IMAGES

of America

SEATTLE RADIO

In 1941, KIRO became the first full-power 50,000-watt radio station west of Salt Lake City and north of San Francisco. Owner Saul Haas and chief engineer James B. Hatfield built this world-class transmitter facility on Maury Island. It was considered to be of national strategic importance during the war and was guarded by National Guard troops 24 hours a day. It was also the first directional antenna system built in the Northwest. Only one of KIROs two towers is seen in this image. (Courtesy of Hatfield and Dawson.)

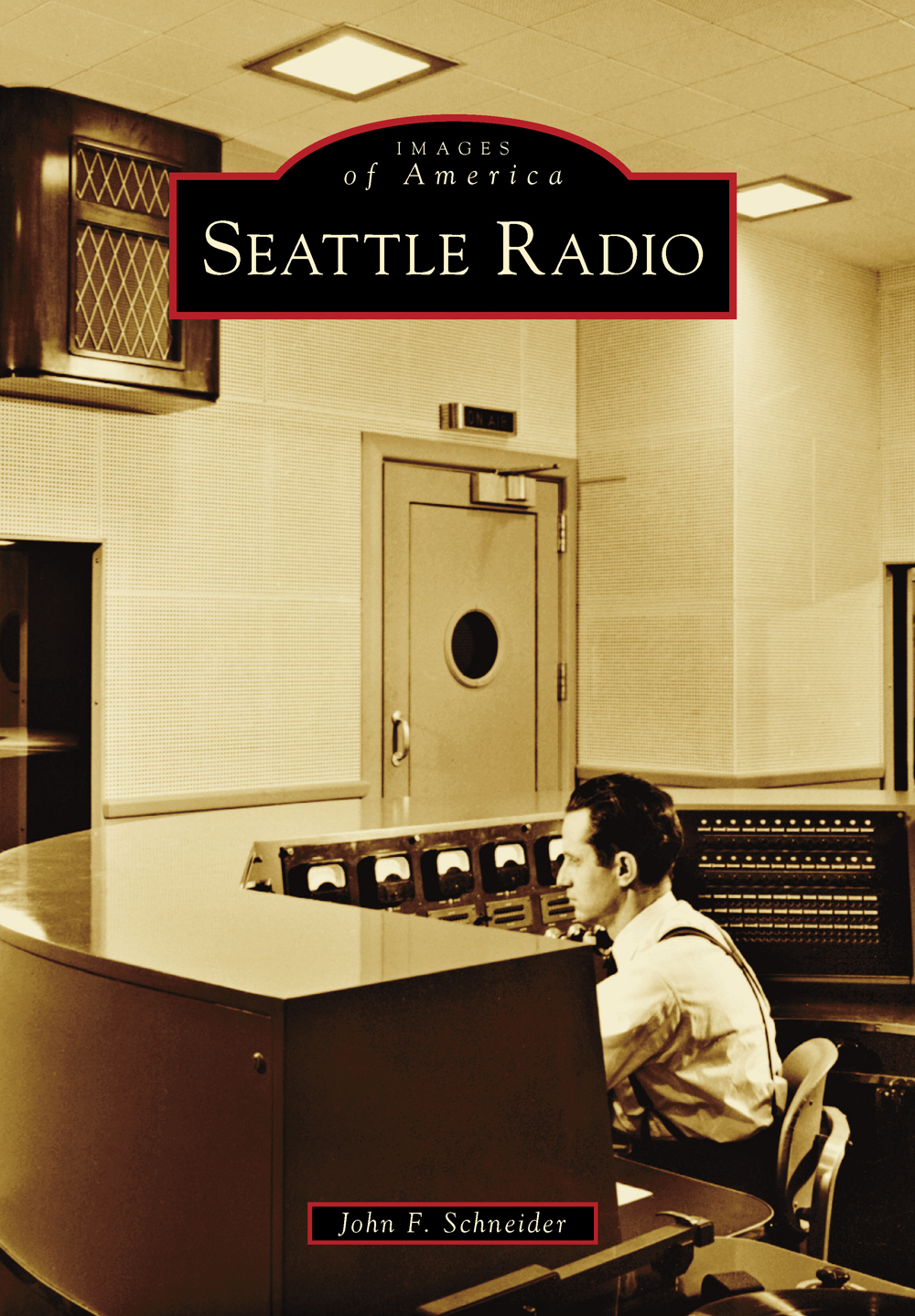

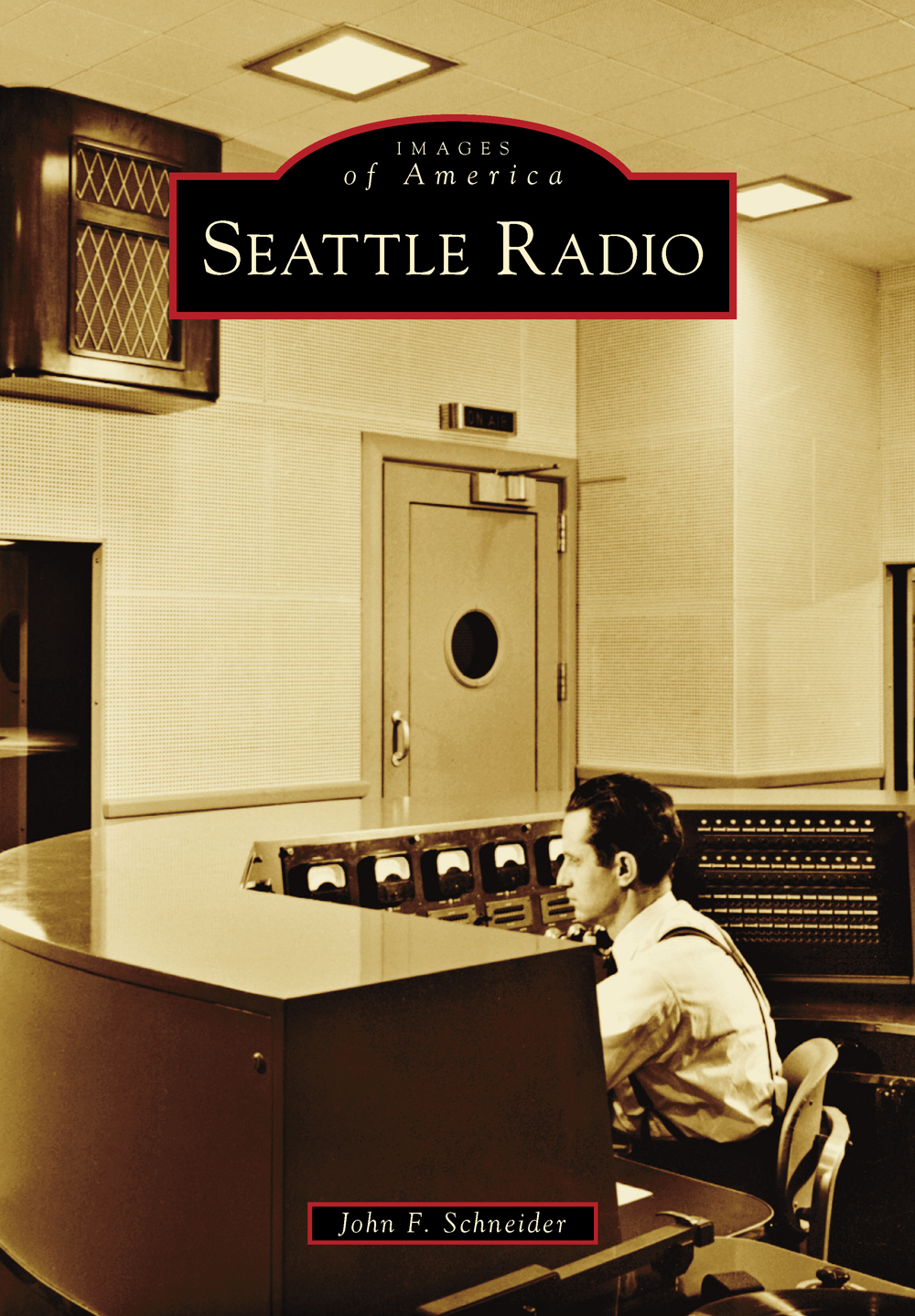

ON THE COVER: In 1948, KOMO opened Seattle radios most elaborate studio facility. Located at the corner of Fourth Avenue and Denny Way, it served as the source of KOMOs radio and television broadcasts for 40 years. This was the KOMO master control room when the building first opened. The audio from all studios came here, along with the NBC network and remote broadcast lines. The operator at this desk controlled everything that was heard on the air. (Courtesy of Jack Barnes.)

IMAGES

of America

SEATTLE RADIO

John F. Schneider

Copyright 2013 by John F. Schneider & Associates, LLC

ISBN 1-4671-3057-8

Ebook ISBN 9781439644270

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013935137

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

This book is dedicated to the Seattle Chapter No. 16 of the Society of Broadcast Engineers and the SBE members who supported me during its creation. I was honored to be the Seattle SBE chapter chairman from 1991 to 1993.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

As with any historical study, a lot of people contributed to this book. No one person has all of the information. The writer simply finds the people with the information and photographs and assembles it into a coherent story.

My involvement with the Seattle radio community was indirect. For 25 years, I ran a Seattle-area broadcast equipment sales business and dealt with most of the stations to support their technical needs. So, I observed Seattle radio from the sidelines, as a radio listener and as a friend of some participants, but I was not an expert on the subject. To prepare this book, I called on the support of many old friends and, in the process, made new friends. I also drew on information and photographs that I obtained decades ago from some of Seattles earliest broadcasters, most of whom are now manning the big radio towers in the sky.

This story of Seattle radio is incomplete. There is not enough space to tell the stories of the thousands of important people and events that passed in front of the Puget Sound microphones during almost 90 years. Additionally, being a photograph essay, the story must be told through images. Some important events were not photographed, and the images of many others have not survived the years. If you, a family member, or a favorite radio personality are not mentioned in this book, please accept my apologies. For further reading, find a copy of David Richardsons classic 1981 book Puget Sounds.

It is essential to recognize the many people and organizations that assisted me in telling this story, including Carol Arkell, Jack Barnes, Sonny Clutter, Dick Curtis, Ben Dawson, Chris Dubuque, Ron Edge, Clay Freinwald, Frosty Fowler, Jim French, Jim Hatfield, Kim Hunter, Ivars Restaurants, Walt Jamison, Nick Kerry, Howard Kraft, Christopher and Sandy Mael, Carolyn Marr (Museum of History & Industry), Gina Nelson, John Price, Homer Pope, Tom Read, Earl Reilly, Maia Santella, Andy Scotdal, Dwight Small, Bernice and Alex Smith, Bill Taylor, and George Walford.

I must also thank Alyssa Jones and the other professionals at Arcadia Publishing for their guidance in the creation of this work and for making it possible to bring you the story of Seattle radio.

John F. Schneider

May 2013

www.theradiohistorian.org

INTRODUCTION

Although experimental radio telephone transmissions in Seattleled by Lee de Forest, William Dubilier, and otherstook place as early as 1906, the consumer radio boom did not hit Seattle until the fall of 1921. By 1922, radio was all the rage.

Seattles first broadcaster was undoubtedly Vincent Kraft. He started broadcasting from the garage of his Ravenna home over his amateur station, 7XC, in 1919. He played phonograph and piano music through his 10-watt transmitter and single microphone. Other hams and early experimenters encouraged him to do more, and by March 1922, 7XC had been relicensed as KJR.

The citys second broadcaster was the Seattle Post-Intelligencers station KFC, transmitting from the roof of the P-I building at Sixth and Pine Streets. Carl Haymond was the program manager, announcer, engineer, and probably also the janitor. He led performers up the steep iron stairs to the roof and held a megaphone in front of the microphone while they sang or spoke into it.

Louis Wasmer started Seattles third station, KHQ, from his motorcycle shop on Thirteenth Avenue N. After increasing power, he sold his old transmitter to the Economy Market, where it went on the air as KZC. Rhodes Brothers Department Store put KDZE on the air in May 1922, and Seattle City Lights John D. Ross put KTW on the air for the First Presbyterian Church.

In the first two years, all of these stations, plus some latecomers, were required to share time on a single frequency360 meters (833 kilohertz)and listeners could only hear one station at a time. A station would broadcast for an hour and then shut down to be replaced by another station, stronger or weaker than the last one. The stations met with the local radio inspector periodically to work out an operating schedule.

Many of these early stations had poor audio quality and suffered continuous technical difficulties, and people soon tired of listening to scratchy broadcasts of phonograph records, so in 1924 the government established a second class of station. Class B stations operated with at least 500 watts and were prohibited from playing phonograph records. They were assigned their own exclusive frequencies and could operate more hours each day. The remaining stations continued to share 360 meters. The Rhodes stationby now known as KFOAwas Seattles first Class B station, assigned to the 660-kilohertz frequency. KJR and KTW later upgraded to Class B status as well.

As the decade progressed, many more stations were licensed, creating a glut. With just one channel available for most, there was no room for all to exist simultaneously. Many of these new stations were not serious efforts, only started by companies or individuals wanting to cash in on the radio boom. Many left the air within a year.

Roy Olmstead, Seattles biggest bootlegger, started KFQX from his Mount Baker home in 1924. That November, federal prohibition agents raided the home, shut down the radio station, and arrested Olmstead, who was convicted and sent to McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary. KFQX was then leased to Birt Fisher, who ran it as KTCL, but in 1926 Olmstead sold it to KJRs Vincent Kraft, who planned to take over the station when the lease expired in December. So, Fisher joined forces with the owners of the Fisher Flouring Mills Co. to open a new station, KOMO. Generously financed with a staff of 65 producing 14 hours of live programs a day, KOMO quickly became one of Seattles most popular stations; meanwhile, Vincent Kraft took over KTCL and turned it into KXA.

Next page