Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

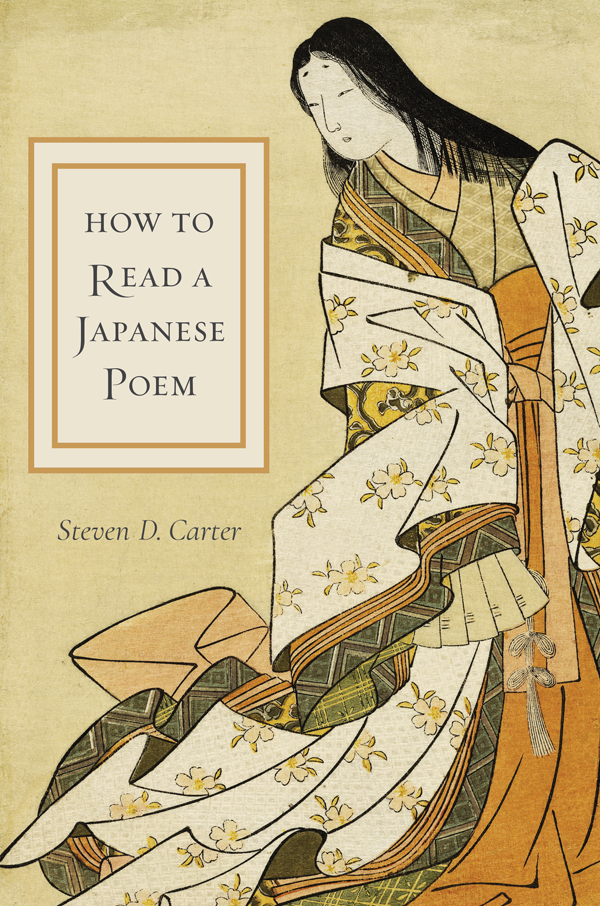

HOW TO READ A JAPANESE POEM

HOW TO READ A JAPANESE POEM

Steven D. Carter

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press gratefully acknowledges the generous support for this book provided by Publishers Circle member Bruno A. Quinson.

Columbia University Press wishes to express its appreciation for assistance given by the Pushkin Fund in the publication of this book.

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2019 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54685-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Carter, Steven D., author.

Title: How to read a Japanese poem / Steven D. Carter.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018032537 (print) | LCCN 2018052344 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231186827 | ISBN 9780231186827 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231186834 (paperback) | ISBN 9780231546850 (electronic)

Subjects: LCSH: Japanese poetryHistory and criticism. | Japanese poetryAppreciation.

Classification: LCC PL727 (ebook) | LCC PL727 .C37 2019 (print) | DDC 895.6109dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018032537

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Lisa Hamm

Cover image: The Trustees of the British Museum. Art attributed to Suzuki Harunobu. 1765 to 1770, Meiwa Era. A portrait of the poetess, Ono no Komachi.

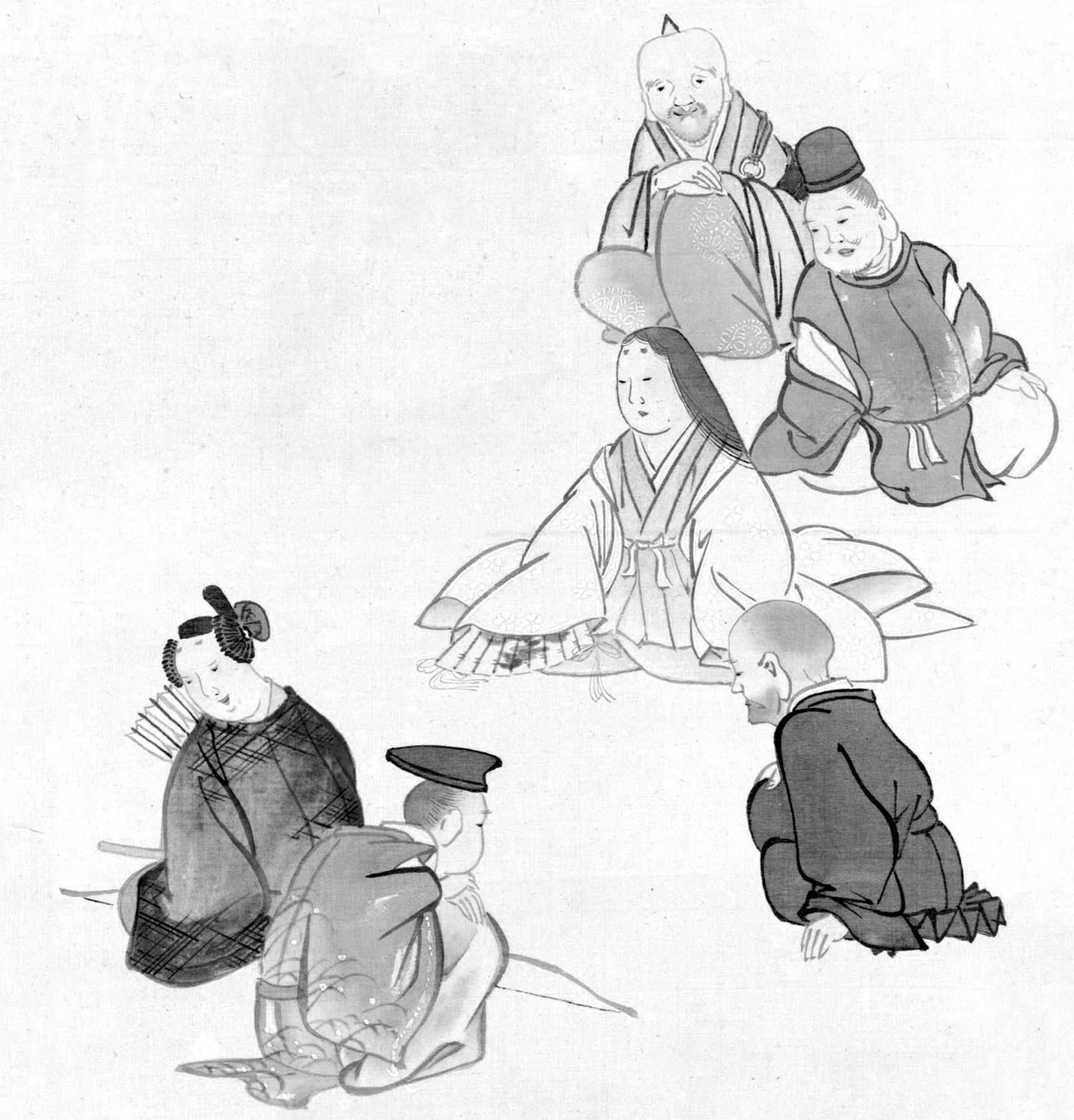

Title page image: Gift of Sebastian Izzard and Masaharu Nagano, in memory of T. Richard Fishbein, 2014. Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Six Immortal Poets , Kubo Shunman (Japanese, 17571820) , and others. Edo Period.

For Caroline and Mia

not coarse, hard

things last

longest, perhaps,

but fine, very fine:

if only the wind

could take letters

from Tombstones by A. R. Ammons

CONTENTS

A s always, I thank my wife, Mary, for her support and good advice, kindly given.

I would like to acknowledge the assistance and inspiration I have received from my many mentors in the study of Japanese poetry over the years, especially Professors Helen Craig McCullough, Kaneko Kinjir, Robert H. Brower, Earl Miner, Edwin Cranston, and Iwasa Miyoko. Also due thanks are the participants in a reading group involving faculty, postdoctoral fellows, and students that I led at Stanford University over a number of years involving Christina Laffin, Rebecca Corbett, LeRon Harrison, Jeffrey Knott, Caroline Akiko Wake, Nancy Hamilton, and Lisa Wilcut. Many of the pages in this book got their first reading on those Friday afternoons, and I gained greatly from the comments and suggestions offered around our table. Any mistakes that remain in the book are of course mine alone.

Two anonymous readers for Columbia University Press made a number of helpful suggestions, for which I am duly grateful. I also thank Jack Stoneman for assistance with illustrations and Christine Dunbar, Leslie Kriesel, Christian Winting, and the whole staff at Columbia University Press for their tireless efforts to shepherd a very complex manuscript through the editing process.

Late Edo-period painting by Kubo Shunman of a woman at a writing desk.

Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art and Marjorie H. Holden Gift, 2012.

P oets asked to define poetry, especially good poetry, often throw up their hands. I can no more define poetry, said A. E. Housman, than a terrier can define a rat. With that in mind, my title, How to Read a Japanese Poem , may seem a bit audacious. How does one dare to tell people how to read poetry if it is hard to even define what poetry is?

So perhaps my project would be better stated as, How to begin to read a Japanese poem. My purpose is not to dictate a destination but to give a few signposts as readers walk the road. This book, then, offers my advice on how to approach Japanese poems in traditional forms, according largely to analytical methods established by Japanese poets, scholars, and critics over the centuries. Obviously there are other ways to approach such a task, but this one seems to me a wise one for beginners.

Each of my seven chapters focuses on separate genres of Japanese poetry and proceeds by analyzing examples in chronological order. In each case, I first give short notes about authorship, along with other details of context, including variously the time of composition, physical setting, social occasion, and textual settingthings to which particular attention has habitually been given by participants in Japanese poetic discourse from the earliest times. Then I move on to a short commentary. My decision to proceed from context to commentary is dictated by a central feature of Japanese poetic discoursenamely, that poems are so often occasional. In other words, Japanese poems were often written in specific situationssocial, political, and historical situations, in the broad sensethat need to be described for them to be understood in their own milieu.

Throughout the book, I employ the technical vocabulary of Japanese poetic discourse to frame my comments. Thus readers not familiar with the subject will encounter new technical terms such as kakekotoba (pivot word) and honkadori (allusive variation), the meanings of which should become clear through usage. (For those who want more detail, I have included appendixes.) Beyond that, however, I have not been bashful about using other terms that are of broader scope, such as metaphor, symbol, and prosody. While reducing Japanese poems to some Platonic notion of poetry writ large would be a mistake, not showing ways in which Japanese poetry is similar to poetry in other cultures would be equally foolish.

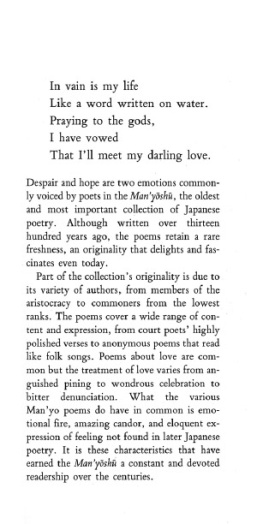

GENRES

Terminologies always do some harm to what they are meant to represent, and this is particularly true in the study of Japanese poetry. Throughout history, for instance, Japanese poets, critics, and scholars have often used the generic terms waka and uta almost interchangeably in reference to Japanese poetry in a general sense, while confusingly using those same terms to refer specifically to the highly canonical 5-7-5-7-7 genre that remained central to poetic discourse from the 700s to the 1800s. For the sake of clarity, in this book I use uta in reference to the general category of Japanese poetry and waka in the narrower sense of thirty-one-syllable poema defensible choice, I believe, however much it rankles the medievalist in me personally. The first six of my chapters are in that sense devoted to what might be termed subgenres within uta as an overarching but untidy discourse, in the rough chronological order in which they emerge in history: kodai kay (ancient song), ch ka (long poem), waka (short poem), kay (popular song), renga (linked verse), haikai (unorthodox poems), ky ka (comic waka ), and senry (comic haikai ). I have also included a chapter on Chinese poems by Japanese poets ( kanshi ; also karauta , in contrast to yamatouta ), a genre that was intertwined with Japanese-language poems throughout its long history. If this conception seems confusing I can only say that it is no more so than the reality I am trying to represent.