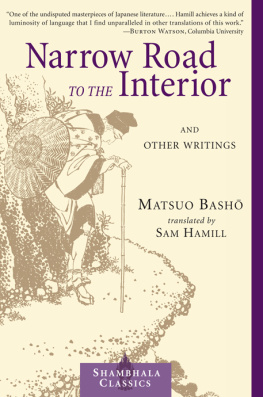

BASHO, the Japanese poet and diarist, was born in Iga-ueno near Kyoto in 1644. He spent his youth as companion to the son of the local lord, and with him he studied the writing of seventeen-syllable verse. In 1667 he moved to Edo (now Tokyo) where he continued to write verse. He eventually became a recluse, living on the outskirts of Edo in a hut. When he travelled he relied entirely on the hospitality of temples and fellow-poets. In his writings he was strongly influenced by the Zen sect of Buddhism.

On Love

and Barley:

Haiku

of Basho

Translated from

the Japanese

with an Introduction by

Lucien Stryk

Penguin Books

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published 1985

22

Copyright Lucien Stryk, 1985

All rights reserved

The illustrations are from an album of paintings by Taiga, reproduced

by kind permission of the Trustees of the British Museum

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject

to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent,

re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers

prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in

which it is published and without a similar condition including this

condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

EISBN: 9780141907772

To Hiroshi Takaoka with affection

Contents

Introduction

It is night: imagine, if you will, a path leading to a hut lost in a wildly growing arbour, shaded by the basho, a wide-leafed banana tree rare to Japan. A sliding door opens: an eager-eyed man in monks robe steps out, surveys his shadowy thicket and the purple outline of a distant mountain, bends his head to catch the rush of river just beyond; then, looking up at the sky, pauses a while, and claps his hands. Three hundred years pass the voice remains fresh and exciting as that moment.

Summer moon

clapping hands,

I herald dawn.

So it was with Matsuo Kinsaku (164494), the first great haiku poet, who would later change his name to Basho in honour of the tree given him by a disciple.

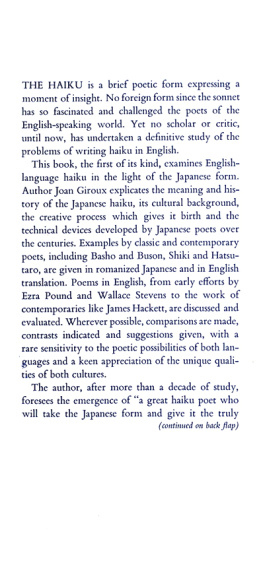

Basho appeared on the scene soon after the so-called Dark Age of Japanese literature (14251625), a time of the popularization of purely indigenous verse forms, and the brilliant beginning of the Tokugawa era (16031867). The haiku was already well established, with its own distinct rules, but in the hands of rule-smiths (as in the sonnet of Western verse) it was expiring of artificiality. Almost alone, Basho reinvigorated the form. How he did so is, fortunately, well known, for among his many admirers were a few far-seeing enough to record his comments, literally to catch him on the run, for he was always a compulsive traveller, wandering all over Japan in search of new sights and experiences.

He wrote at least one thousand haiku, as well as a number of travel sketches, which contain some of his finest poems. One of the sketches, The Records of a Travel-Worn Satchel, begins with a most revealing account of what poetry meant to him:

In this poor body, composed of one hundred bones and nine openings, is something called spirit, a flimsy curtain swept this way and that by the slightest breeze. It is spirit, such as it is, which led me to poetry, at first little more than a pastime, then the full business of my life. There have been times when my spirit, so dejected, almost gave up the quest, other times when it was proud, triumphant. So it has been from the very start, never finding peace with itself, always doubting the worth of what it makes All who achieve greatness in art Saigyo in traditional poetry, Sogi in linked verse, Sesshu in painting, Rikyu in tea ceremony possess one thing in common: they are one with nature.

Towards the end of his life Basho cautioned fellow haiku poets to rid their minds of superficiality by means of what he called karumi (lightness). This quality, so important to all arts linked to Zen (Basho had become a monk), is the artistic expression of non-attachment, the result of calm realization of profoundly felt truths. Here, from a preface to one of his works, is how the poet pictures karumi: In my view a good poem is one in which the form of the verse, and the joining of its two parts, seem light as a shallow river flowing over its sandy bed.

Bashos mature haiku style, Shofu, is known not only for karumi, but also for two other Zen-inspired aesthetic ideals: sabi and wabi. Sabi implies contented solitariness, and in Zen is associated with early monastic experience, when a high degree of detachment is cultivated. Wabi can be described as the spirit of poverty, an appreciation of the commonplace, and is perhaps most fully achieved in the tea ceremony, which, from the simple utensils used in the preparation of the tea to the very structure of the tea hut, honours the humble.

Basho perceived, early in his career, that the first haiku writers, among them Sokan (14581546) and Moritake (14721549), while historically of much importance, had little to offer poets of his day. These early writers had created the haiku form by establishing the autonomy of the parts of haikai renga, sequences of seventeen-syllable verses composed by poets working together. Though their poems possessed the desired terseness, they did not adequately evoke nature and, for the most part, lacked karumi. Basho wove his poems so closely around this feeling of lightness that at times he dared ignore time-honoured elements of the form, including the syllabic limitation. The following piece, among his greatest, consists in the original of eighteen syllables: