PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd, 7th Floor, Infinity Tower C, DLF Cyber City, Gurgaon - 122 002, Haryana, India

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published by Penguin Books India 1996

www.penguinbooksindia.com

Copyright Penguin Books India 1996

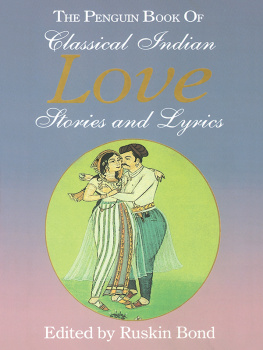

This is from Ruskin Bonds collection of old postcards.

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-0-140-25887-5

This digital edition published in 2014.

e-ISBN: 978-9-351-18814-8

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior written consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser and without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above-mentioned publisher of this book.

PENGUIN BOOKS

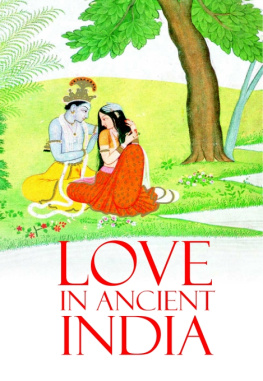

THE PENGUIN BOOK OF CLASSICAL INDIAN LOVE STORIES AND LYRICS

Ruskin Bond was born in Kasauli, Himachal Pradesh, in 1934, and grew up in Jamnagar (Gujarat), Dehradun and Shimla. In the course of a writing career spanning forty years, he has written over a hundred short stories, essays, novels and more than thirty books for children. Three collections of short stories, The Night Train at Deoli, Time Stops at Shamli and Our Trees Still Grow in Dehra have been published by Penguin India. He has also edited two anthologies, The Penguin Book of Indian Ghost Stories and The Penguin Book of Indian Railway Stories.

The Room on the Roof was his first novel, written when he was seventeen, and it received the John Llewellyn Rhys Memorial Prize in 1957. Vagrants in the Valley was also written in his teens and picks up from where The Room on the Roof leaves off. These two novellas were published in one volume by Penguin India in 1993 as was a much-acclaimed collection of his non-fiction writing, Rain in the Mountains. Delhi is not Far: The Best of Ruskin Bond was published by Penguin India the following year.

Ruskin Bond received the Sahitya Akademi Award for English writing in India for 1992, for Our Trees Still Grow in Dehra.

Kashmiri Song

Pale hands I loved beside the Shalimar,

Where are you now? Who lies beneath your spell?

Whom do you lead on Raptures roadway, far,

Before you agonize them in farewell?

Oh, pale dispensers of my Joys and Pains.

Holding the doors of Heaven and of Hell,

How the hot blood rushed wildly through the veins

Beneath your touch, until you waved farewell.

Pale hands, pink-tipped, like lotus buds that float

On these cool waters where we used to dwell,

I would rather have felt you round my throat

Crushing out life, than waving me farewell!

Lawrence Hope, Songs from the Garden of Kama

THE PENGUIN BOOK OF

CLASSICAL INDIAN LOVE STORIES AND LYRICS

Introduction

Kamadevas arrows of love were made of flowers. His divine commander was vasanta (spring), who brought the trees and flowers into blossom and softened all creation for the sweet, irresistible attack of the god of love.

This nature-god is most in tune with Indias Classical Age (roughly, the first thousand years ad), a time when the land was dominated by forests teeming with bird and animal life, and the human population was comparatively small and scattered. Countless kingdoms, large and small, made up the rich bejewelled pattern of India. Around the kings palace or fort grew small towns and bazaars and caravanserais for travellers, but just outside the city gates there was considerable verdure, with areas of cultivation fringing the great forests. This was a fit setting for the great legends and romances of gods and heroes and heroines. The Ramayana and the Mahabharata belonged to the earlier, Epic Age, but they provided stories that continued to be told and retold, culminating in Kalidasas great verse-drama, Shakuntala, written in the early years of the new millennium. The great achievement of Shakuntala is in part due to its creators love of nature. He is at his best in the lyrical passages describing the flora and fauna of the land. Shakuntala herself is half bird, her name being derived from the shakuntas or birds with which she held such easy converse.

Shakuntala is romantic and escapist, but this is not always the case with other writings of the period. The Classical Age saw the flourishing of the Sanskrit language, with an outpouring of poetry and drama. And Kamadeva was no chubby, infant Cupid. He was a mischievous, dexterous, youthful deity. His presence, visible or invisible, is felt in almost every story, love poem or prose work.

The literature of love and the literature of love-making are different. In the stories, poems and extracts presented here we find passion, desire, tenderness,jealousy, sensuality, even platonic love. But the art of love-making, described so inexhaustibly (exhaustingly?) in Vatsayanas Kamasutra (fourth century AD) does not really fall in the purview of this collection. It is not so much a story as a manual of sexual prowess. And it is easily available everywhere in many handsome editions.

In making this selection, I was looking for love literature that was not too well-known but which, nevertheless, was of high quality. Naturally I drew upon legend and folklore, of which there is a fair sampling; upon recent translations of classical Sanskrit, Tamil and Kannada literature; upon retellings from the epics; and upon some of the formative literature of the last century. Even then, I felt that something was missingsome tantalizing fragment, forgotten, neglected, unknown to me (and probably to the general reader) and which in some way sought to draw attention to itself.