Table of Contents

Guide

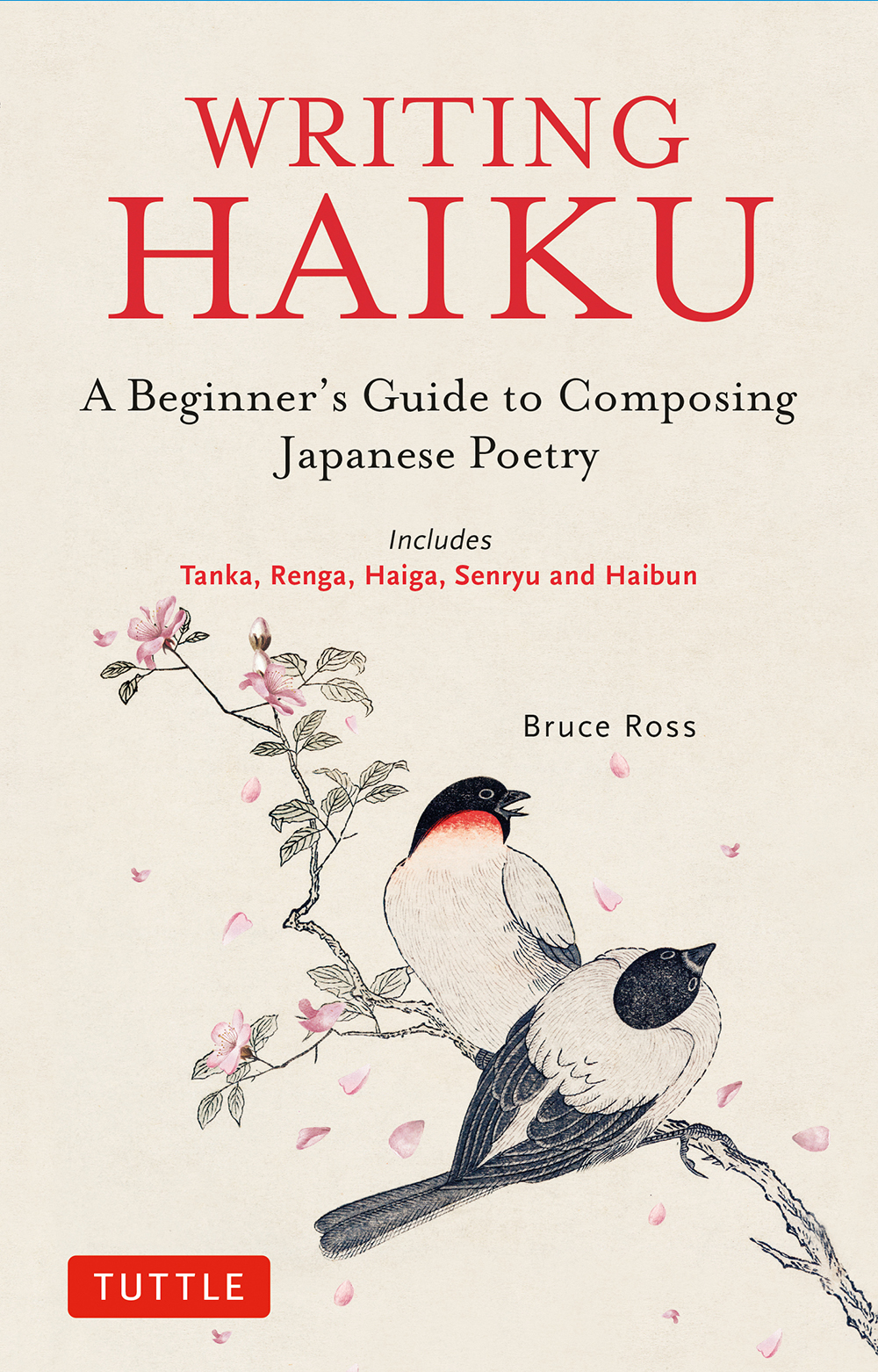

WRITING

HAIKU

A Beginners Guide to Composing

Japanese Haiku Poetry

Bruce Ross

Contents

To my friends in the world haiku community

A thousand bows to you.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my students at Writers & Books, Rochester,

New York; Writers at Champlain Mill, Winooski, Vermont; the

Institute on Japan of the University of Vermont; the Doll-Anstadt

Gallery, Burlington, Vermont; and the Japan-America Society of

Vermont. Also, the comembers of the Haiku Poets of Upstate New

York and the Burlington Haiku Group. And, finally, those haiku po

ets met in activities sponsored by Haiku Canada, the Haiku Society

of America, the Boston Haiku Society, the Kaji Aso Studio, Boston,

Massachusetts, and Haiku North America. Thanks for assistance

are due to Francine Porad, John Stevenson, and Tomiko Hayashi.

Thanks also are due to my editor, Jan Johnson, for nudging me in

the right direction. Lastly, and most importantly, Astrid Calypso

Miriam Andreescu, my wife; Murray David Ross, my brother; and

Tom Clausen, my friend, well deserve very special thanks.

Foreword to the

Second Edition

It has been nineteen years since I published the first edition of

this book. Since then, there have been two major changes in the

haiku world. The first major change is a worldwide interest and

production of haiku in other languages. For example, here is an

award-winning haiku from Goran Gatalica from Croatia, including

the original version in Croatian.

spring pilgrimage

first cherry blossoms

in mothers sandals

proljetno hodoae

prvi cvjetovi trenje

u majinim sandalama

The second major change began in the United States, and represents

a change in phrasing and word choice, perhaps resulting from com

puter and smartphone use.

However, the haiku form is timeless. Each individual haiku poet

has the ability to experience their own so-called haiku moment that

is a poetic insight.

I originally wrote this book as an easy-to-understand guide to

writing haiku and related forms for a young readership. My pub

lisher, Tuttle, wanted a revised edition of the book, but since haiku

is timeless, I have left the body of the book intact.

Bruce Ross, Hampden, Maine 2021

Introduction

ONE EVENING I WAS WATCHING a program about elderly peo

ple who had problems with their bones. As part of their treatment

they joined a class that practiced a form of Tai Chi, the oriental

exercise that has very slow and simple movements and looks like

slow-motion dance. The version for these patients was even simpler.

They stood straight up and moved their arms in a few easy patterns.

In a later interview, one of the patients told how she broke into a

sweat while doing the slow movements as if she had been playing

tennis like she used to. She then commented: Its very difficult to

do something small in a meaningful way.

Haiku is like that. It is perhaps the smallest poetry form in the

world, with about eight to twelve words in three short lines. Yet this

tiny poem can say important things about how we feel about what we

see around us. Haiku was invented hundreds of years ago in Japan.

It was used to express feelings about nature, animals, and the seasons

at a particular time and place and to share those feelings with others.

So to write a haiku means to write about how you feel at a certain

moment in time even if you are writing it down sometime after.

In the spring of 1999 the Burlington Haiku Group set up a

haiku table at the Japan-America Society of Vermonts Japanese

festival. A teenaged boy shrugged his shoulders when I asked him

if he wanted to try writing a haiku. But he sat down and drew an

empty couch to go with this haiku:

nothing happening

just another day

nothing happening

I am sure we have all had one of these days. But we may not have

been able to express this feeling as simply as this boy did. During

that same spring, the childrens librarian of Fletcher Free Library

in Burlington, Vermont, held a haiku writing workshop for kids.

Except for me and some mothers (to act as their childrens scribes),

all those who came to the workshop were kids seven to twelve years

old. One young girl wrote this haiku:

Birds in my backyard

they sing sing sing all day long

birds in my backyard

Another common experience: a bright spring day when the birds

keep up their cheerful singing all day long, colorful spring flowers

all around us. We know what the writer of this haiku felt.

Traditional Japanese haiku has two important parts. One is the

joining of two images where you are really comparing the relation

ship between the two. This comparison is not like those we find in

most poetry. We wouldnt say, He looks like a monkey in a haiku.

Instead, we try to show what our feelings are by putting something

we experienced together with another thing we experienced. We have

a bad day so nothing is happening. Or nothing is happening because

we are having a bad day. Tomorrow will probably be a better day. But

today is a bad day. The other important part of traditional Japanese

haiku is to connect our feelings to nature and the natural seasons.

If we find a snowman, a Halloween costume, spring flowers, or a

sandcastle in a haiku, we know what season that haiku is expressing.

We know how that season feels. So if we find a snowman in a haiku

we remember how winter feels. If birds are singing all day in a hai

ku, we know that it is spring, and we remember how spring feels.

Traditional Japanese haiku and all other haiku can express all

kinds of feelings. Here is a haiku by the Japanese poet who is said

to have created the haiku poem form:

stillness:

sinking into the rocks

a cicadas voice

Basho

We know from Bashos journal that he was traveling around Japan

when he wrote this. In summer he stopped to visit an ancient temple

on a high mountain. This temple was noted for its peacefulness.

Basho wrote that there was absolute silence when he visited and

that he was deeply moved by the experience. His haiku presents

us with his feeling. He first names the silence that is the most

important thing in this experience. The one sound, the crickets

chirp, makes the silence even greater. This small voice is powerful

because it is the only sound. But this small voice is absorbed by

the stillness of the rocks of the mountain and by the silence of the

temple. Compare the kind of feeling in Bashos haiku to one by an

American haiku poet:

Christmas Eve

at the lot, the trees

not chosen

Tom Tico

We all know the happiness of being with our families on Christ

mas Eve. Almost everyone is at home relaxing with a festive meal and

the promise of gifts. We are also supposed to feel goodwill toward

everyone. But for one reason or another some people are left out

of this celebration. The leftover Christmas trees remind us of those

people. This haiku leaves us with a deep feeling of sadness by con

necting this holiday night of expectation, celebration, and reverence

to an image of something left out.

Haiku can also offer a playful feeling. Here is another cricket