Foreword

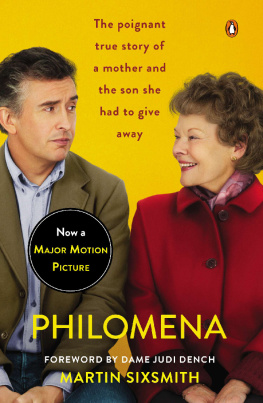

Philomena is the extraordinary story of an extraordinary woman. Philomena Lee was a naive teenager, whose only sin was to fall pregnant out of wedlock. Put away in a convent by an Irish society dominated by the Roman Catholic Church, she gave birth to a beautiful baby boy. For three years she cared for young Anthony, working all the while in the abbeys laundries. Then, like thousands of other fallen women, Philomena was forced to give up her child as a condition of being released from the near-slavery she found herself in.

This was the fate of many young mothers with illegitimate children in 1950s Ireland. Only very recently has the Irish government apologized for the living hell that was inflicted upon them. But Philomenas tale is special. This book, and the film that is based upon it, tells the story of her decades-long search for the son she lost. It depicts her uncertainty, hope and moments of despair. And at the end, it reveals a remarkable human being with astonishing fortitude and a truly humbling willingness to forgive. To me, it is astounding that Philomena still has her strong religious belief even after everything that was done to her. She questions things and is very open in speaking about her experiences, but her faith is unshakeable as strong as it always was.

When I was asked to play the part of Philomena in Stephen Frearss wonderful film, I thought back to my own Irish heritage. My mother was Irish, born in Dublin, and all her family were Irish. My father was born in Dorset, but went to Ireland with his parents when he was three. He grew up in Dublin and studied at Trinity College, as did all my cousins.

Although my mother was brought up a Methodist, she went to a Catholic school and I know she had fond memories of some of the nuns. Recognizing her faith, they excused her from Catholic prayers, and very sweetly gave her the job of dusting statues instead. My mother used to say she had the pleasant duty of keeping the Virgin Mary clean.

So I was pleased that Martin Sixsmiths book and Frearss film adaptation do not oversimplify the issues or paint the Catholic Church in an unremittingly black light. The role of the Church is, quite properly, examined, but care has been taken not to caricature what happened. These were different times. The system was a terrible one. But many of the nuns themselves were kind and not all the girls in their care were treated cruelly.

As was the case with most Irish people in the fifties and sixties, my family was unaware that this sort of thing was going on in Ireland. But Philomena was far from an isolated case. Innumerable mothers and children were torn apart, and many of them are still searching for each other, even now. It is terrible and very, very shocking. So I hope Philomenas heroic search and her courage in allowing her story to be told will bring comfort to all who have suffered a similar fate.

In making the film, I was conscious of the very real responsibility of playing a living person, and that weighed heavily on me. I felt very strongly that I was inhabiting the character of Philomena. It was a great challenge, but it was fantastic having Philomena herself to talk to; to be there as a reference when I needed her. It allowed me to understand the essence of the part in a way that was impossible when I played Elizabeth I, or Iris Murdoch, both of whom were long gone. It was also very rewarding for me to watch some of the scenes we had shot with Philomena sitting there beside me, her hand on my shoulder. I was extremely aware of her reaction to seeing the film and I watched her very closely when we got to the appearance of the boy actor who plays her lost son.

What I wanted more than anything was for the film to do her justice, and to do justice to Martin Sixsmiths book. I have worked with Stephen Frears as a director many times and I knew we were in safe hands. He has taken great care to remain true to Philomenas story, as well as to Martins book. I am so terribly glad to have done it. And I hope Philomena will be just as pleased with what we have made of her life story.

Dame Judi Dench, 2013

Prologue

The New Year of 2004 had come in. It was getting late and I was thinking of leaving the party was flat and I was tired but someone tapped my shoulder. The stranger was about forty-five and a little tipsy. She told me she was married to the brother of a mutual friend, but she wasnt planning to remain so much longer. I smiled politely. She put her hand on my arm and said she had something that might interest me.

Youre a journalist, arent you?

I used to be.

You can find things out, cant you?

It depends what they are.

You have to meet my friend. She has a puzzle she needs you to solve.

I was intrigued enough to meet the friend in the cafe of the British Library a financial administrator in her late thirties, smartly dressed with sharp blue eyes and jet-black hair. A family mystery was troubling her. Her mother, Philomena, had drunk too much sherry that Christmas and had broken down in tears. Shed had a secret to tell her family, a secret shed kept for fifty years...

Do we all yearn to be detectives? The conversation in the British Library was the start of a search that lasted five years and led me from London to Ireland and on to the United States. Old photographs, letters and diaries now litter my desk the hurried, anxious scrawl of an eager housewife, tearful signatures on sad documents and the image of a lost little boy in a blue jumper clutching a toy plane made of tin...

Everything that follows is true, or reconstructed to the best of my ability. There were clues to be found and no shortage of evidence. Some of the actors in the story kept diaries or left detailed correspondence; several are still alive and agreed to speak with me; others had confided their version of events to friends. Gaps have been filled, characters extrapolated and incidents surmised. But thats what detective work is all about, isnt it?

PART ONE

ONE

Saturday 5 July 1952;

Sean Ross Abbey, Roscrea, County Tipperary, Ireland

Sister Annunciata cursed the electric. Whenever there was thunder and lightning it flickered so desperate it was worse than the old paraffin lamps. And tonight they needed all the light they could get.

She was trying to run but her feet were catching in her habit and her hands were shaking. Hot water slopped from the enamel bowl onto the stone flags of the darkened corridor. It was all right for the others: all they had to do was pray to the Virgin, but Sister Annunciata was expected to do something practical: the girl was dying and no one had a clue how to save her.

In the makeshift surgery above the chapel, she knelt by the patient and whispered encouragement. The girl responded with a half-smile and something mumbled, incomprehensible. A lightning flash lit up the room. Annunciata pulled up the covers to shield the girl from the blood on the sheets.

Annunciata was barely older than her patient. Both of them were from the country; both from the depths of Limerick. But she was the birth sister and people were expecting her to do something.

In the chapel below, she could hear Mother Barbara gathering the girls, ordering them to pray for the Magdalene upstairs a sinner like them, who was dying. The disembodied voices sounded distant and harsh. Annunciata squeezed the girls hand and told her to take no notice. She lifted the patients white linen gown and wiped her legs with the warm water. The baby was visible now, but it was the childs back she could see, not the head. She had heard about breech births; another hour and she knew mother and baby would both be dead. The fever was setting in.