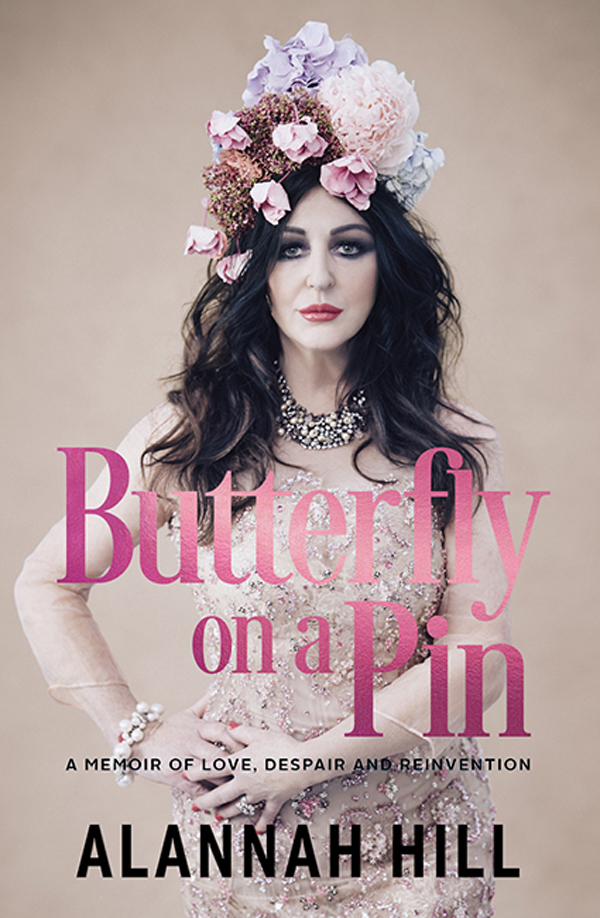

Our memories make up the ongoing experience of our lives and provide us with a sense of self. Your first kitten or pup, the sound of your babys first cries, the taste of your grandmothers sponge cake. These are memories that make us who we are. Our memories tie our pasts with our present and provide us with a framework for our future. I understand our memories are personal and that we all remember people, events and feelings differently. The events, people and places I have written about here are real and true memories for me. There are some instances where I have changed peoples names to protect their identity and privacy. Without memories, dear reader, we cease to exist.

Published in 2018 by Hardie Grant Books, an imprint of Hardie Grant Publishing

Hardie Grant Books (Melbourne)

Building 1, 658 Church Street

Richmond, Victoria 3121

Hardie Grant Books (London)

5th & 6th Floors

5254 Southwark Street

London SE1 1UN

hardiegrantbooks.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders.

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Copyright text Alannah Hill 2018

A catalogue record for this

book is available from the

National Library of Australia

Butterfly on a Pin

eISBN 9781743585580

| The paper this book is printed on is certified against the Forest Stewardship Council Standards. FSC promotes environmentally responsible, socially beneficial and economically viable management of the worlds forests. |

For Mum

CONTENTS

The day my mother attempted to kill herself was not like any other day Id known. I was five years old. I remember the darkening clouds gathering in the foothills of the small ghost town, a ghost town where my family lived, a ghost town in Tasmania called Geeveston.

I was desperately frightened.

My mother was very, very sick. She looked sick, she couldnt move her head, and in my rush to get to her I slipped on my own footsteps. Breathless, I crept quietly into her bleak and sombre bedroom. Mum was lying on her marital bed, staring at the ceiling, tears falling from her brown eyes, crawling down her face and onto her neck. I watched the chaotic mess and when the priests told me to get out, I couldnt. Somebody picked me up and dropped me onto the floor in the room next door where my three siblings were eating stale honey sandwiches. We began rocking backwards and forwards, backwards and forwards, humming my mothers favourite Catholic hymn: Nearer, my God, to Thee, nearer to Thee, nearer, my God, to Thee, nearer to Thee.

I couldnt hear my mum breathing. All I could hear was the sound of violent hiccups.

All we could do was rock back and forth, eating our honey sandwiches, waiting for the gigantic stranger, who was often seen glowering from corners or hurling raging aggression after drinking in the local pub. The stranger was my father.

A biblical hymn sounded from the marital bedroom and so my own hymn to God became even louder. I was shouting Nearer, my God, to Thee, shouting it with my stale honey sandwich trapped in my throat, rocking with my siblings in perfect timing, as my giant father arrived home with his imperfect timing. A flurry of noise, a farmers hat thrown onto the floor, boots thrown against a wall and there he was, my father: the man I believed was the reason Mum was lying on the marital bed in a state of Catholic exorcism.

I wanted to die. I wanted the whole world to die. My eyes were blurred from tears and I heard him shouting at my mum.

For Gods sake, Aileen. This again! Jesus, Mary and Joseph, Aileen, what the fuck do you want?

I knew even then what my mother wanted. I knew it and I never spoke up. I wondered why my father couldnt see it for himself.

The truth is that my mother, over a period of forty-five years, was almost sent mad by my fathers dismissal of her, and his own unhappiness, which, like the plague, spread death of one kind or another at a rate of a mile or more a day.

When I left Tasmania in 1979, I had never been on an aeroplane. Three decades later, it was not uncommon to find me in seat 1A, flying first class on one of Qantass fanciest new fleet of aeroplanes. Id be bound for London, Paris, New York City, Singapore and Tokyo trips that took in five cities in fourteen days. My bespoke sherbet-bomb diary was filled with high-flying career-girl fabric appointments, dinner invitations, posh fashion shows, art gallery openings and VIP tickets for Premire Vision, the famous Paris fabric and trim fair. I was chauffeured from the airport to a fancy boutique hotel.

Id climbed to the top of the mountain, climbed and climbed and climbed. Looking down from the clouds at my life in the broken-down houses of my childhood, Id wonder if it was all true. Did I really make it? I would immediately fret, thinking, God, if I lose this if my impossible dream gets taken from me I know Ill surely die. Id be overwhelmed by a sense of nothingness, the unjoined girl of my childhood never too far away.

My mother was always two dark steps ahead. Her superb wit always ready, always in waiting, to put a little two-bob snob like me in my place. To Mum, I would always be a sixteen-year-old runaway shopgirl. On my visits to Tasmania, she would often tell me of her desperate attempt to die, changing the time it had happened, the number of pills she swallowed, and why she was covered in a strange plum sauce.

I remember seeing priests hovering over your bed, Mum. Who looked after us? Why did Dad look so angry? Why, Mum, why? Tell me everything, Mum. Why, Mum?

Lan, what do you remember, dear? she would ask. You came home from the orchard coughing, coughing, coughing, coughing, remember that, Lan, I was in and out of consciousness, Lan, in and OUT of consciousness. You know I nearly died, dont you, Lan? You know you nearly lost me, dont you, Lan? You do realise I was almost DEAD, dont you, Lan? What a dreadful man I married a heathen, a philandering liar with insipid eyes. NO, I dont know why he didnt want you, Lan, I dont know why he wouldnt look at you! You were such a plain little thing. No personality, dear, you didnt have a speck of personality. Not a SPECK! You must have been frightened seeing your dear old mum lying on the marital bed DYING in front of your very own eyes, Lan. Dying! Right in front of your eyes, Lan!

Yes, dear reader, I was frightened, and the terror from my childhood has never left.

19621979

Even now I cant trust life.

It did too many awful things to me as a kid.

CLARA BOW, IT GIRL OF THE 30S

It was an early June morning in 1968. The trees were holding on to their dizzy green leaves leaves that would soon fall under the cold grey skies of the bitter Tasmanian winter. The beginning of each day seemed dead, almost forgotten, before it had even begun. The day would come to life midafternoon, only to die another lingering death until the new dawn woke the world up to reflect upon its forlorn, bewildered state.

There were four rooms in the apple orchard house where we lived in Scotts Road, Geeveston. My father, an orchardist, was asleep in a small cupboard area separated from the lounge room, loud snores blaring from beneath the newspaper he placed over his head to shut out the constant disappointment of the world he inhabited.