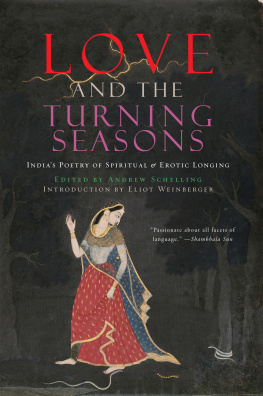

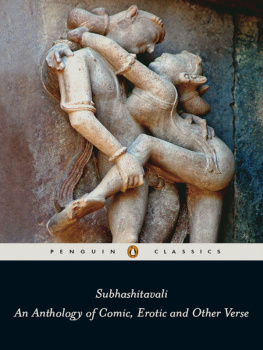

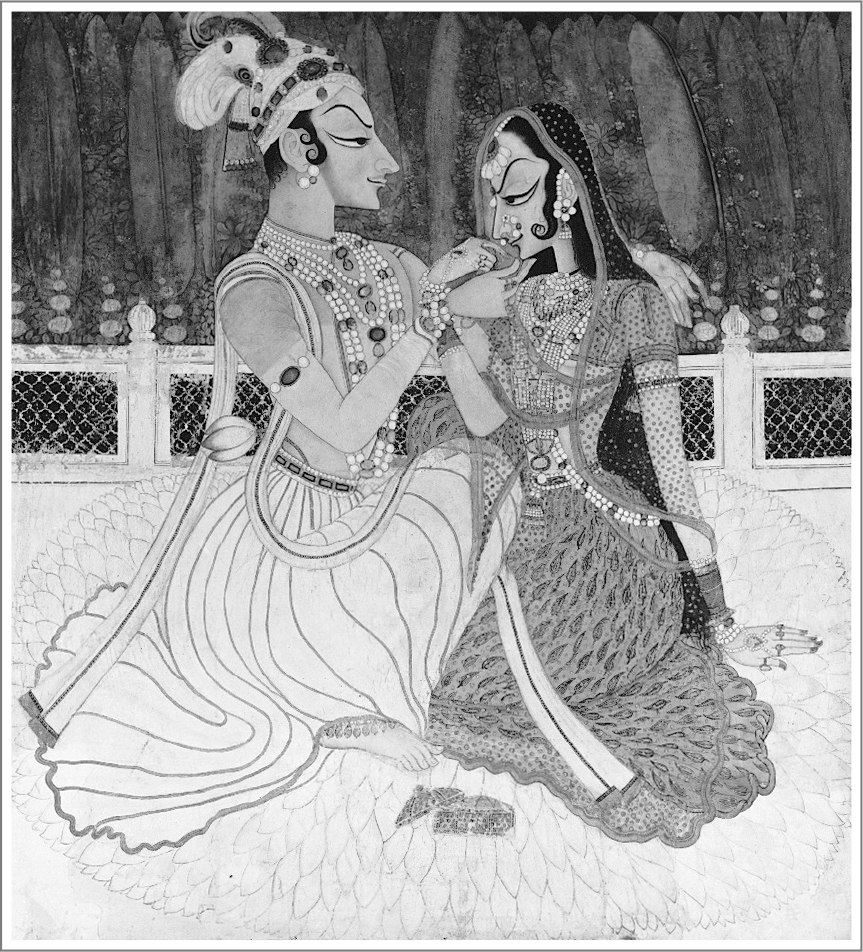

, ca. 17351757, used by permission of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Shambhala Publications, Inc. 4720 Walnut Street Boulder, Colorado 80301 www.shambhala.com 2004 by Andrew Schelling Poems originally appeared in

, 1998 by Andrew Schelling. Reprinted by permission of City Lights Books. All rights reserved.

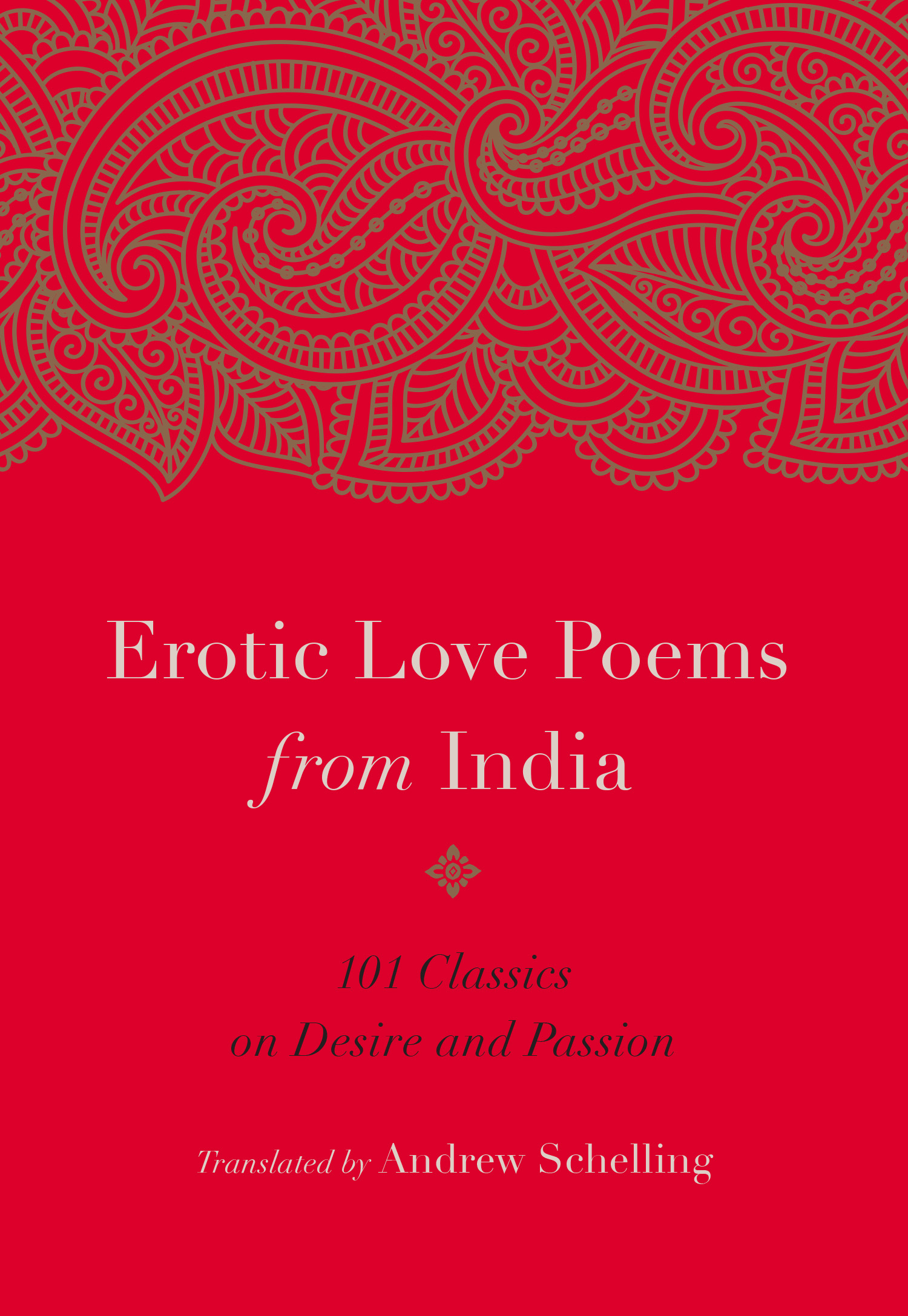

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover art by Bariskina/Shutterstock ISBN : 9781611807110 eISBN 9780834826151 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Control Number: 2018041921 v5.4 a For Dale Pendell (19472018) ethnobotanist, poet, philosopher nstyacaura kavijana There is no poet who is not a thief. Rajashekhara

INTRODUCTION

Love and the Turning Seasons It is well known, writes Anandavardhana, the ninth-century Kashmiri yogin and literary critic, that a single stanza of the poet Amarumay provide the taste of love equal to whats found in whole volumes. This statement, from his seminal work on Sanskrit poetics, the

Dhvanyaloka, is the first historic mention of the author to whom the verses in this volume are commonly attributed. The collection, known in Sanskrit as the

Amarushataka (One Hundred Poems of Amaru), was compiled in the eighth century and remains to this day one of the celebrated books of poetry in India. It is remarkable that nobody had translated the Amaru collection into American or English verse until 2004, when this book first came into print.

The popular account of the collections origin is so vivid, precise, and magical it could only have come from South Asia. Tradition says that the venerable Shankara (788820), Indias formidable master of Advaita Vedanta, or Nondual Philosophy, was locked in public debate with Mandanamishra, an advocate of a rival school of philosophy, the Mimamsa. Shankara was roundly defeating his opponent when Mandanamishras wife entered the fray. A sly and sportive lady, she posed a series of metaphysical questions to Shankara, couched in detailed metaphors of sexual love. Shankara, being celibate, was silenced. He requested an adjournment of the debate for a hundred days and nights to prepare a suitable response.

Leaving the stage and entrusting his body to his disciples, Shankara employed his yogic powers to enter the corpse of a just-deceased Kashmiri king named Amaru, already lying on an unlit funeral pyre. Amarus body quickenedthrilling the harem girls of Srinagar and Jammu, no doubtand Shankara in the borrowed form spent a hundred nights studying love at first hand, each with a different lady of Amarus court. He devoted his daytime hours to a careful examination of Vatsyayanas Kama Sutra and its commentaries. When his hundred nights had come to an end, Shankara added a few additional onesfor good luck, or simply to further his studies. Then he abandoned Amarus body to its fate and returned to his own. Taking the stage of debate, Shankara proved himself adept at the science that had formerly eluded him, and vanquished his opponent.

It is said that he composed a poem to memorialize the lesson of each of those nights, and all the manuscripts hold a few more or a few less than one hundred poems. Once he had gathered the poems into a volume, he signed the collection with Amarus namea touch of gratitude for the lessons received at Amarus court, through the kings own body. This story first appears in a fourteenth-century hagiography of Shankara, the Shankara-digvijaya by Madhava (also known as Vidyaranya). A later commentator on the Amarushataka, Ravichandra, provides a somewhat different account. In his version Shankara pays a visit to the court of the Kashmiri king. Amaru, a great sensualist as well as a warlord, was known to devote his waking hours to his carefully selected court ladies.

Hoping to improve his epicurean hosts karma, Shankara devises a hundred spiritually instructive poems in which he couches metaphysical teachings in the Sanskrit conventions of lovea lesson delivered in terms Amaru might understand. After Shankara recites the verses, the kings advisers and courtiers, too dull to catch the subtle intent, mock Shankara for composing a cycle of love poetry. If the renowned celibate has held to his vows, how could he detail such intimacies? Shankara fills with rage at their small-mindedness. Through his yogic powers he seizes Amarus body and delivers a spiritual exegesis of his poems through the kings mouth. And Amaru, hearing his own throat give angry vent to such teachings, is transformed on the spot. The best research by contemporary scholarship dates the Amarushataka to about the year 750 CE .

Indian scholars since Anandavardhanas time have attributed the work to a single poet, his name given as Amaru, Amaruka, or Amaraka. For over a thousand years India has read it as a single poem, or more properly, a cycle of interlocked stanzas that lead the reader along a carefully charted course. All the flavors or nuances of love are said to lie within the book, though youll notice that the emphasis falls more on the bitter taste of separation, jealousy, or betrayal than on the sweets of enjoyment. A survey of Amaru scholarship shows that the provenance of South Asian manuscripts is a complicated affair. Scholars remain divided on the most elemental details: when the Amaru collection was put together, by whom, and where. Most Western scholars regard it as an anthology, considering Amaru a compiler who may have included some of his own poems.

Indian scholars continue to credit a single author and to read it as a unified cycle. Whatever its origins, for thirteen hundred years this work has retained its reputation in India as one of the foundational collections of poetry. It is indispensable for any literate person with a classical education. Poets and critics still use its verses as a template against which to consider other poems. For our own era, it shows that long ago India developed a love poetry as original and vivid as that produced anywhere on the planet.

Only partly evident upon a first reading of the

Amarushataka is a hint of what holds together not only these verses of love and longing, but all of Indias old poetry: the presence of the revolving year.

Love and the turning seasons. This theme might serve, in more ways than one, as a gateway through which to approach the Amarushataka. Its poems do indeed portray the revolution of a calendar cycle, as do many Asian anthologies. Yet it is the cyclic migrations of the human heart that receive the most considered treatment. Monsoon rainstorms and the winds that announce them, the aromatic unfolding of jasmine creepers or a dozen species of water lotus, the mating songs of peacock and kingfisherthese rise and subside around the poems of old India like the chant of an archaic chorus. The central drama remains human. In India the love god is named Kama, Desire.

He has many epithets, one of them Ananga, Bodiless, because he slips unseen through the world with the hunters bow and arrows. His consort is Rati, Sexual Pleasure. At Kamas appearance, growling, tenebrous storm clouds mount the horizon, signaling the onset of monsoon season. The heat-withered vegetation rewakens, aromatic flowers unfurl their petals, wild animals venture into the open, and lightning creases the boiling dark sky. Driven by cool winds, intoxicating fragrances plunge down from forested mountain ranges, and pollinating insects thread the meadows and riparian groves. And humans? Humans in our sexual raptureeven our anguishrecuperate the oldest and most durable of traditions.