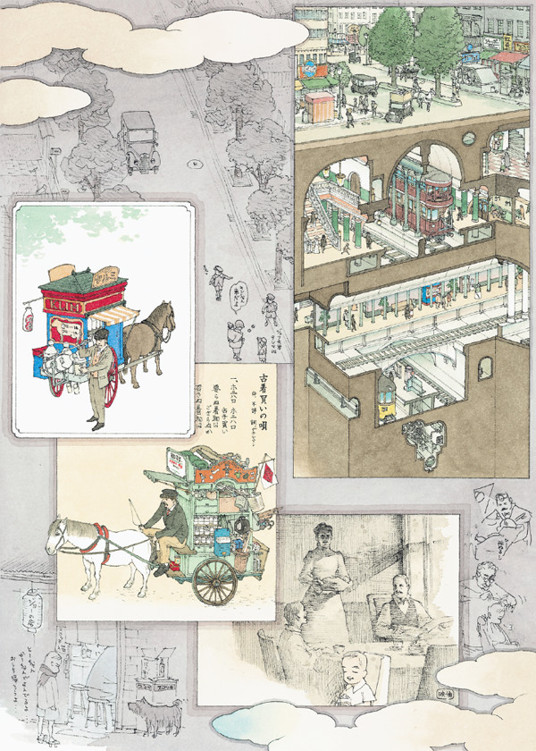

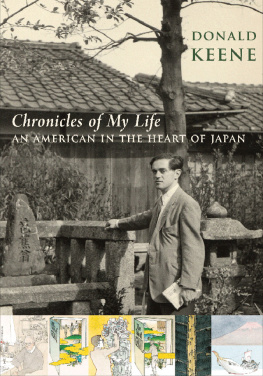

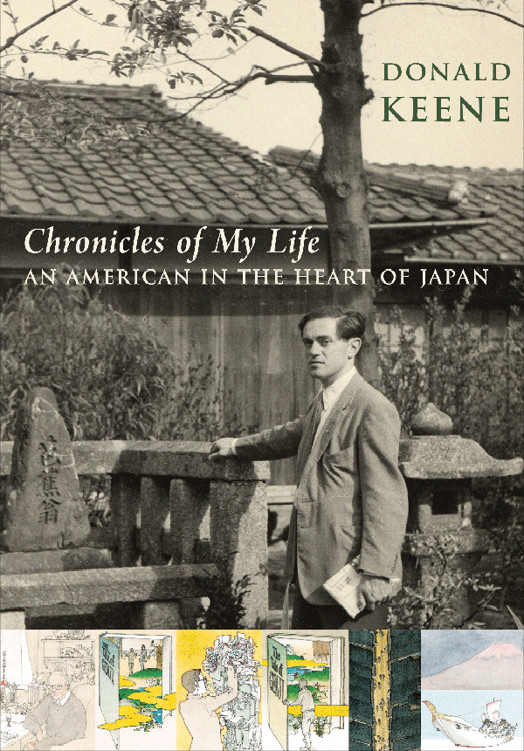

Chronicles of My Life

DONALD

KEENE

Chronicles of My Life

AN AMERICAN IN THE HEART OF JAPAN

ILLUSTRATIONS BY AKIRA YAMAGUCHI

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS  NEW YORK

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2008 Donald Keene

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-51348-7

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Keene, Donald.

Chronicles of my life : an American in the heart of Japan/Donald Keene ; illustrations by Akira Yamaguchi.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-231-14440-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-14441-4 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-51348-7 (electronic)

1. Keene, Donald. 2. CriticsUnited States Biography. 3. JapanologistsUnited States Biography. I. Yamaguchi, Akira. II. Title.

PL713.K43A3 2008

895.609dc22 2007038841

[B]

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

When I was a child (and even much later), there was almost nothing to make me think of Japan. The word kimono (however I pronounced it) was probably the only word of Japanese I knew, but thanks to my collection of postage stamps, I was aware that Japanese and Chinese writing was similar or perhaps the same. That was the extent of my familiarity with the Japanese language and Japanese culture. I never saw a Japanese film, never listened to a Japanese piece of music, never heard a word of Japanese spoken. It was not until I was in junior high school that I even saw a Japanese, a girl in my class. I knew infinitely less about Japan than the average Japanese boy knows about America.

A Japanese boy is almost certainly familiar with at least the English words relating to baseball. He will have noticed the names of the players written in roman letters on the back of their uniforms and the name of their team embroidered in English on their chests. He will have seen American films, sung or played American tunes, learned the names of a few American presidents and rock musicians. He will know many English words even without realizing that they are foreign.

Although I attended a high school that has produced a surprisingly large number of Nobel Prize winners, our education was more or less restricted to the history, literature, and science of the West. I dont recall a single thing I was taught about Japan in my history classes, though probably Commodore Matthew Perrys great achievement in opening Japan was mentioned at some point. When I was about ten, I received at Christmas an encyclopedia for children that had three supplementary volumes, one each devoted to Japan, France, and Holland. I dont know why these countries had been selected. Perhaps it was because they lent themselves to attractive illustrations: humpbacked bridges for Japan, lords and ladies dancing on the bridge at Avignon for France, and wooden shoes for Holland. I also learned from the Japan volume that the Japanese wrote very short poems called haiku . That was my introduction to Japanese literature.

Ignorance of Japan was not unusual for a boy growing up seventy years ago in America, but growing up in New York set me apart from other American boys in many other ways as well. For example, Japanese friends, who assume that every American learns as a child how to drive a car, are surprised when they discover that I am unable to drive. Boys who grow up elsewhere in America need to know how to drive, but New Yorkers find travel by subway or bus the normal way of getting around, and relatively few own a car.

I grew up in a middle-class suburb where some people did have cars. My father in fact owned cars of various kinds, the size and condition depending on his financial situation, but they held no allure for me. I preferred the subway and was proud (at the age of nine) to be allowed to travel alone. Cars were not an important part of my life. There were never many vehicles on the street where I lived, and children played in the middle of the street, resenting every car that intruded.

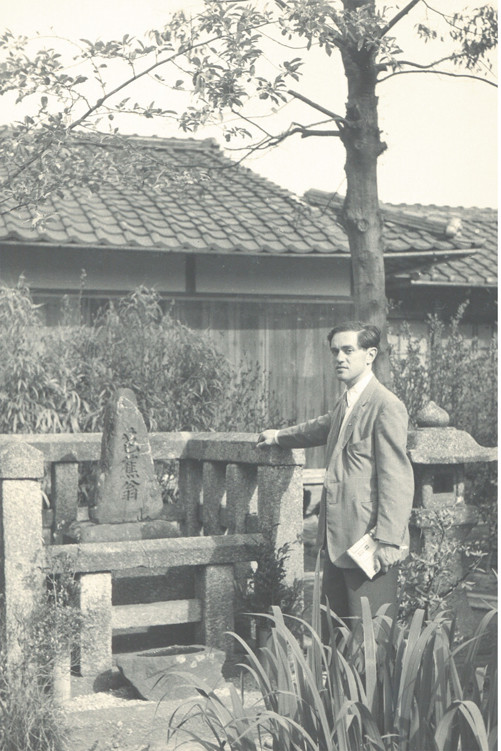

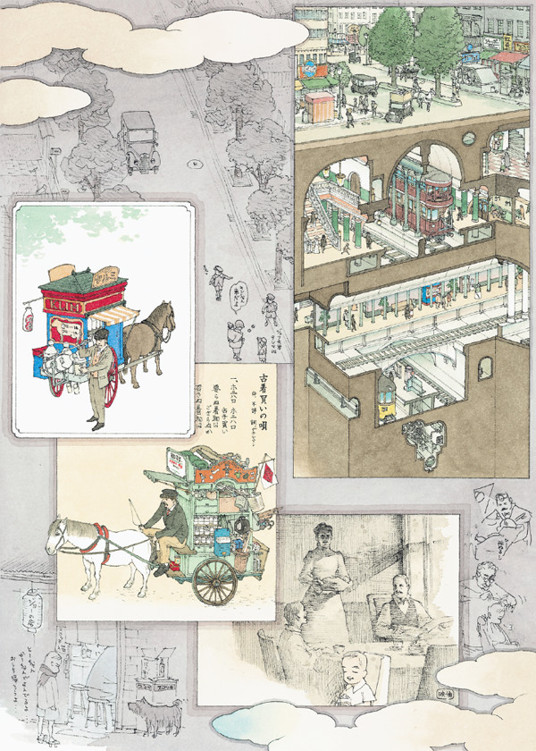

Cars were not the only vehicles. Every morning the milk was delivered from a cart pulled by a horse. The horse knew exactly at which houses to stop and gave the milkman just the proper amount of time to place the milk bottles by each kitchen door. Junkmen sometimes passed along the street in horse carts singing a ditty urging people to sell their used clothes.

Not long ago, for the first time in more than sixty years, I visited the street where I grew up. I thought then how lucky I was to have lived in a house on a street with trees on both sides, but as a boy I did not realize my luck and wished that I lived somewhere else, anywhere else.

My greatest pleasure was going to the movies. I went cheerfully to the dentist and even to the barbershop (which I hated even more than the dentist) if, as a reward, my mother promised to take me to a movie afterward. I liked every film, indiscriminately, but I was attracted especially to those that showed typical American families living in small towns. The father in the film was always kindly, with gray hair and moustache, and the mother was constantly baking pies. The problems of the boys in the filmswhether or not they would be chosen for the baseball team or whether their date would show up on Saturday nightwere not problems that bothered me. I envied them because their lives seemed so much more cheerful than mine.

The Great Depression began when I was seven. From then on, conversation at the dinner table often was related to my fathers financial problems, a subject never discussed by people in the films. Not much that happened at the time arouses nostalgia. In 1934 my sister died, leaving me an only child. From that time on, the relations between my parents deteriorated in a way that even I could sense. One day my father stormed out of the house, saying he would not return. My mother asked me to beg him to come back. My father asked, Did your mother tell you to do this? I said no, and he yielded, but the nightly disputes grew ever more audible. One night I overheard my father say that the only reason why he had continued to live with my mother was that he had loved my sister, but now that she was dead this reason no longer existed. Perhaps he did not really mean these words. They may have been spoken in a flash of anger, but I never forgot them. The final separation of my parents and the move of my mother and myself from our house to a dreary apartment occurred when I was fifteen.

An even more painful factor in my unhappiness was caused by my being clumsy in sports. Unlike the boys in the films, sports gave me no pleasure. I halfheartedly attempted to join other boys playing baseball, but once they discovered how badly I batted and ran, they did not want me on their team. My mother sometimes bribed the boys to include me in their games, but this never lasted for long.

I resigned myself to being a failure. My hope was that when I became an adult (I imagined this would be when I was eighteen), nobody would expect me to throw or hit a ball. Other boys who were poor at sports overcame their inferiority by sheer determination, but I never really tried, sure that nothing would ever improve my ability.

Next page

NEW YORK

NEW YORK