On the Narrow Road to the Deep North

Leslie Downer

Lesley Downer, 1989

Leslie Downer has asserted her rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

First published in 1989 by Jonathan Cape Ltd

This edition published in 2015 by Endeavour Press Ltd.

For my mother and father

Table of Contents

Introduction

This year, the second year of Genroku, I have decided to make a long walking trip to the distant provinces of the far north. Though the hardships of the journey will pile up snowy hairs on my head, I will see with my own eyes remote places of which I have only heard I cannot even be certain that I will return alive.

It was a fine spring morning when the poet Matsuo Basho set out on this last long journey of his, to the wild north of Japan. The sky was hazy and the moon still faintly visible. From Fukagawa, on the outskirts of Edo (old Tokyo), he could see Mount Fuji in the far distance, its perfect cone etched against the morning sky and, closer at hand, the hills of Ueno and Yanaka, covered in pink cherry blossom. Heavy of heart, I wondered when I would see them again, he wrote.

He had so little expectation of ever returning that he had sold his house in Fukagawa. He made few preparations for the journey patched his trousers, put new cords on his hat, had moxa treatment on his legs to make them stronger and took little more than the clothes on his back (plus a paper coat to protect me in the evening, yukata , rainwear, ink, brushes.)

His closest friends and disciples were there to see him off. They boarded the boat together and went with him the few miles up the Sumida river through the suburbs of Edo to Senju, where they disembarked. Here they said their farewells and Basho set off along the great highway to the north, accompanied only by one friend and companion, Kawai Sora. His disciples stood watching and waving until the small black-clad figures disappeared from sight.

My heart was overwhelmed at the thought of the three thousand ri that lay ahead, and as we separated, perhaps for ever, in this illusory world, I wept he wrote, and added a haiku

yuku haru ya

tori naki uo no

me wa namida

Spring passes!

Birds cry,

Fish have tears in their eyes

It was the twenty-seventh day of the third month by the old lunar calendar, May 16th 1689. The Stuarts had just lost their throne to William of Orange; Milton had died a few years before; Louis XIV was ruling from Versailles; and Newton had discovered gravity. In Japan, there was peace for the first time in centuries, which meant that the roads were safe for travellers, and poetry and the arts were flourishing. Thanks to the strong rule of the Tokugawa shoguns, the country was enjoying a renaissance; and Matsuo Basho was one of its leaders.

Basho was on the road for five months, a hard journey for a man who, at forty-five, already felt old and frail. There are many drawings and paintings of him from that time. He has a crumpled, kindly face, rather gaunt, a little greying stubble around his chin and tired eyes that gaze into the far distance. He dresses like a priest in black robes and flat cap, and carries a bamboo staff and wide-brimmed sedge hat.

Like a priest, he owned nothing. (He was never ordained, but, in the tradition of the wandering philosopher-poet, was, as he put it, not a priest nor a layman but more like a bat, wavering between bird and rat.) Wherever he went his disciples and admirers welcomed him, offered him hospitality, showed him their poems for correction and organised gatherings where they all sat down together to write poetry.

In this fashion Basho travelled, visiting local poets and places which had inspired poets in the past. For six weeks he walked the Oshukaido, the great north road through the eastern coastal plain, up into the remote province of Oshu.

Then he turned inland, into steep and rugged mountain country where often the forests were so thick that we couldnt hear one bird cry, and under the trees it was so dark that it was like walking at midnight. Sometimes he found nowhere better to stay than a stable; and at times he was afraid for his life. But it was also in these backward regions, as far as it was possible to be from the cultured world of Edo, that he had some of his strangest and most moving encounters. Finally the climax of the journey he met the near-legendary yamabushi, the hermit priests of the northern mountains; and spent a week with them at their sanctuary.

The final part of the journey was also the hardest: a walk of two and a half months, through the heat of the summer, along the Hokurikudo, the highway which led back down the western Japan Sea coast, ending at the town of Ogaki on October 18th.

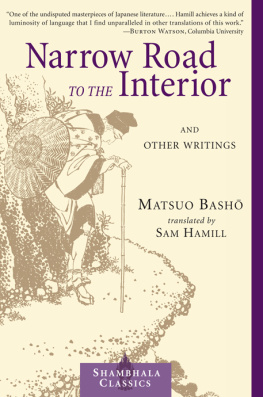

For the next four years Basho mulled over his experiences. Then he produced a book which he called Oku no hoso - michi ; oku means the interior, the back country, the northern provinces (the title for someone elses wife is Oku - san , Honourable Interior, Honourable Person-at-the-back); hoso is narrow, michi road or roads. In English its most famous and evocative title is The Narrow Road to the Deep North .

Nearly three hundred years have passed 1989 will be the 300th anniversary of Bashos journey. Basho is now admired as Japans greatest poet, as familiar a name in Japan as Shakespeare is in the West. The Narrow Road to the Deep North is on the curriculum of every school; and every Japanese (and many non-Japanese too) knows and loves his haiku.

Before I reached Japan I had come across the haiku and pondered over the syllables of the most famous

furu-ike ya

kawazu tobi-komu

mizu no oto

There are many translations; the one which I first read was in the Penguin edition of Basho

Breaking the silence

Of an ancient pond

A frog jumped into water

A deep resonance

The original is much more compact (and does not include the words a deep resonance hardly an appropriate expression for the sound of a frog jumping into water). Translated as near as possible word for word, it runs

Old pond

Frog jumps in

Sound of water

A picture, a happening, a sound and many profound philosophical ripples.

When I was a child I loved to look at Hokusais woodblock prints, the Thirty - six Views of Mount Fuji , at the lines of tiny figures with their straw hats and staffs, endlessly struggling across a stylised landscape of wild crags and thread-like bridges, with Fuji ever present in the background.

It was not until years later that I decided to go to Japan, attracted first by its pottery and later by its food and Buddhist culture, and began to learn the language. Somehow it never occurred to me to doubt my first images of the place. The Narrow Road and the other books I read only confirmed them. As a result, when I finally went there, I was as ill-prepared for a country of neon and high-rise blocks as anyone could ever be.

It was 1978.1 had taken a job as a teacher in a girls university in the provincial city of Gifu. There, far removed from Tokyo and its foreign enclaves, I hoped to find real Japan, the Japan of my imaginings. Instead I found myself the only foreigner (I discovered five others a few months later) in a city of 400,000 Japanese, crammed into concrete houses stretching endlessly along streets lined with hoardings, shadowed with wires and cables.

Shortly after I settled in Gifu I was invited to Iga Ueno. Hisae Tsuji had read about me in the paper (the novelty of my arrival had been greeted by newspaper articles and TV interviews). There were no foreigners in Iga Ueno; and, as she told me later, she thought it would be good for her two small sons to meet one. In this way she hoped they might absorb a little English perhaps by some process of osmosis.

Her husband was less enthusiastic. They met me at the station after a train journey that took half a day, trundling around mountains and across gorges to a picturesque part of the country, not far from the old city of Nara. He was a surly unsmiling fellow. Unlike Basho, who was neither a priest nor a layman, he was both by profession a maths teacher, by heritage a priest. (This was not at all rare; I knew many people who had inherited a temple but also carried on a normal job.) Irrespective of his natural inclinations, it was his duty to maintain the temple where his mother still lived, and conduct the occasional funeral.

Next page