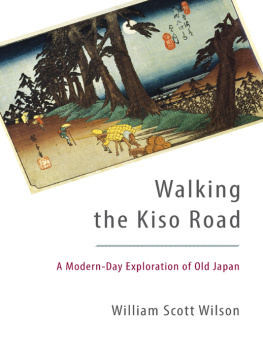

ABOUT THE BOOK

Take a trip to old Japan with William Scott Wilson as he travels the ancient Kiso Road, a legendary route that remains much the same today as it was hundreds of years ago. The Kisoji, which runs through the Kiso Valley in the Japanese Alps, has been in use since at least 701 C.E. In the seventeenth century, it was the route that the daimyo (warlords) used for their biennial tripsalong with their samurai and portersto the new capital of Edo (now Tokyo). The natural beauty of the route is renownedand famously inspired the landscapes of Hiroshige, as well as the work of many other artists and writers. Wilson, esteemed translator of samurai philosophy, has walked the road several times and is a delightful and expert guide to this popular tourist destination; he shares its rich history and lore, literary and artistic significance, cuisine and architecture, as well as his own experiences.

WILLIAM SCOTT WILSON is the foremost translator into English of traditional Japanese texts on samurai culture. He received BA degrees from Dartmouth College and the Monterey Institute of Foreign Studies, and an MA in Japanese literary studies from the University of Washington. His best-selling books include The Book of Five Rings, The Unfettered Mind, and The Lone Samurai, a biography of Miyamoto Musashi.

Sign up to receive news and special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

Walking the Kiso Road

A MODERN-DAY EXPLORATION OF OLD JAPAN

William Scott Wilson

Shambhala

BOSTON & LONDON | 2015

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

2015 by William Scott Wilson

Cover art: Mochizuki, from the series Sixty-nine Stages of the Kisokaido, by Utagawa Hiroshige, ca. 18351842.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLI CATION DATA

Wilson, William Scott, 1944

Walking the Kiso Road: a modern-day exploration of old Japan / William Scott Wilson.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN 978-0-8348-0317-6

ISBN 978-1-61180-125-5 (paperback)

1. Nakasendo (Japan)Description and travel. 2. Wilson, William Scott, 1944TravelJapanNakasendo. 3. Nakasendo (Japan)History. 4. Nakasendo (Japan)Social life and customs. I. Title.

DS894.59.N362W45 2015

952dc23

2015000280

For my son, Henry Clay Wilson

Contents

Broadly speaking, there are two kinds of map: the grid and the story. The grid map places an abstract geometric meshwork upon a space, within which any item or individual can be coordinated.... The power of grid maps is that they make it possible for any individual or object to be located within an abstract totality of space. But their virtue is also their danger: that they reduce the world only to data, that they record space independent of being. Story maps, by contrast, represent a place as it is perceived by an individual or by a culture. They are records of specific journeys, rather than describing place within which innumerable journeys might take place. They are organized around the passage of the traveler, and their perimeters are the perimeters of the sight or experience of the traveler. Event and place are not fully distinguished, for they are often of the same substance.

Robert Macfarlane, The Wild Places

A NUMBER OF YEARS AGO , I found myself seated comfortably on an early-morning local train heading out of the city of Nagoya. The train made a number of stops inside the city and then eventually moved on to the outskirts, passed the huge Oji Paper Company surrounded by its medieval-type walls, continued on with a stop now and then through farming communities with their rice and vegetable fields, and finally entered the low mountains bordering the broad, flat Nobi Plain. We paused briefly once or twice more to let people on or off at little unmanned stations and then moved on. It was early autumn, and the mountains were still predominantly green, but with some patches of fall colors and a persimmon tree covered with bright orange fruit here and there. Mists still hung in the folds of the low hills.

Finally, the train pulled into my stop, the village of Nagiso, tucked in almost like a narrow, quiet stream running through the valley, where I was informed that the minibus to my destination, Tsumago, would be leaving in two minutes. Grabbing my pack, I hurried out of the station and into a small parking lot where I purchased my ticket and got on board. Seconds later, we pulled out of the tiny village, moved out onto National Highway 17 (two lanes) and, following the Kiso River, drove through a hamlet or two and passed a large statuary company displaying granite grave markers and statues in various sizes of Buddhist saints, mysterious foxes, and some very large toads. Then, in less than fifteen minutes, we pulled into another small, open parking lot, where most of us got off.

There was nothing in particular to suggest that we had arrived at a very interesting place, but walking up through a narrow cobblestoned alleyway, I suddenly entered a village that had not changed much for two or three hundred years. Passed by the new (early twentieth century) railroad, it had missed the modernization that had brought other locales in the Kiso Valley almost up to date. The only street in town, the old Kiso Road, was extremely narrow and lined by shops, inns, and tiny restaurants where one could get not much more than a bowl of buckwheat noodles to eatall made of weathered but well-kept wood and clearly of some age. I had stepped, with my nice nylon rucksack and Gortex raincoat, back in time.

A friendly shopkeeper pointed out the inn, the Matsushiro-ya, where I had booked two nights lodgingagain, an entirely wooden two-story structure with large wood-slatted sliding paper doors and floor-to-ceiling open sliding windows that took up the entire front of the edifice. As I signed the register, the proprietora short, fiftyish man with short cropped hairinformed me that the inn was some three hundred fifty years old and that he was the eighteenth generation of innkeeper there. Everything in the Matsushiro-ya was as it had been, he said, except the toilets, some of which he had changed to the modern style to accommodate visitors from places like Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya. In the rooms, there were no televisions, no telephones, or anything electronic except for the lights, which had been installed, reluctantly, by his grandfather.

That night I was called down to dinner in a small room, my only companion a newspaper writer from Tokyo. Amid servings of river fish, mountain vegetables, grilled mushrooms, rice, and beer, we talked over our surroundings and made plans to walk over the pass to the post town of Magome the next morning. He would write a story about Tsumago and this short section of the Kiso Road upon his return.

The following morning, my new friend and I ate an early breakfast of fish, miso soup, vegetables, and rice, and then headed out for our hike. The innkeeper had kindly supplied us with the small bells travelers wear to scare off the black bears that inhabit the mountains; the weather was cool and the sky perfectly clear, and we chatted all along the pathagain, the old Kiso Roadup over the low but steep mountains, ringing our little bells in full faith and stopping to rest every thirty minutes or so. Much of the old road wound through dark cedar forests, the road itself often made of the original large, rough stones called

Next page