ABOUT THE BOOK

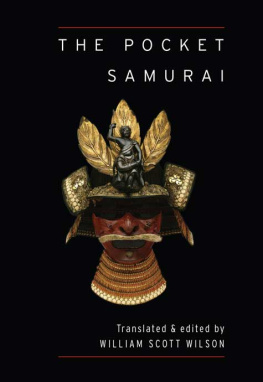

The samurai of Japan, who were the countrys military elite from medieval times to the end of the nineteenth century, were synonymous with valor, honor, and martial arts prowess. Their strict adherence to the code of bushido (the way of the warrior), chivalry, and honor in fighting to the death continues to capture the imagination of people today, inspiring authors, filmmakers, and artists. The Pocket Samurai contains the essential writings of the era by the most esteemed samurai and philosophers of the age, including the iconic Miyamoto Musashi, author of The Book of Five Rings; Yamamoto Tsunetomo, author of Hagakure, the best-known explication of the samurai code; Takuan Soho, a Zen priest and adviser to samurai; Yamaoka Tesshu, a master swordsman whose colorful life was devoted to martial arts and Zen; along with many others.

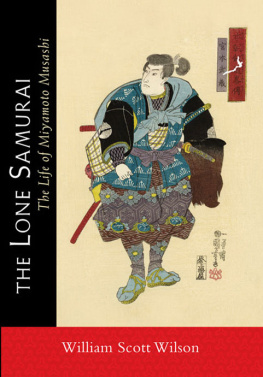

WILLIAM SCOTT WILSON is the foremost translator into English of traditional Japanese texts on samurai culture. He received BA degrees from Dartmouth College and the Monterey Institute of Foreign Studies, and an MA in Japanese literary studies from the University of Washington. His best-selling books include The Book of Five Rings, The Unfettered Mind, and The Lone Samurai, a biography of Miyamoto Musashi.

Sign up to receive news and special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

THE POCKET SAMURAI

Translated and edited by

William Scott Wilson

SHAMBHALA

Boston & London

2015

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

2015 by William Scott Wilson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The pocket samurai / translated and edited by

William Scott Wilson.First edition.

pages cm

eISBN 978-0-8348-3049-3

ISBN 978-1-61180-216-0 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. SamuraiConduct of life. 2. BushidoEarly works to 1800. 3. Military art and scienceHistoryJapan. I. Wilson, William Scott, 1944, translator, editor. II. Yamamoto, Tsunetomo, 16591719. Hagakure. English.

BJ971.B8P63 2015

952.025dc23

2014042270

The Way of the Samurai is found in death.

Hagakure

The Great Death is first and foremost, then comes rebirth.

Zen saying

Contents

(Hagakure)

(Wall Inscriptions)

(Budoshoshinshu)

(The Unfettered Mind)

(The Book of Five Rings)

(Cultivating Chi)

(Notes on Regulations )

(Kenzen wa)

(The Last Statementof Torii Mototada)

(Koyogunkan)

Publishers Note

This book contains diacritics and special characters. If you encounter difficulty displaying these characters, please set your e-reader device to publisher defaults (if available) or to an alternate font.

This book is a collection of works concerned with what it meant to be a samurai. All of the authors lived between the Warring States period (14821558) and the Edo period (16031868) but were broadly varied in status. Some were daimyo, or feudal lords; others were generals, philosophers, common warriors, ronin, and even a Zen Buddhist priest. Their commonality, however, is that they had all been born into the samurai, or warrior, class and thought deeply about what it meant to be a member of that class. As can be imagined, their responses to this question were as varied as their stations in life, but to find the single thread that runs through all of their observations, we must begin with the word itself.

The word samurai today is generally accepted to mean a warrior, but it is derived from the older word saburau, meaning simply to serve or attend. The first Chinese character used for this term was , which, according to the oldest records, indicated the various officers employed in a palace, regardless of their function. An even earlier Japanese term was samorau, written with the character , meaning to guard or protect, and indicated men who served an aristocrat by sitting at his right and left to protect him. This was, however, not simply defined by wearing a sword and engaging in combat.

Consider this story from the Hagakure.

Lord Somas family genealogy, called the Chiken marokashi, was the best in Japan. One year when his mansion suddenly caught fire and was burning to the ground, Lord Soma said, I feel no regret about the house and all its furnishings, even if they burn to the very last piece, because they are things that can be replaced later on. I only regret that I was unable to take out the genealogy, which is my familys most precious treasure.

There was one samurai among those attending him who said, I will go in and take it out. Lord Soma and the others all laughed and said, The house is already engulfed in flames. How are you going to take it out?

Now this man had never been loquacious, nor had he been particularly useful, but being a man who did things from beginning to end, he was engaged as an attendant. At this point he said, I have never been of use to my master because Im so careless, but I have lived resolved that someday my life should be of use to him. This seems to be that time. And he leapt into the flames.

After the fire had been extinguished, the master said, Look for his remains. What a pity! Looking everywhere, they found his burnt corpse in the garden adjacent to the living quarters. When they turned it over, blood flowed out of the stomach. The man had cut open his stomach and placed the genealogy inside and it was not damaged at all. From this time on it was called the Blood Genealogy.

Among the ideals shared by all samurai, the two most fundamental are exemplified by the nameless samurai in this well-known story. The first, muga ( ), or selflessness, is shared by both Confucianism and Zen (both important in samurai thought) but given different meanings.

In Confucianism, muga is considered to be the opposite of selfishness or self-centeredness. In the Analects, it is related that Confucius abstained from four things: willfulness, unreasonableness, attachment, and selfishness. The man who thinks in terms of his own livelihoodhis house, clothes, possessionsor places importance in his rank or power will be putting himself before his lord; his service to that man will take second place and eventually be sidetracked altogether. Thus, any true service must be done selflessly, or it is likely not to be done at all.

In Zen, this concept is taken religiously and psychologically, and means that, at the bedrock of our existence, there is no real self at all but only the illusion of such. Once we have truly come to this understanding, we have gone through the Great Death and are now capable of doing any act of service: the relative and unreal self is dead, and we have nothing to fear. This is perhaps what is meant by the Zen saying

A good thing [existence] cannot compare to nothing at all [nonexistence].

The second ideal, magokoro (), sincerity, is also shared by Confucianism and Zen, but it is in the former where it takes on a near mystical meaning. In the Doctrine of the Mean,

Next page