern Japanese literature and film and trained me to think about texts in ways I had never previously considered.

While at Waseda from 2008 to 2010, Munakata Kazushige and Toeda Hirokazu helped me not only to find my feet in Tokyo but also to make sense of the unwieldy project I had brought to Japan and to take it in a more manageable direction. Fellowship support from the Japan Foundation and from Shinchsha also provided invaluable time and freedom to do the archival work, particularly in terms of Meiji-era newspapers and periodicals, that underpins the book. I extend my sincere thanks to both organizations: the book would not have been possible without their generous support.

In June 2017, the Weatherhead East Asian Institute at Columbia University selected Idly Scribbling Rhymers as a recipient of its First Book Prize, a major honor and real vote of confidence in the project. My thanks to the selection committee and also to Ross Yelsey at the institute for all of his hard work, which helped to make the path to publication immeasurably smoother. I also would like to express my thanks to the Association of Asian Studies for providing subvention support through the AAS First Book Subvention Program.

I have been lucky enough to have a wonderful and supportive set of colleagues at the University of Montana. Judith Rabinovitch was, simply, the best mentor a junior scholar could wish for, helping me to get myself up and running (and to figure out how to teach effectively), and was always willing to chat about kanshi , the tenure track, or life in general. With Tim Bradstock, too, I spent many enjoyable hours discussing innumerable aspects of Chinese and Japanese literature, filling in the (many) gaps in my own understanding. Tim and Judith both took the time to read early drafts of a number of articles and of the chapters of this book; I owe them both a great deal. Brian Dowdle was (and is) a great source of support, good advice, and an all-around wonderful colleague. My new colleagues Michihiro Ama and Eric Schluessel took the time, despite being in their first year at the University of Montana, to read my lengthier chapters and provide insightful comments. I also received grant support for research and travel to Japan from the Yamaguchi Opportunity Fund and University Grants Program at the University of Montana, as well as from the Northeast Asia Council of the Association of Asian Studies, all of which enabled me to gather additional archival materials on a second trip to Japan in 2013.

Many others played important roles. Matthew Fraleigh provided helpful criticism and a second pair of eyes early on, and he continues to be extremely generous with his time and advice. Paul Rouzer read over the Kegon Falls poems and helped point out things I had overlooked. Machi Senjur, Matthew Mewhinney, Ted Mack, and Tom Gaubatz all helped me access vital primary sources when I was unable to go to Japan or lay hands on them myself. I would also like to thank Janine Beichman, Emmanuel Lozerand, and Keith Vincent for support and encouragement throughout the past few years. I also extend my thanks to the two anonymous readers for Columbia University Press, whose careful reading of and perceptive comments on the manuscript improved it beyond measure.

Finally, thanks are due to my family, on both sides of the Atlantic, for their love and belief in me: my mother and father, Amanda and Anthony Tuck, and my brother Mike and his family; and, in the United States, my gratitude to Jack, Victoria, Dan, Joan, Anita, and David. Last, but not least, thanks to my wife, Kate, and to our two children, Alex and Zo, who make life worthwhile.

In February and March of 2006, the haiku poet and critic Fukunaga Norihiro published a two-part piece in the journal Haiku , one that was strikingly pessimistic about what the internet would do foror rather, tohaiku in Japan. Although Fukunaga recognized that the internet offered haiku certain benefits, such as allowing mothers with children, very busy salarymen, and people living overseas to participate in haiku gatherings remotely, he also saw a number of dangers.

Fukunagas piece drew a number of rebuttals. Critic Takayanagi Katsuhiro, writing in the same journal in 2010, noted that advances in coding in the intervening four years had made it easy to write haiku vertically online if one chose.

As Takayanagis invocation of Shiki suggests, the issues with which Fukunaga was concernedliterary quality versus broad participation, concerns over new media technology and the boundaries of literary community, the question of elite versus popular genreswere not new ones in Japanese poetic history. In fact, Fukunagas reflections, in the aftermath of a shift in media technology, on haikus value as a popular genre would not have been out of place in the Meiji era itself; in some ways, they sound remarkably similar to Shikis own writings on the subject. At the root of Fukunagas concerns appears to be a simple question: if anyone can do it, what is the value of being a poet? Or, stated in more concise terms: who can, or should, be a poet?