Published by

Stone Bridge Press, P.O, Box 8208, Berkeley, CA 94707

510-524-8732

Cover design by Linda Thurston.

Text design by Peter Goodman.

Text copyright 1996 by Hiroaki Sato.

Signature of the author on front part-title page: Bash.

Illustrations by Yosa Buson reproduced by permission of Itsu Museum.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

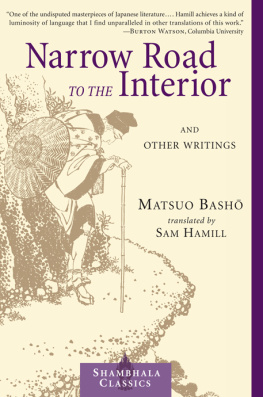

Matsuo, Bash, 16441694.

[Oku no hosomichi. English]

Bashs Narrow road: spring and autumn passages: two works / by Matsuo Bash: translated from the Japanese, with annotations by Hiroaki Sato.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Contents: Narrow road to the interior and the renga sequenceA farewell gift to Sora.

ISBN 9781880656205 (pbk.)

1. Matsuo, Bash, 16441694JourneysJapan. 2. JapanDescription and travelEarly works to 1800. 3. Authors, JapaneseEdo period, 16001868JourneysJapan. I. Sat, Hiroaki, 1942. II. Matsuo, Bash, 16441694. Sora sen. English. III. Title.

PL794.4.Z5A3613 1996

895.6132dc20

96-4392

CIP

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO

Miss Eleanor Wolff

(September 23, 1907October 26, 1995)

Doris Bargen

FOREWORD

CARRYING A PACK WITH HIS WRITING MATERIALS, A FEW pieces of clothing, and several gifts from friends who saw him off, the poet Bash set out on a hike to the wilds of northern Honsh in the spring of 1689. With his close disciple Sora, he planned to visit places famous as wonders of nature or significant in literary, religious, or military historyand he wanted to spread to the poetry lovers he would meet in the towns and villages along the way his methods of writing renga, the communal linked verse that was his passion and greatest concern in life.

The account he wrote of that trip, and which he revised and polished for four years, is one of the masterpieces of Japanese literature. Called Oku no Hosomichi, this travel diary is in a genre called haibuna mixture of haiku-like prose and haiku. Though he had done a number of shorter works in this genreabout other travels, places he had lived, and people he had knownthis was his longest and best. He died not long after he finished it, while on still another journey.

The work is shorter than many Western novellas: a small pond compared with the vast ocean of Lady Murasakis eleventh-century novel Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji), another major constellation in Japans literary firmament. But it is smaller only in size. In fact, part of its greatness lies in its doing so much with so little. Like a haiku it gets its vivid immediacy and sensory power from the suggestiveness created by its terse, laconic style. It is all at once a travel journal (kikbun), a haibun, a renga, and a haiku anthology. Bash deliberately shaped it this waychanging the order of some of the events and even inventing someto make it a work of art.

It follows the general form of Bashs style of renga (known as haikai no renga): from the slow, low-key introduction to the varied development of the middle part to the fast close of the finale. Though it is more unified and thematic than renga, it still has many surprising renga-like juxtapositions provided by places and eventsnot only those he experienced or invented, but also many he evokes from allusions to or quotations from historical, literary, and mythical sources. These elements move in and out of the prose and haiku.

One could even describe this haibun as a series of about fifty short haibun which work with each other much like the links in a renga. The haiku themselves present a varied array that also moves from subject to subject in the disjunctive manner of renga: from the hidden blossoms of a chestnut growing close to the eaves, to the ghostly dreams of dead warriors in the summer grass, to the poet trying to sleep while lying next to a pissing horse, to the rain-flooded Mogami River, a faint moon over Mount Haguro, the Milky Way over a rough ocean, and the cry of a cricket coming from under an ancient helmet in a provincial shrine.

Haiku, then known as hokku, were just beginning to be treated as separate poems around Bashs time. Before that they were each simply the beginning link of a renga. Paradoxically, since they could now exist as poems separate from the renga, they could also now be combined with prose to create haibun. There was a centuries-old precedent for this. The tankaa poem almost twice as long as a haiku, thirty-one syllables versus seventeenhad long been combined with prose in various kinds of literary works. Genji, which mixes eight hundred tanka with its prose, is only one of countless examples of stories, tales, and travel diaries that combined poetry with prose before Bash. Haibun can refer to the haiku-style prose by itself, and haiku poets sometimes write haibun without any haiku.

Bash had been developing his haiku and his travel-journal haibun for a number of years. His earlier haibun, such as Nozarashi Kik, tend to have the haiku just tacked on to the prose; the two are not integrated and working together. Nor is the prose as developed into a haiku style as in his later works. The combining of haiku and prose into a totally unified work of art found its culmination in the Oku.

In this remarkable translation by Hiroaki Sato, we find the elliptical, allusive, suggestive richness of the original brought over into English. The idiosyncratic lightness of style combined with the passionate intensity of love evinced by Bash for past poets and their poetry, the exploits of legendary gods, goddesses, heroes and heroines and the places hallowed by their deeds or presence, and the natural wonders of the land all come alive in this new translation. Without Bashs knowledge of the literary, legendary, and real history of Japan, we may not recognize what, for us, is locked up in the Oku. This is where Mr. Satos annotations step in and unlock and shed light on many of the innumerable references Bash has packed into his work. They work together with the translation to make this the most accessible version in English.

The annotations not only reveal the many allusions to earlier works but present us with the works themselves, for Mr. Sato has added them, or excerpts, to many of these notes in both Japanese transliteration and in English translation. He also gives us the continuations of a number of the renga Bash participated in on this journey, where in the haibun itself the poet has given us only the opening hokku. These added links elucidate Bashs linking techniques and give us a sense of the renga parties he took part in by indicating the interplay between the poets. All of these notes (footnotes and endnotes) open up the whole work like a program in a computer opens windows in one part of a file into other related files, and from those into still others. We can follow many of the threads Bash used in his work back to their original sources and then back again to see how he wove them into his own unique creation.

One of the most rewarding of these avenues, threads, or files, that stream from and into the original Oku no Hosomichi is Mr. Satos complete translation, with commentary, of A Farewell Gift to Sora, a renga written toward the end of the journey by Bash, Sora, and Hokushi. It retains various links they considered, discussed, and rejected, along with many of Bashs comments on these and on the accepted links, and on writing renga in general. So we have the Oku branching out to the Gift branching out to the picture we get of the poets sitting together writing the renga.