Harrison R. Crandall

Creating a Vision of Grand Teton National Park

Kenneth A. Barrick

Harrison R. Crandall

Creating a Vision of Grand Teton National Park

Digital Edition 1.0

Text 2013 Author

Photographs 2013 photographer

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except brief portions quoted for purpose of review.

Gibbs Smith

P.O. Box 667

Layton, Utah 84041

Orders: 1.800.835.4993

www.gibbs-smith.com

ISBN: 978-1-4236-3401-0

To the artists and photographers whose works inspired generations of Americans to love their national parksand to the national park officials that supported art in the parks.

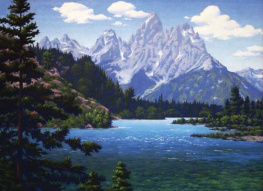

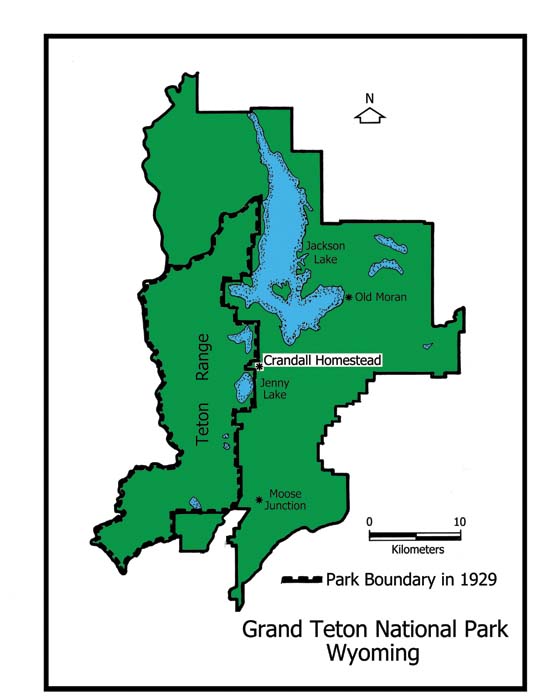

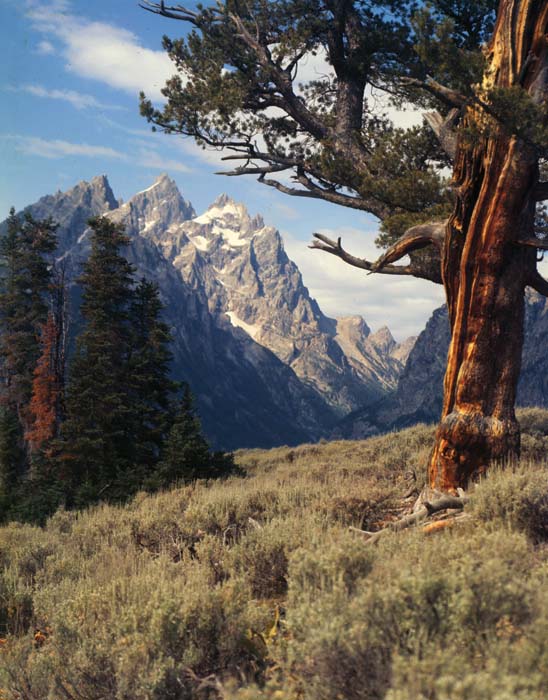

Plate 1. The Cathedral Group of peaks is framed by a towering tree. A color transparency. Photograph by H. R. Crandall, courtesy of Quita and Herb Pownall Collection.

Preface

You might be curious to know how a professor from Alaska became interested in Harrison R. Crandall, who preferred to be called Hank, and his role in creating a vision of Grand Teton National Park. As a geographer, I have a strong interest in landscape appreciation and how people interpret the meaning of national park art. I met Hank, through his art, 30 years after his death. In 1998 I attended an antique show in Bozeman, Montana, that specialized in the art of the national parks. Jack and Susan Davis hosted the show. The Davises are well-known experts on Yellowstone National Park antiques, and over the years they amassed the largest private collection of Yellowstone souvenirs and ephemera. A large part of the Davis collection was purchased by the Yellowstone Park Foundation for $500,000, and these important artifacts are now preserved at the Yellowstone Museum Collections, Archives, and Research Library.[] I attended the Davises show in my quest to complete a collection of Yellowstone photochroms, which are color lithographs made from black-and-white photographic negatives, taken by the famous American photographer William Henry Jackson (about 65 photochroms of Yellowstone were published in the United States by the Detroit Photographic Company between about 1898 and 1906).

My photochrom quest was not rewarded at the show, but I did find a different treasure! A local dealer was offering two splendid antique, hand-painted wildflower photographs (I spent 20 summers perfecting my own close-up photos of wildflowers, so I was not easily impressed). The wildflower pictures were embossed with the logo of Crandall from Teton Park. These were not just any wildflowersthey were the fringed gentian (the official flower of Yellowstone) and the wild rose (the only rose variety that is not eaten by the moose that visit my backyard). Moreover, these were not ordinary hand-painted photographs (hand coloring was a common technique that rendered color on photographs before the invention of color film). Hank Crandalls hand-painted photographs were uniquely overpainted with opaque oils, and the colors are bold and striking.

Collectors understand that it is important to remain focused on their subject, but my collection branched out that day. I did not hesitate to purchase those Crandall wildflower panels. I was intrigued about the artist, so I vowed to learn more. A few months later I had another lucky day when I discovered a large Crandall oil painting of Mount Moran (in the Teton Range) at an antique shop in Pennsylvania. The dealer had priced the painting without knowing its age, importance, or rarity. Collectors like to say that two or more of anything is a collectionand now I had several interesting examples of Hank Crandalls art.

However, I still did not know much about the artist. Detailed information was difficult to find. Therefore, with the encouragement of the curator at Grand Teton National Park and the surviving members of the Crandall family, I undertook a project to research Hanks biography and gather representative examples of his work. Little did I know at the time that this seemingly obscure pioneer from Teton country had secured a place as an important national park artist. Moreover, Hank Crandall had earned recognition as one of the luminaries of the national park preservation movementone of natures noblemen. Today we have the opportunity to appreciate Hanks timeless art and his familys pioneering contribution to Jackson Hole. I invite you to enjoy the story and the historic pictures, and I hope you will undertake a pilgrimage to Teton country in order to personally experience the mountain grandeur that gave Hank Crandall so much pleasure and inspiration.

[] Roger Anderson and Lee Whittlesey, Introduction to the Davis Collection, Yellowstone Science 9, no. 4 (2001): 1220. An interview with Susan and Jack Davis.

Introduction

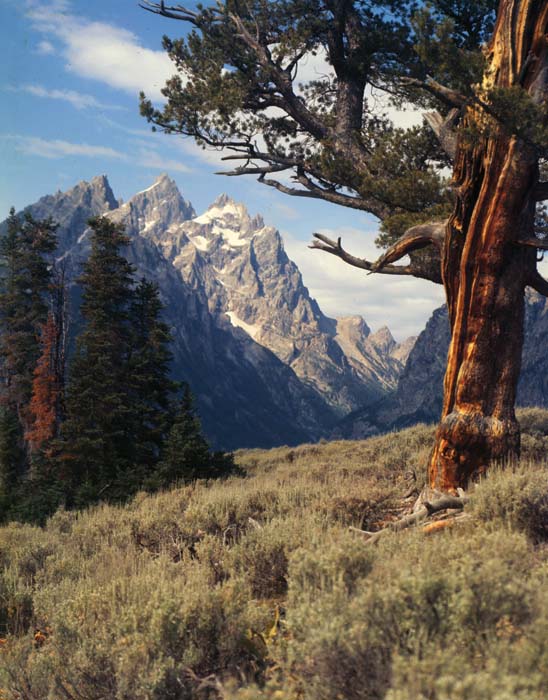

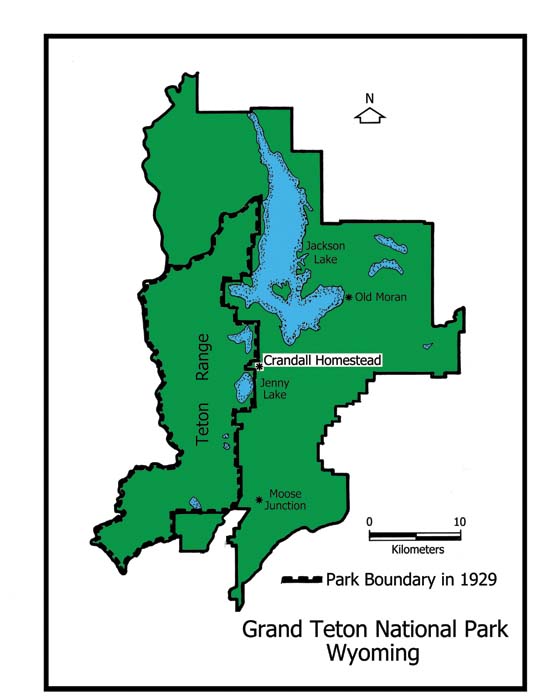

Harrison R. Hank Crandall (18871970) ( Fig. 2 ) and his wife, Hildegard (or Hilda, as Hank preferred) ( Fig. 3 ), came to the Teton Range and Jackson Hole, Wyoming, for reasons that were intensely personalto raise a family and interpret the place they loved through Hanks landscape paintings and fine art photography. However, their achievements transcended their personal stories. Hank left a legacy of national park art that created a timeless vision of Grand Teton National Park and vicinity. The Crandall Picture Shop and Studio (hereafter referred to as the Crandall Studio) offered souvenirs to countless park visitors, thus providing them with a tangible remembrance of their vacation. Today, Hanks landscape paintings and his unique hand-painted photographs grace many fine homes in Jackson Hole and across the nation. Hank and Hildas old homestead property was returned to nature and will always be preserved at the heart of the park ( Fig. 1 ).

In 1922, Hank and Hilda Crandall packed all of their possessions into the back of their Ford Model T truck ( Fig. 4 ) and traveled from their home in Idaho to Jackson Hole. They navigated the primitive road across the Teton Pass and began an adventure to live out their dream. Hank wanted to interpret his ideal landscapethe Teton Range. Like so many Americans before them, the Crandall family had the fortitude and perseverance to make their dream come true. They made it through tough years of dry homesteading in Jackson Hole, building and running an art studio during the Great Depression and World War II, and weathering frontier controversies during turbulent times. The family operated the Crandall Studio for 34 years ( Fig. 5 ). They also operated a satellite studio in the shadow of Jackson Lake Dam in the old village of Moran. Today, old Moran exists in memories because the town site was given back to nature many years ago.

Fig. 1. The map shows the location of the Crandall homestead, now reclaimed by nature and representing preserved land at the heart of what is now Grand Teton National Park. Map by K. A. Barrick.