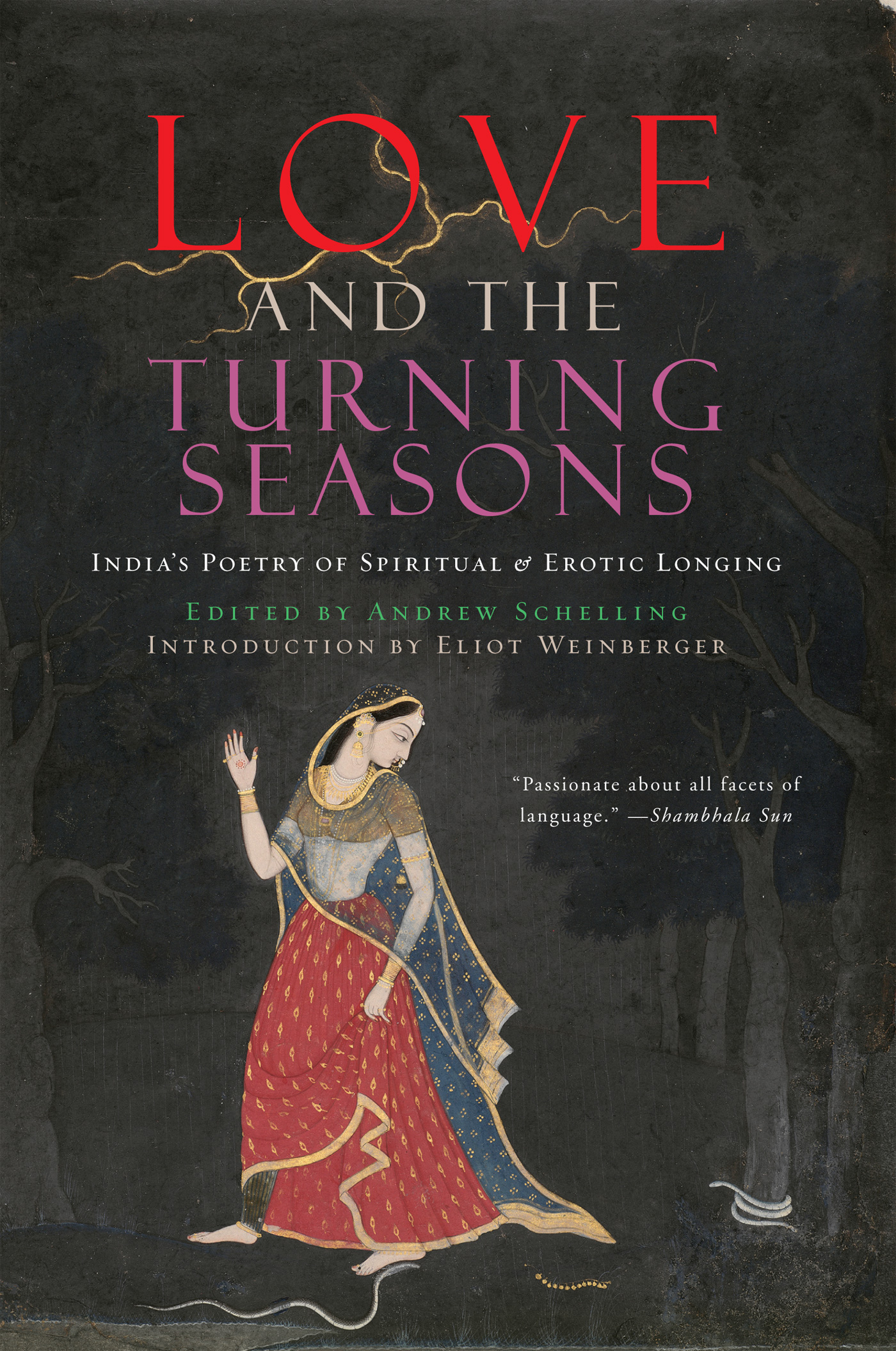

LOVE AND THE TURNING SEASONS

Translators

DEBEN BHATTACHARYA, ROBERT BLY, DILIP CHITRE, ANANDA COOMARASWAMY, VIDYA DEHEJIA, HANK HEIFETZ AND V. NARAYANA RAO, LINDA HESS AND SHUKDEO SINGH, JANE HIRSHFIELD, ARUN KOLATKAR, DENISE LEVERTOV AND EDWARD C. DIMOCK JR., ARVIND KRISHNA MEHROTRA, W.S. MERWIN AND J. MOUSSAIEFF MASSON, LEONARD NATHAN AND CLINTON SEELY, GIEVE PATEL, EZRA POUND, A.K. RAMANUJAN, ANDREW SCHELLING, GARY SNYDER, CHASE TWICHELL AND TONY K.

STEWART Copyright 2014 by Andrew Schelling All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover as follows: Love and the turning seasons : Indias poetry of spiritual & erotic longing / edited by Andrew Schelling. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-61902-241-6 1. Love poetry, IndicTranslations into English.

2.

Erotic poetry, IndicTranslations into English.

3. Indic poetryTranslations into English. 4. Indic poetry (English) I. Schelling, Andrew. II.

Title: Indias poetry of

spiritual & erotic longing. III. Title: Indias poetry

of spiritual and erotic longing. PK2978.E5L68 201 891.4dc23 2013028206 eISBN 978-1-61902-352-9

PB ISBN 978-1-61902-471-7 Cover design by David Bullen

Book Design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc Counterpoint Press 2560 Ninth Street Berkeley, CA 94710 www.counterpointpress.com Printed in the United States of America Distributed by Publishers Group West 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

: C ONTENTS

Afterword:

On Reading Indias Devotional Poetry

: I NTRODUCTION

Thou hast there in thy wrist a Sanskrit charge To conjugate infinitys dim marge Anew... ! H ART C RANE , T HE B RIDGE W E IN THE US inhabit a misplaced India, the land that Columbus thought he had found. Half a millennium later, the descendants of the original occupants are still bizarrely called Indians, no doubt because it has proven useful for the immigrants to treat the locals as foreigners.

But if the story of Indian America is a huge and largely tragic epic, alongside it is a little anthology of lyrics, idiosyncratic moments: the invention of American Indias. The mega-bestseller in the colonies, first published in 1751 and reprinted 54 times, was The Economy of Human Life: Translated from an Indian Manuscript Written by an Ancient Brahmin . This ancient book had been given by a lama in the Potala in Lhasa to a Chinese official named Caotsou, a man of grave and noble aspect, of great eloquence, who translated it from the Sanskrit (though, as he himself confesses, with an utter incapacity for reaching, in the Chinese language, the strength and sublimity of the original). Translated from Chinese into English by an unknown hand, the book presented the Oriental System of Morality in a series of maxims on modesty, prudence, piety, and temperance, that seemed to emanate more from a Calvinist pulpit than the environs of an adorned lingam: The first step to being wise is to know that thou are ignorant; The terrors of death are no terrors to the good; Take unto thyself a wife and become a faithful member of society; Keep the desires of thy heart within the bounds of moderation; Receive not a favor from the hand of the proud. [The book, now believed to be the work of an English bibliophile named Robert Dodsley, had a curious afterlife. It was reprinted verbatim in 1925 by a group of California Rosicrucians as Unto Thee I Grant, the Secret Wisdom of Tibet, which had been transmitted to the Himalayas by the pharaoh Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten perennial occultist source of the worlds religions).

The text, in turn, became part of the ultra-secret Circle 7 Koran of the inner-city Moorish Science Temple, founded in Newark in 1913 by the prophet Noble Drew Ali (born Timothy Drew) and relocated to Chicago in the 1920s. Among the initiates of the Circle 7 Koran were Wallace Fard and Elijah Muhammad, who adapted the sacred knowledge to create the Nation of Islam. There is a line, then, however jagged, from pseudo-Hinduism to Malcolm X.] Actual artifacts from India began to arrive in New England with the opening of the India trade in 1784: muslins, Bengal ginghams and paisley shawls, monkeys and parrots, tamarind and ginger, knicknacks and small statues of the uncanny gods. The first real Indian a Tamil from Madras, with a soft countenance but well-proportioned body showed up in 1790; six years later, the first elephant, named Old Bet, was a sensation. The East Marine Society, made up of sailors who had been to Asia, had a spectacular annual parade in Salem, with a palanquin borne by Negroes dressed in the Indian manner. Intellectual Indophilia begins with both global trade and Sir William Jones discovery of the Indo-European roots of many languages, the realization that those strange others were somehow part of us.

Samuel Adams, in his retirement devouring books on the East, wrote to Jefferson that Indeed Newton himself, appears to have discovered nothing that was not known to the Ancient Indians. He has only furnished more ample demonstrations of the doctrines they taught. Post-Revolutionary Americas belief in (if not practice of) universal human rights was leading to a preoccupation with a universal human religion. One of the responses was Unitarianism, which found a bridge between the seemingly dissimilar Hinduism and Christianity in the figure of Rammohun Roy, who translated some of the Vedas and the Upanishads and founded the Brahmo Samaj, devoted to recuperating an imagined monotheistic ur-Hinduism, sweeping away the million gods. When Roy moved to London and converted to Christianity (or more exactly, the universal Hindu-Christianity) he became a Unitarian star. Roy was read by Emerson, who said that India makes Europe appear the land of trifles.

In the Vedas, the Bhagavad-Gita , and the Vishnu Purana , he found the highest expression of the conception of the fundamental Unity. His philosophical terms, the Over-Soul and the Higher Self, are plainly derived from the Hindu Brahman and atman; his versions of illusion and fate come from maya and karma . Curiously, though his beloved aunt sent him Sanskrit poems and he himself extensively adapted poems by Hafiz, Saadi, and other Persian and Arabic poets, Indian poetry didnt enter into his Indo-worldview and India only appears twice in his poetry: a lament for dead New England farmers, mysteriously titled Hamatreya, (a word otherwise unknown, though possibly derived from Maitreya, the future Buddha, which doesnt illuminate the poem) and the often-anthologized Brahma (If the red slayer think he slays, / Or if the slain think he is slain, / They know not well the subtle ways/ I keep, and pass, and turn again.), a poem that eerily seems indeed to come from the future: the voice of another Indophile, Yeats. Thoreau discovered India through Emerson, and surpassed him in unqualified enthusiasm: I cannot read a sentence in the book of the Hindoos [probably either the Laws of Manu or the Bhagavad-Gita ] without being elevated as upon the table-land of the Ghauts. It has such a rhythm as the winds of the desert, such a tide as the Ganges, and seems as superior to criticism as the Himmaleh Mounts. (Some have seen his retreat to the pond as an act of yogic austerity, though his sisters often brought him cookies.) He was given a large library of Indian books, for which, typically, he built a special bookcase out of driftwood, and translated from the French some Buddhist texts and a story from the Mahabharata . (Some have seen his retreat to the pond as an act of yogic austerity, though his sisters often brought him cookies.) He was given a large library of Indian books, for which, typically, he built a special bookcase out of driftwood, and translated from the French some Buddhist texts and a story from the Mahabharata .

Next page