For Hunt, whose smile lights my way

AH

For Mom, Betsy, and Emily, with love

DB

Lyons Press is an imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2015 by Amber Hunt and David Batcher

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

eISBN 000-0-0000-0000-0 (eBook)

Hunt, Amber.

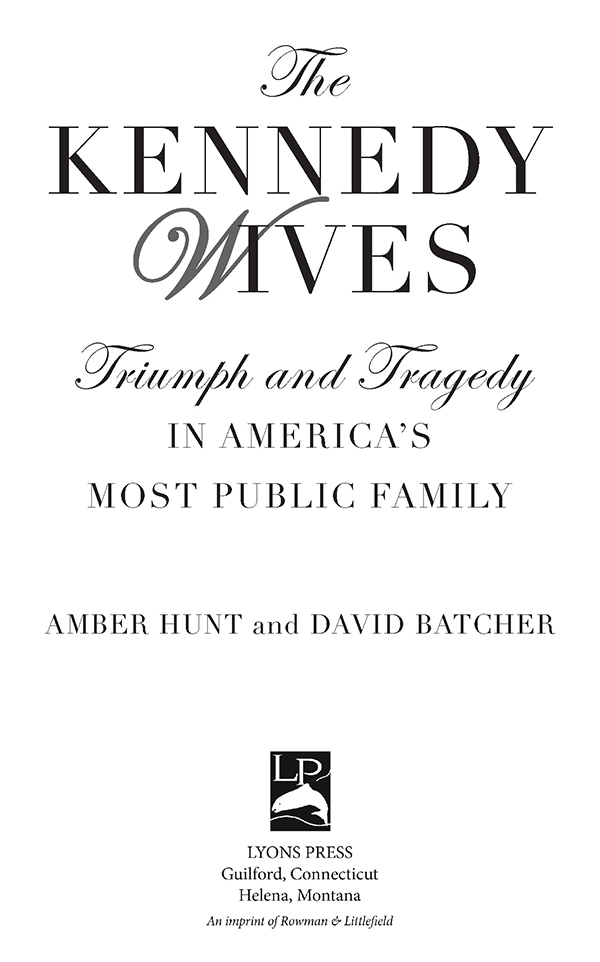

The Kennedy wives : triumph and tragedy in Americas most public family / Amber Hunt and David Batcher.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7627-9634-2 (alk. paper)

1. Kennedy, Rose Fitzgerald, 1890-1995. 2. Kennedy, Ethel, 1928- 3. Onassis, Jacqueline Kennedy, 1929-1994. 4. Kennedy, Joan Bennett. 5. Kennedy, Victoria Reggai, 1954- 6. Kennedy family. I. Batcher, David. II. Title.

E843.H86 2014

973.9220922dc23

2014034236

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Contents

From the Cradle

Josie Fitzgerald was afraid her baby might not last the week.

The summer of 1890 was brutally hot, and in the week following Rose Elizabeth Fitzgeralds birth, 284 Bostonians would diealmost half under the age of one. But Rose was as hearty a girl as a mother could hope for. She not only survived that first weekshe would live until 1995.

She would marry a man named Joe Kennedy, who would become one of the richest men in the nation. She would have nine children between 1915 and 1932, and shed raise them in homes in Boston, in New York, in Florida, and on Cape Cod. Traveling to Paris for shopping would become routine, just one of the many coping mechanisms shed use as she learned to look the other way; her husband cheated on her with hundreds of women. Shed see politically ambitious Joe named ambassador to the United Kingdom in 1938 and live in England on the brink of World War II.Shed pray the rosary and attend mass with great devotion. Shed return to the United States, the family name in tatters, after her husbands outspoken support of appeasement cost him the ambassadorship and seemingly any hope of a political future.

Shed write thank-you notes with scrupulous fidelity. Shed tragically lose two children to aviation disasters in the 1940s and see a third child institutionalized for life after a botched lobotomy. Shed hobnob with popes and drink tea with royalty. Shed see her remaining children marry, one by one, and watch as her three sons became a mid-twentieth-century political powerhouse. Shed see her Jack elected president of the United States, her Bobby named the countrys attorney general, her boy Teddy elected to the Senate. Shed advise world leaders and play hostess at the White House. Shed attend funerals for two sons, killed less than five years apart by assassins bullets, and a funeral for her husband, who died more than seven years after being immobilized by a stroke. Shed walk three miles a day and take bracing ocean swims. Shed stand by Teddy after a car accident off a bridge in Chappaquiddick left a young woman dead and his name splashed across the front of every tabloid in the world.

Shed write letters to her adult children about points of grammar. Shed watch one daughter marry a movie star and struggle with alcoholism. Shed watch another, inspired by the experience of having a special needs sister, found the Special Olympics. Shed watch her dozens of grandchildren struggle and achieve in politics, business, media, and philanthropy. Shed watch Teddy reach for the presidential nomination (and be relieved when he didnt get it). She would bow her head and accept Gods will. She would become a writer, a media personality, a symbol throughout the world of grace and fortitude in the face of tragedy, an example of service to country and humanity. She would see her name become an indelible part of American history.

In that stifling bedroom in North Boston, shy, pretty, sweet-natured Josie could not know it, but her daughter would see wonders.

Between Joe and Honey Fitz

As teenagers in the first decade of the twentieth century, Rose Fitzgerald and Joe Kennedy fell deeply in love. Roses father responded by sending her to a convent in Holland.

The protective father in question was career politician John Francis Honey Fitz Fitzgerald. Born in 1863 in Boston to Irish immigrants, Honey Fitz would come to cover the waterfront of Massachusetts politics; he served on the Boston Common Council, in the state senate, then for two terms in the US House of Representatives, then for two (noncontinuous) terms as the mayor of Boston. A short, powerfully built man with intense blue eyes, he was a born politician who loved to work a crowd. He crooned Sweet Adeline at nearly every campaign stop, was loud, brash, unrestrained on the stump, an indefatigable backslapper and handshaker. He married the lovely but much more retiring Josie Hannon in 1889 and Rose, the eldest of their six children, was born on July 22 of the following year. Josie was a deeply devout Catholic, and she inculcated strict adherence to the religion in the children, as would Rose a generation later with her nine children.

If daily mass and praying the rosary were habits Rose inherited from her mother, her father transmitted his love of campaigning. Shy Josie mostly abdicated her role as political wife in favor of raising her children. Mother had a limited capacity for the official social swirl, Rose would later write, and from an early age, the energetic, outgoing, articulate Rose served as her proxy. Ive been in the limelight since I was practically five years old, she was fond of saying. As a teenager, she was covered by the local newspapers as she joined her father on many public appearances.

When not appearing at campaign stops with her flamboyant father, she was attending a series of Catholic schools, where the nuns further instilled in her the importance of personal, daily devotion to the faith.

Roses upbringing was Victorian, an era and ethos that from our vantage seem archaic, restrictive, and conservative. Women actualized themselves, according to Victorian mores, in motherhood. The one progressive impulse in the Victorian era was the new insistence that girls should be well educatedthat they be so in order to better raise educated sons was taken for granted. It seems that Rose never seriously questioned any of this. As motherhood is the greatest and most natural God-given gift for women for posterity, she would write in the 1960s, it would seem that the birth and rearing of children in the way which to us seems most ideal, would be the most satisfying and the most rewarding career for a woman. In motherhood, she believed, was real power: the power to mold a child. Her words will influence him, not for a day or a month or a year, but for time and eternity and perhaps for future generations.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.