Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

This digital edition published in 2016.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

W.J. Wilkins

Hindu Mythology, Vedic and Puranic

Introduction

Humans are governed by powerful sentiments such as heroism, envy and covetousness, love and sexual desireperhaps the most primal emotion. Why are we so obsessed with sex? What is it that makes us behave the way we do when in love? These questions have been the subject of much debate and analyses, but of one thing we can be certain: sexual desire remains one of mankinds least understood urges.

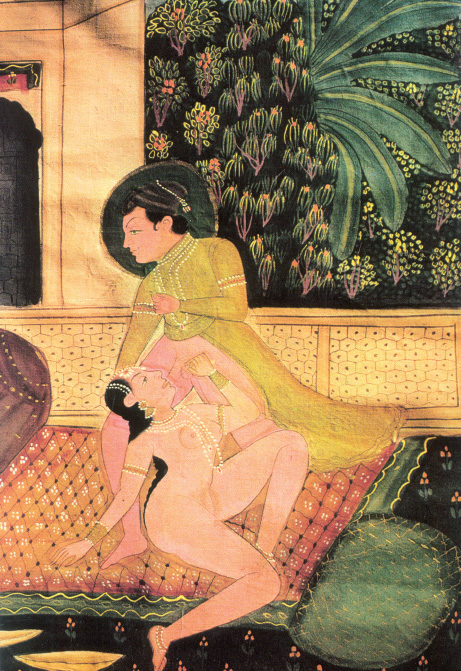

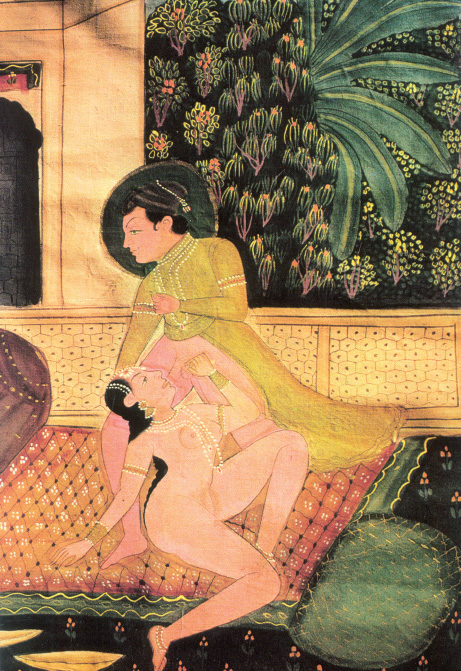

According to Hindu cosmology, desire, personified as Kama, is an essential aspect of the cosmic being and the cause behind every longing. Sexuality and spirituality were not separate realms, and ancient Hindus celebrated life and love as a continuous utsav or carnival. Treated as both art and science, sexuality has been researched, discussed and analyzed for well over three thousand years on the Indian subcontinent. From the Rg Veda to the Kamasutra, the sexual urge has been exploredwithout guilt, hypocrisy or duplicity.

But ancient Indians believed this pleasure had to be tempered with knowledge of dharma. Eroticism was considered valuable only if it did not infringe on the rights and sentiments of others: the pursuit of pleasure needed to be carried out with sensitivity, reverence for life and most importantly, self control. It comes as no surprise then that chastity belts are unheard of in India. In fact, the penalty for adultery in ancient India was never more rigorous than a ritual bath or a donation. Says the sage Vatsyayana, author of the Kamasutra, Reasonable people aware of the importance of virtue, money and pleasure, as well as social convention, will never let themselves be led astray by passion.

By the medieval period, however, the liberal beliefs of the ancients had undergone a marked change. Monogamy became the norm and the other woman, who occupies pride of place in the Kamasutra, disappeared. For all its emphasis on marital fidelity, this era witnessed the emergence of the religious-erotic cult of Radha and Krishna. Tantra philosophy, which believed in the compatibility of human sexuality and spirituality, emerged in the early medieval period. Sexuality was liberally expressed in temple art and architecture. In contrast to medieval synagogues, churches and mosques, all forms of sexual expressionhetero- and homosexual, auto-eroticism, even group sex and bestialitywere displayed almost defiantly on the walls of temples in Khajuraho, Konark and Palampet, among others. Eroticism also found its way into the literature of the time. Sample these lines from the Rtusamhara by the great Sanskrit playwright Kalidasa:

Enjoyed long through the cold night in love-play

Unceasing by their lusty young husbands

in an excess of passion, driving, unrelenting, women just stepped into youth move at the close of night slowly

reeling, wrung-out with aching thighs.

(Kalidasa, The Loom of Time,

translated by Chandra Rajan)

Several erotic texts were written between the tenth and eighteenth centuries in keeping with the tradition of the Kamasutra.

The earliest of these texts is, surprisingly, a Buddhist one called Nagarasarvasvam (A Guide for a Townsman), written by a monk Bhikshu Padmasri in the tenth century. Two of the most famous medieval erotic texts are Rati Rahasyam (The Secrets of Love), written by the poet Kukkola in the twelfth century, and Ananga Ranga, written by Kalyanamalla in the fifteenth century. The Ratishastra, which discusses procreation and ideal behaviour expected of married couples in Hindu homes, also reflects the values and norms of medieval Indian society. Many other texts such as Janavashya, Ratiratnapradipika, Panchasayaka and Manmathasutra followed well into the eighteenth century.

Attitudes towards sexuality in contemporary Indian society are vastly different from those of the past. Insecurities abound as old values crumble and get replaced by new, uninformed notions and a prurient popular culture. As traditional norms are challenged in a rapidly changing India, sexual repression and violence have become the norm.

Delving into some of our erotic texts could help put into perspective some of the problems we face today. These texts are not meant to be titillating reading on the sexual proclivities of Indias past. Rather, by highlighting love and respect, they emphasize the right of every man and woman to seek sexual pleasure. They stress, with wit and humour, that sex, like everything else in life, requires energy and attentiveness, and when learnt and practised, can be developed into a fine art.

Five medieval texts that have survived the ravages of time are included in this bookPururavasa Manasijasutram, Narmakelikutuhala Samvadam, Smarapradipika, Manmatha Samhita and Kadambari Swikaranakarika.

These, along with other medieval erotic texts, have often been dismissed by modern scholars as mere imitations of the Kamasutra with little literary value and almost no new data. Many other texts have been lost and several others languish as manuscripts or mouldy Sanskrit texts in the dusty backrooms of long forgotten libraries. A closer examination, however, shows that these texts are quite different from the Kamasutra: overt displays of affection are discouraged, foreplay and oral sex assume more importance, and much more is known about impotency, premature ejaculation, menstruation, orgasms and the G-spot. In addition, these texts discuss monogamy, polygamy, prostitution, infidelity, etc.issues that do not feature in the Kamasutra.

Frank and forthright, these texts make no concession or apology for their explicitness, and do not attempt to couch facts in symbolism and metaphor. Nor are they jaded treatises on sexual positions. The Kadambari Swikaranakarika ventures into areas the Kamasutra does not even mentionit recognizes the fact that women need more time to get aroused and recommends the use of alcohol to intensify arousal. The