Lucid and engaging, this translation, a gift of careful attention, does not separate poetry from spiritual practice. Bash becomes our guide on the way of insight. Such is the magic for a fine translation. Margaret Gibson, Tricycle Sam Hamill achieves a kind of luminosity of language that I find unparalleled in other translations. Burton Watson ABOUT THE BOOK This is the most complete single-volume collection of the writings of one of the great luminaries of Asian literature. Bash (16441694)who elevated the haiku to an art form of utter simplicity and intense spiritual beautyis best known in the West as the author of Narrow Road to the Interior, a travel diary of linked prose and haiku that recounts his journey through the far northern provinces of Japan.

This volume includes a masterful translation of his celebrated work along with three other less well-known but important works: Travelogue of Weather-Beaten Bones, The Knapsack Notebook, and Sarashina Travelogue. There is also a selection of over two hundred fifty of Bashs finest haiku. In addition, the translator has provided an introduction detailing Bashs life and work and an essay on the art of haiku. BASH (16441694)the most revered poet of Japanese literatureis best known in the West as the author of Narrow Road to the Interior, a travel diary of his journey through northern Japan. Bash elevated the haiku to an art form of utter simplicity and intense spiritual beauty. His travel diaries of linked prose and haiku created a new genre of writing that inspired generations of Japanese poets.

SAM HAMILL has translated more than two dozen books from ancient Chinese, Japanese, Greek, Latin, and Estonian. He has published fourteen volumes of original poetry. He has been the recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Guggenheim Foundation, the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, and the Mellon Fund. He was awarded the Decoracin de la Universidad de Carabobo in Venezuela, the Lifetime Achievement Award in Poetry from Washington Poets Association, and the PEN American Freedom to Write Award. He cofounded and served as Editor at Copper Canyon Press for thirty-two years and is the Director of Poets Against War.  Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.  Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

NARROW ROAD

to the INTERIOR

and other writings Matsuo Bash TRANSLATED FROM THE JAPANESE by SAM HAMILL

Matsuo Bash TRANSLATED FROM THE JAPANESE by SAM HAMILL  SHAMBHALA BOSTON & LONDON 2012 Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com 1998 by Sam Hamill All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Matsuo, Bash, 16441694. Narrow road to the interior: and other writings/Matsuo Bash; translated from the Japanese by Sam Hamill. cm. cm.

SHAMBHALA BOSTON & LONDON 2012 Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com 1998 by Sam Hamill All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Matsuo, Bash, 16441694. Narrow road to the interior: and other writings/Matsuo Bash; translated from the Japanese by Sam Hamill. cm. cm.

Previous ed.: The essential Bash, 1999. Includes bibliographical references. Contents: Narrow road to the interiorTravelogue of weather-beaten bonesThe knapsack notebookSarashina travelogueSelected haiku. eISBN 978-0-8348-2493-5 ISBN 978-1-57062-716-3 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. I. I.

Matsuo, Bash, 16441694 Essential Bash. II. Hamill, Sam. III. Title. Series. Series.

PL 794.4.A24 2000 895.6132dc21 00-038786 To Gray Foster and Eron HamillAnd to Bill ODaly, Galen Garwood, Keida Yusuke,Christopher Yohmei Blasdel, and Peter TurnerCompanions along the Way The moon and sun are eternal travelers. Even the years wander on. A lifetime adrift in a boat or in old age leading a tired horse into the years, every day is a journey, and the journey itself is home. Bash: Oku-no-hosomichi B ASH ROSE LONG BEFORE DAWN, but even at such an early hour, he knew the day would grow rosy bright. It was spring, 1689. In Ueno and Yanaka, cherry trees were in full blossom, and hundreds of families would soon be strolling under their branches, lovers walking and speaking softly or not at all.

But it wasnt cherry blossoms that occupied his mind. He had long dreamed of crossing the Shirakawa Barrier into the mountainous heartlands of northern Honshu, the country called Okuthe interiorlying immediately to the north of the city of Sendai. He patched his old cotton trousers and repaired his straw hat. He placed his old thatched-roof hut in anothers care and moved several hundred feet down the road to the home of his disciple-patron, Mr. Sampu, making final preparations before embarkation. On the morning of May 16, dawn rose through a shimmering mist, Mount Fuji faintly visible on the horizon.

It was the beginning of the Genroku period, a time of relative peace under the Tokugawa shogunate. But travel is always dangerous. A devotee as well as a traveling companion, Bashs friend, Sora, would shave his head and don the robes of a Zen monk, a tactic that often proved helpful at well-guarded checkpoints. Bash had done so himself on previous journeys. Because of poor health, Bash carried extra nightwear in his pack along with his cotton robe or yukata, a raincoat, calligraphy supplies, and of course hanamuke, departure gifts from well-wishers, gifts he found impossible to leave behind. Bash himself would leave behind a number of gifts upon his death some five years later, among them a journal composed after this journey, his health again in decline, a journal made up in part of fiction or fancy.

But during the spring and summer of 1689, he walked and watched. And from early 1690 into 1694, Bash wrote and revised his travel diary, which is not a diary at all. Oku means within and farthest or dead-end place; hosomichi means path or narrow road. The no is prepositional. Oku-no-hosomichi: the narrow road within; the narrow way through the interior. Narrow Road to the Interior is much, much more than a poetic travel journal. Narrow Road to the Interior is much, much more than a poetic travel journal.

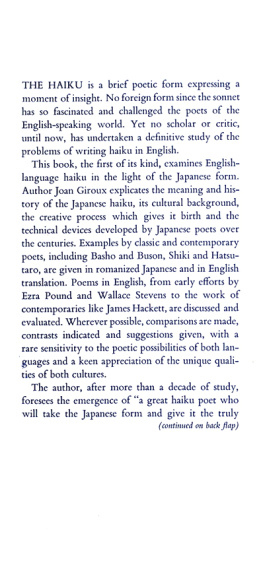

Its form, haibun, combines short prose passages with haiku. But the heart and mind of this little book, its kokoro, cannot be found simply by defining form. Bash completely redefined haiku and transformed haibun. These accomplishments grew out of arduous studies in poetry, Buddhism, history, Taoism, Confucianism, Shintoism, and some very important Zen training. Bash was a student of Saigy, a Buddhist monk-poet who lived five hundred years earlier (11181190), and who is the most prominent poet of the imperial anthology, Shinkokinsh. Like Saigy before him, Bash believed in co-dependent origination, a Buddhist idea holding that all things are fully interdependent, even at point of origin; that no thing is or can be completely self-originating.

Bash said of Saigy, He was obedient to and at one with nature and the four seasons. The Samantabhadra-bodhisattva-sutra says, Of one thing it is said, This is good, and of another it is said, This is bad, but there is nothing inherent in either to make them good or bad. The self is empty of independent existence. From Saigy, the poet learned the importance of being at one with nature, and the relative unimportance of mere personality. Such an attitude creates the Zen broth in which his poetry is steeped. Dreaming of the full moon as it rises over boats at Shiogama Beach, Bash is not looking outside himselfrather he is seeking that which is most clearly meaningful within, and locating the meaning within the context of juxtaposed images that are interpenetrating and interdependent.

Next page

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.  Matsuo Bash TRANSLATED FROM THE JAPANESE by SAM HAMILL

Matsuo Bash TRANSLATED FROM THE JAPANESE by SAM HAMILL  SHAMBHALA BOSTON & LONDON 2012 Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com 1998 by Sam Hamill All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Matsuo, Bash, 16441694. Narrow road to the interior: and other writings/Matsuo Bash; translated from the Japanese by Sam Hamill. cm. cm.

SHAMBHALA BOSTON & LONDON 2012 Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com 1998 by Sam Hamill All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Matsuo, Bash, 16441694. Narrow road to the interior: and other writings/Matsuo Bash; translated from the Japanese by Sam Hamill. cm. cm.