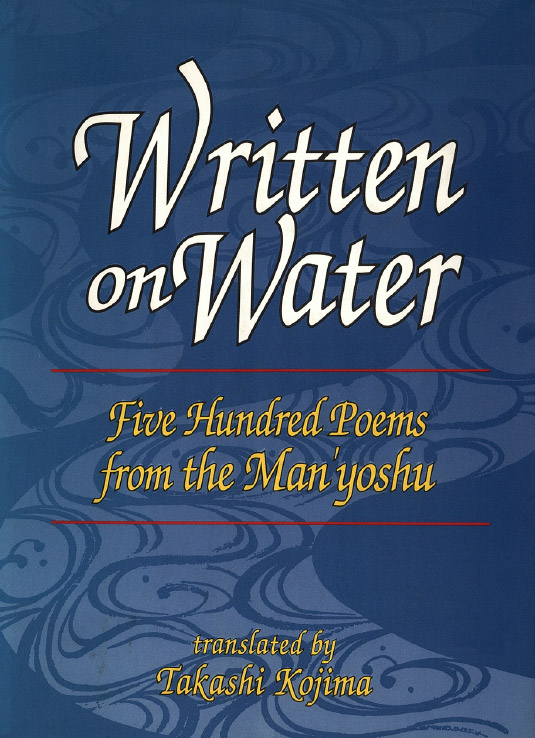

CHARLES E. TUTTLE COMPANY

Rutland, Vermont & Tokyo, Japan

Published by the Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc.

Osaki Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 141-0032.

LCC Card No. 95-60248

Acknowledgments

The Man'ysh , which consists of twenty volumes, was compiled during the course of 130 years, and its poetry is not systematically arranged or classified. In order to help the reader understand the Man'ysh and appreciate its lyricism and literary merits, I have selected five hundred poems from the total of 4, 516 and have divided them into three categories: poetry of known authorship, anonymous poetry, and poetry of envoys and frontier guards.

Without the kind help of many native English speakers, it would have been impossible to complete this work. Any mistakes are solely my responsibility.

Thanks are especially due to Mr. Jimmy Snyder, Dr. Piero Policicchio, and Mr. Lindsay O'Neil, who kindly read the greater part of my manuscript and gave me valuable suggestions.

My gratitude also goes to Mr. James Gardener, Mr. David Spiro, Mr. Gordon Barclay, Mr. William James, Mr. Grant Jennings, Mr. Todd Thacker, and Mr. John Patton.

Sincere thanks are also due to Mr. Yasui Nagafuji, professor of ancient Japanese literature at Meiji University; Mr. Tatsuyuki Got, music critic and former professor of musical theory at Kinj Music Academy, and his daughter, Ms. Takashima, an expert in traditional Japanese music; Mr. Michitaka Takeuchi, professor of Japanese music at K'unitachi Academy of Music; Mr. Takashi Imai, archaeologist; and Mrs. Takashi Imai, scholar of ancient Japanese literature. I also wish to thank Mr. Donald Iwamura, my son-in-law, and his son, Mr. Ken Iwamura; and Mrs. Lindsay Gene O'Neil, my granddaughter.

I wish to dedicate this book to Mr. and Mrs. Umenosuke Bessho, who kindly enabled me to go to college, and last but not least to my late dear wife, Yuki Kojima, who enabled me to devote myself to the accomplishment of this work.

A Note on the Translation

There is a school of thought that claims poetry cannot be translated. There is no way, states this argument, that the meaning, subtlety, depth, beauty, spirit, and essence of the original language can be transmuted into another language. The only possibility with poetry translation is approximation and compromise, and the result is little more than a wan shadow of the original.

Should the result emulate the formal conventions of the original language or should it take on the formal conventions of the new language? In other words, should a Japanese poem in translation try to approximate the sense and feeling of the original language or should it be translated into an English poem? To what degree should the translation hold its own as poetry, or should a rendering of meaning be the main aim?

With something as fluid and alive as language, and with poetry in particular, there is no simple right answer to such questions. Somehow an ideal mode or method of translation must be chosen, but anything attempted can only be partial. Even with poetry as close to contemporary English as that of, say, Rainer Maria Rilke, the translation problems are hardly small, but with a genre of poetry that follows linguistic conventions totally different from any Indo-European language, and one generated in the ancient past by a society that eludes comprehension by the West even today, the problems of translation take on entirely new nuances of the word "difficult."

Impossible? Probably. But even so, should any attempt to translate such poetry be avoided? That would mean that anyone who does not read Japanese and who is not conversant with eighth-century Japanese aristocratic society would be denied any indication of what the poetry of that period is about. Particularly, if the poetry in question is considered among mankind's great artistic legacies, should there not be some means of conveying, however partial and incomplete, an idea of what the original says?

Assuming that the answer is yes, assuming that the intrinsic worth of the Man'ysh makes its translation into English and any other European language an important contribution, how should the translation be done?

Should a scholar, who is not a poet and, with rare exceptions, does not possess the poet's gift of language, attempt to translate poetry of any kind (in the process adding to mankind s burden of footnotes)? Should a language specialista translatorwho is not a scholar attempt such translation?

How knotty the translation of this material is was made clear when a check of other English Man'ysh translations revealed that other translators' interpretations often were totally different from Mr. Kojima's and from each other's, some poems even being given opposite meanings. This should not be surprising, perhaps, because, as one commentator has pointed out, by the late Heian period, the language in which the Man'ysh was written had already become partially incomprehensible, and the following 800 years or so have complicated the task of interpreting the original poetry.

Without pretension and without scholar's pomp and posing, Mr. Kojima selected 500 poems out of the total of about 4, 500 and has given us a charming book. The translator of this little volume undertook a task rather like skiing down Mt. Blancthere are more reasons for not doing it than for doing it. Ignoring all the obstacles and the arguments for not attempting to translate the poetry of a society that might as well be Martian, he jumped into the task with verve and caring and a lifetime's experience as a translator of Japanese into English. This editor never met the translator, for Mr. Kojima passed away some years before this publication project was initiated. As a result, queries and problems could not be discussed, but had to be handled as English-language problems, and the few translation queries that occurred were given to another linguist to solve. Much gratitude goes to Ruth McCreery for her patient and supportive help on many levels.

Introduction

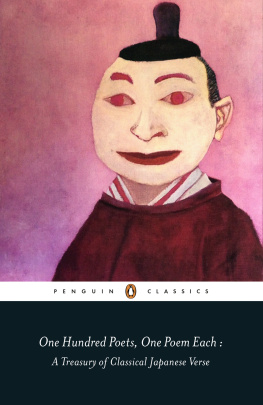

The Man'ysh is the oldest and yet the freshest and most important collection of Japanese poetry. It surpasses all later poetry collections and, in the quality of pure lyricism, it ranks among the masterpieces of world literature. It comprises, in twenty volumes, 4, 516 poems, most of which were composed over a period of 139 years, ending in the middle of the eighth centurya period that some consider to be the golden age of Japanese poetry.

The Man'ysh is a unique anthology, whose poets are people from all walks of life, ranging from members of the imperial family to the humblest level of society. The poems cover a wide range of expression and content, from court poets' highly polished expressions of delicate emotions and subtle sentiments, to anonymous poems that read like folk songs. These poems are a natural outpouring of genuine love and intense emotion and often directly reflect life experiences. Poems of later ages, though elegant and beautifully composed, often read like the product of imagined or fanciful experiences. Thus, one may well say that Man'y poetry is both ancient and yet among the freshest poetry of any time.