Learned in sacred literature, a seasoned critic of dance, wily in the game of dice and a connoisseur of human beauty, this parrot called Vaishampayana is the most wonderful of all the wonderful things in the world.

Bana is among the three most important prose writers in classical Sanskrit, all of whom lived in the late sixth and early seventh centuries AD . It is clear, from his writings, that his mind was amazingly modern, humane and sensitive. Bana had a healthy irreverence towards many of the established orthodoxies of his time and his strength lies in his skill as a creator of characters vibrant with life and individuality.

Kadambari is a lyrical prose romance that narrates the love story of Kadambari, a Gandharva princess, and Chandrapida, a prince who is eventually revealed to be the moon god. Acclaimed as a great literary work, it is replete with eloquent descriptions of palaces, forests, mountains, gardens, sunrises and sunsets and love in separation and fulfilment. Featuring an intriguing parrot-narrator, the story progresses as a delightful romantic thriller, in which the earthly and the divine blend in idyllic splendour.

Translated with an introduction by PADMINI RAJAPPA

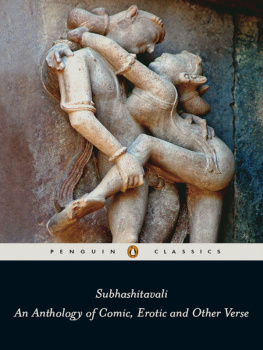

Cover: Parkiya-Nayika Sringara, Kangra, Pahari, circa AD 1800 courtesy National Museum.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to Vijaya Deshmukh for introducing me to the Sanskrit language. My special thanks are due to Yashodhara as well as Bhagyalatha Pataskar for having taken me through the intricacies of the grammar of Panini. I am grateful to Dr. Saroja Bhate for putting me in touch with Yashodhara and for having encouraged me in the study of the language.

It was Dr. Saroj Deshpande who introduced me to Bana and taught me how to unravel his tangled style. I express my sincere thanks to her.

My very special thanks are due to Lalitha Ganguly for those countless hours of study without which this translation would not have been possible; and to young Surabhi for having read the manuscript and pronounced it interesting.

I am deeply obliged to Satya Saran for reading the first few chapters and encouraging me to submit the manuscript to Penguin Books.

My grateful thanks to Paromita for getting the work into shape with careful editing. It has been a pleasure working with her.

Prologue

-1-

O nce upon a time there was a king named Shudraka who reigned over the whole earth. He was a great king, a second Indra. All the rulers of the world without exception bowed to his authority. He had subdued them all, by intimidation and by conciliation. He had thus become Lord Protector of Dame Earth. On him were seen all the marks of a great sovereign, a chakravarthi.

Like Lord Vishnu, Chakradhara, the wielder of the discus, Shudraka too carried the discus and the conchas signson the palms of his hands. Like Shiva he too had vanquished Manmathaby his surpassing beauty. Like Kamalayoni, the one born on the lotus and the rider of the rajahamsa, the stately swan, he too had quelled the pride of the rajahamsasthe powerful monarchs of the world.

Supreme in valour, Shudraka performed marvellous deeds, and great sacrifices. He was verily a mirror in whom all learning found its reflection. He was the source of all arts, the fount of all aesthetic sensibility and truly a storehouse of all virtues.

It may well be said that the god Dharma found his abode in Shudrakas dutiful mind, Yama in his righteous anger. Kubera resided in his kindness and Agni in his valour. The strength of his arms reflected the stability of the earth and the brilliance of his eyes was the splendour of Lakshmi. Saraswati lingered in his learned speech and Chandra shone from his lustrous face. In his might there was Vayu and in his incomparable intellect there was Brhaspati. In his beauty of form there was Manmatha and in his splendour Savitr. Exhibiting all these divine perfections Shudraka was indeed the very image of the Vishvarupa of Lord Narayana.

When Shudraka ruled there was peace on earth. The people led noble and happy lives. There was deviousness only in the twisting trellises of their windows, blemishes only on the sheaths of their swords, due to disuse; there was spying only in lovers quarrels, vacant houses only on ludo boards. The only tears shed were those caused by the smoking sacrificial fires; the only whipping known was the whipping of the horses and the only bow that twanged was the bow of Manmatha.

Shudrakas capital was at Vidisha, a city so vast that it could have been the womb that gave birth to all the three worlds. It was so righteous a city that one could well wonder if the noble Krita Yuga of yore, in fear of being assaulted by Kaliyuga from all sides, had compressed itself to the dimensions of this city and taken refuge in it.

Vidisha was skirted by the river Vetravati whose waves were continually shattered by the bouncing breasts of the beauties of Malwa frolicking in the water. The waters were often stained a twilight-red by the vermilion on the forehead of the battle-victorious elephants diving into them. Her banks resounded with the chattering of the excited swans.

Having subdued all the three worlds King Shudraka was free of all worries and bore the burden of ruling lightly, like the armlets on his arms. Besides, he had able ministers to assist him in the task. These ministers were men of the noblest lineages, wiser than Brhaspati himself. Their minds were clear as crystal due to their constant study of the sacred and secular texts. They were alert and selfless and affectionate. Is it any wonder then that the kings youthful days were spent in the pleasurable company of the vassal princes who had come from far and wide to pay him homageall comparable to him in age, learning, comportment and valour. They too had honed their intellects in the study and practice of the various arts; they too were experts in all forms of literary composition. Endowed with magnificent physiques with hard, well-developed muscles in their chest and arms they too had proved their valour by vanquishing repeatedly the enemy elephants and riding on them like lion cubs. Yet they were invariably modest and full of courtesy.

The kings time was spent mostly in the company of these princes in various pursuits. He would, of course, go hunting with them, seemingly intent on emptying the forest of animals, with the incessant discharge of his arrows. But he was interested in gentler pastimes as well. He was fond of making music; he would play on the mridangam, his armlets swinging and his earrings tinkling like bells; or he would strum the veena. Sometimes he would organize learned seminars at which he would try his hand at composition; or he would discuss points in philosophy. Sometimes he would listen to the reading of literary works of various types as well as the itihasas and the puranas. Or he and his friends would devise various literary and language games to divert their minds. They also spent some of the time in ministering to the comforts of the visiting ascetics.

Whether it was a result of his excessive preoccupation with acts of valour, or whether it was a natural feature of his innately lofty mind, whatever it was due to, Shudrakas indifference to women was most bewildering. The king was in his prime and was exceedingly handsome. His antapura was full of women of noble descent whose beauty and charm could have put Rati in the shade. They were modest and appealing as well. The ministers, for their part, were importuning the king on the necessity of producing heirs to the throne. But all this had no effect on him. If anything the king appeared at times to exhibit a positive hatred towards all pleasures of the flesh.