For Alex and Sam

Everyone wants to fly too close to the sun

John Curry

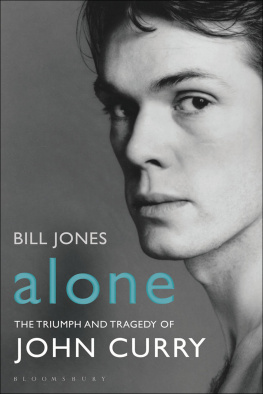

On a cold winters evening in February 1976, 20 million Britons turned on their television sets to watch the ice skating. It didnt matter that most of them, myself included, knew nothing about the sport. All of us were in the grip of something mystical, something transcendental, something far beyond the delirium of a Briton in pole position for Olympic glory. On paper, it made no sense. With its salchows and spins, its loops and lutzes, figure skating spoke an alien language. But this man; this beautiful man. He made absolute sense, and all of us from Bridlington to Bournemouth were glued. John Curry. That was his name. At times, he had seemed like an alien, too.

He had won, of course. In 50 glorious days he had won everything. The European, the Olympic, and World titles were all his. Even to mere mortals, able only to shuffle in their shoes, it was clear that we had all witnessed some kind of sporting epiphany. Curry had not been merely on the ice. He had been of the ice, his energy seemingly drawn from deep within the earth. Where muscled men normally preened like mating cocks, Curry had flown and swooped, his back peerlessly arched, the pencil-thin blade of his skates slicing a soundless masterpiece into the ice.

In that brief moment, through the restrained mastery of Currys triumph, sport had, for a moment, stood high above itself. All of us, in our ignorance, had felt the plates shift. Out of the intricate absurdities of rules and competition and Cold War politics, this permed Adonis had created something life-affirming. Driven by John Currys feet, sport had transfigured itself into art. Masculinity, for its own sake, had been trounced by beauty. And therein lay another reason why so many millions had watched, and why Curry intrigued every one of them.

For decades, sportsmen had worn their testosterone like a badge of honour. Currys skating was mesmeric and sensual erotic, too but stereotypically masculine? No. Women adored him. And men, or lots of them, bereft of anything better, resorted to the lexicon of the barracks. Curry skated like a gay like a woman they whispered, and in the hours which followed his Olympic gold, his secret had bled out; inadvisably shared with a reporter who had promptly passed on his scoop to the world.

In mid-1970s Britain, few people openly admitted to being gay and celebrity disclosure was virtually unknown. After the Olympics, Curry would have been famous anyway. In the light of his coming out, however, the skaters overnight fame acquired a sinister edge. Suddenly, everyone wanted a piece of him. Chat shows, newspapers, magazines, advertisers, impresarios and even would-be wives beat a path to his door. Parkinson wanted him. The Queen wanted him. The BBC Sports Personality of the Year wanted him. In 1976, few faces were better known and, to all who wooed him, Curry was charming, polite, well-spoken and happy to flesh out the bones of his life story so far.

Born into a prosperous self-made West Midlands family, he had wanted to be a dancer from the age of seven. Unable to secure his fathers blessing for ballet lessons, hed turned to skating to find release for his musically expressive urges. To reach the pinnacle of figure skating hed fought the sports resistance to his style for 20 years. Now he was there, and his intention was to create a theatre of skating; a glorious new art form that would conquer the world. At which point for most of the millions who had watched him weeping on a podium in Innsbruck Currys story abruptly ends. Ask around today, and no one seems sure what happened to him. Is he alive? Is he dead? Wasnt he the fairy who won the skating?

The reality as I have spent over two years finding out is one of the most moving lives of any post-war British public figure. From his fathers suicide to Currys AIDS-related death at the age of 44 in 1994 it is a story parenthesised by tragedy but filled out with courage and achievement at the highest level. True to his promise, Curry played at the Royal Albert Hall, the New York Metropolitan Opera House, the London Palladium and the John F. Kennedy Center in Washington, DC. Wherever he performed, his bold, new work was fted. In Manhattan, where he lived for many years, he could do no wrong. In Britain, where homophobia had blighted his early years, he was cruelly forgotten.

For a biographer, Currys performing life was relatively easy to unravel. Curry the man, on the other hand, was (and to some extent remains) a much harder proposition. How do you write a book about a black hole? pondered one of his friends. It was a good question. From an early age, the skater had been predisposed towards secrecy. Little he saw in his life gave him reason to amend that stance. As a teenager, he knew that his homosexuality might have led him to prison. As an AIDS victim, he was consumed by fear, shame and self-loathing. Along the 25-year journey between those two points, Curry rarely shifted from obsessively private.

Out on the ice, Curry was never short of miraculous. Away from it, he was possessed by such morbid darkness it robbed him of joy. Despite a string of lovers he usually failed to establish lasting relationships and lived mostly alone. His sexual tastes were violent, and his moods could swerve dangerously from near-suicidal to diva-like bullying. Nothing he did seemed to please him. No pleasure ever seemed to last. He mercilessly sacked coaches, producers, managers and skaters with selfish abandon. And yet he could bring tears to the eyes of anyone who watched him skate. To say he was conflicted is an understatement. To describe him as a black hole is not far short of the mark.

Thankfully, a number of small miracles have helped me throw light into that darkness. From two sources, around 200 of Currys letters have informed this long process; some to his first lover, Heinz Wirz, the rest to the remarkable woman in New York who adopted him. To read them is to hear Currys true voice. At times, cruel. At times, wildly funny and sexually explicit. At times, bursting with expectation. In many of them, no details are spared especially to Wirz. In almost all of them, you can hear the pleading voice of a lonely child, wrestling with the torment of his genius and hungry for approval. In one of the letters there sits a forlorn lock of his hair. Even the countless addresses are revealing. Peripatetic, rootless, constantly on the move, Curry never stayed anywhere long and the inside pages of his three battered passports are a blizzard of red ink.

Alongside the correspondence I have also drawn on conversations with around a hundred people who knew him well or thought they did. Skaters, musicians, lovers, actors, ice engineers, directors, producers, coaches, childhood friends, adult friends and close family. Each was familiar with one side of him. Very few got the whole picture. And many of his male friends are already dead.

Currys story is not just a life. From his first clandestine gropings, through the release of liberation to the curse of AIDS, his 44 years trace a heartbreaking path that was followed by an entire generation of men. More Americans died of AIDS, it is said, than fell in Vietnam. In the blighted company of John Curry that nightmare passage takes human flesh. In New York, one by one, his friends and ex-lovers were consumed. As solitude crowded in, he fled home where, in the final years of his life, he allowed the world to see what disease had done to his magnificent body.

Next page