THE HEART OF HAIKU

BY JANE HIRSHFIELD

(HAIKU TRANSLATIONS BY JANE HIRSHFIELD AND MARIKO ARATANI

In this mortal frame of mine, which is made of a hundred bones and nine orifices, there is something, and this something is called a wind-swept spirit, for lack of a better name, for it is much like a thin drapery that is torn and swept away at the slightest stir of the wind. This something in me took to writing poetry years ago, merely to amuse itself at first, but finally making it its lifelong business. It must be admitted, however, that there were times when it sank into such dejection that it was almost ready to drop its pursuit, or again times when it was so puffed up with pride that it exulted in vain victories over others. Indeed, ever since it began to write poetry, it has never found peace with itself, always wavering between doubts of one kind and another. At one time it wanted to gain security by entering the service of a court, and at another it wished to measure the depth of its ignorance by trying to be a scholar, but it was prevented from either because of its unquenchable love of poetry. The fact is, it knows no other art than the art of writing poetry, and therefore, it hangs on to it more or less blindly.

Matsuo Bash, Journal of a Travel-Worn Satchel

(tr. Nobuyuki Yuasa)

Matsuo Bash wrote these sentences in 1687. He was forty-three. By then, his restless wind-swept spirit had substantially remade the shape of Japanese literature, by taking a verse form of almost unfathomable brevity and transforming it into a near-weightless, durable instrument for exploring a single moments precise perception and resinous depths.

A few of the most well known glimpses:

old pond:

frog leaps in

the sound of water

furuike ya kawazu tobikomu mizu no oto

silence:

the cicadas cry

soaks into stone

shizukasaya iwa ni shimiiru semi no koe

spring leaving

birds cry,

fishes eyes fill with tears

yukuharu ya tori naki uo no me wa namida

horsefly

among the blossoms

dont eat it, friend sparrow

hanani asobu abu na kurai so tomosuzume

in the fishmarket

even the gums of the salted sea-bream

look cold

shiodai no haguki mo samushi uo no tana

summer grasses:

whats left

of warriors dreams

natsugusa ya tsuwa mono domo ga yume no ato

In his poems and in his teaching of other poets, Bash set forth a simple, deeply useful reminder: that if you see for yourself, hear for yourself, and enter deeply enough this seeing and hearing, all things will speak with and through you. To learn about the pine tree, he told his students, go to the pine tree; to learn from the bamboo, study bamboo. He found in every life and object an equal potential for insight and expansion. A good subject for haiku, he suggested, is a crow picking mud-snails from between a rice paddys plants. Seen truly, he taught, there is nothing that does not become a flower, a moon. But unless things are seen with fresh eyes, he added, nothings worth writing down.

A wanderer all his life both in body and spirit, Bash concerned himself less with destination than with the quality of the travellers attention. A poem, he said, only exists while its on the writing desk; by the time its ink has dried, it should be recognized as just a scrap of paper. In poetry as in life, he saw each moment as gate-latch. Permeability mattered more in this process than product or will: If we were to gain mastery over things, we would find their lives would vanish under us without a trace.

*

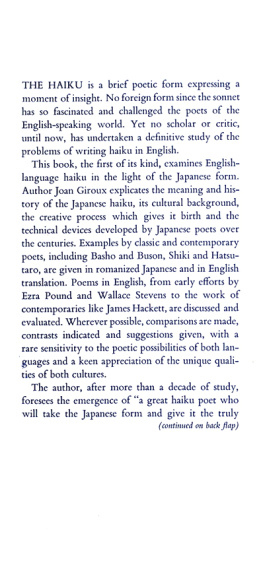

The haiku form Bash wrote in is now long familiar to Western readers: an image-based poem of seventeen sound units, written in lines of five, seven, and again five units each. (The Japanese on corresponds only approximately to our English syllable, though that word is generally used to translate it; in a similar issue, Japanese poetic lines are heard, rather than written with visually separate line breaks on the page, yet most English haiku translations are set, as here, into three-line form.) One further detail is widely known in the West: the poem must evoke a particular season, by name or association. Haiku is a welcoming form, taught often in elementary school classes. In a testament to both the limitlessness of any subject and the suppleness of haiku mind, over 19,000 haiku about SpamSpamkuhave to this date been posted online. Yet to write or read with only this understanding is to go back to what haiku was before Bash transformed it: playful verse is the words literal meaning. Bash asked more: to make of this brief, buoyant verse-tool the kinds of emotional, psychological and spiritual discoveries that he experienced in the work of earlier poets. He wanted to renovate human vision by putting what he saw into a bare handful of mostly ordinary words, and he wanted to renovate language by what he asked it to see.

Aging announced by the sensitivity of failing teeth; a street entertainers monkey; natural world phenomena; subtle examinations of mind and feelingseach is conveyed in Bashs haiku by what seems a single motion of the ink brush:

growing old:

eating seaweed,

teeth hitting sand

otoroiya ha ni kui ateshi nori no suna

first winter downpour:

the street monkey, too,

seems to look for his small straw raincoat

hatsushigure saru mo ko mino o hoshi ge nari

seas darkening,

the wild ducks calls

grow faintly white

umikure te kamo no koe honoka ni shiroshi

the crescent moon:

it also resembles

nothing

nanigoto no mitate ni mo ni zu mika no tsuki

even in Kyoto,

hearing a cuckoo,

I long for Kyoto

kynite mo ky natsukashi ya hototogisu

Bashs haiku, taken as a whole, conduct an extended investigation into how much can be said and known by image. When the space between poet and object disappears, Bash taught, the object itself can begin to be fully perceived. Through this transparent seeing, our own existence is made larger. Plants, stones, utensils, each thing has its individual feelings, similar to those of men, Bash wrote. The statement foreshadows by three centuries T.S. Eliots theory of the objective correlative: that the description of particular objects will evoke in us corresponding emotions.

The imagist aesthetic introduced to Western poetry near the start of the 20th century by Ezra Pound, Amy Lowell, William Carlos Williams, and Eliot is so deeply part of current poetics that few recognize its historical origins in Asia. Haiku in its strict form has continued to draw many American contemporary writers as well, from the poet Richard Wilbur to the novelist Richard Wright, who wrote thousands of haiku during his final years. One magnet is the paradox of haikus scale and speed. In the moment of haiku perception, something outer is seen, heard, tasted, felt, emplaced in a scene or context. That new perception then seeds an inner response beyond paraphrase, name, or any other form of containment.

Here is one such poem, seated in objective perception:

dusk: bells quiet,

fragrance rings

night-struck from flowers

kanekiete hana no ka wa tsuku ybe kana

This poem lives almost entirely in the ears and the nose, in perception both outward and accuratethe scent of certain blossoming trees does strengthen at nightfall, and orange trees (strongly night-scented) surround the temple at Ueno, where the haiku was written. The words show Bashs characteristic synaesthesia: bell-sound and twilight, flower-scent and time, are painted together into the mind, placed into a relationship that seems neither sequential nor causative. This haikus emotion cannot be defined except by repeating its own words; its center of gravity lies in the phenomenal world, outside the self. Yet it carries the scent and weight of strong feeling.