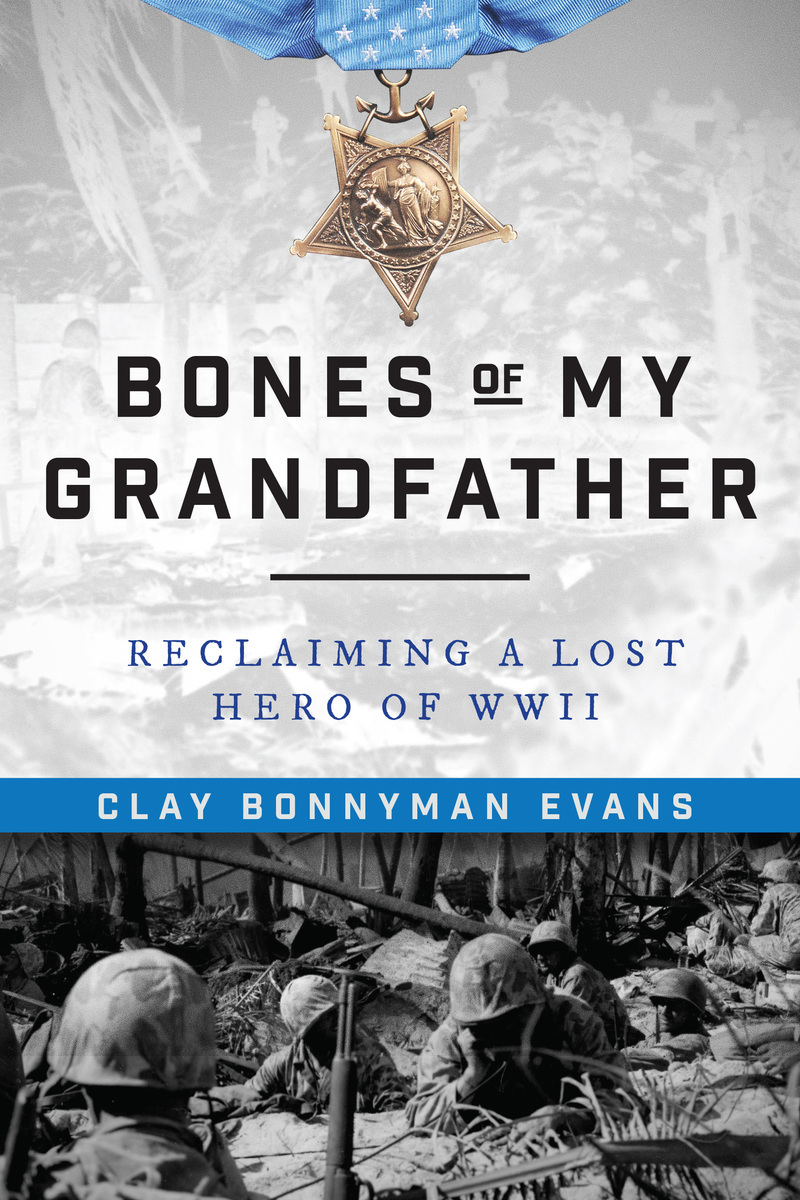

Copyright 2018 by Clay Bonnyman Evans

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com .

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Rain Saukas

Cover photos courtesy of Clay Bonnyman Evans

ISBN: 978-1-5107-3061-8

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-3062-5

Printed in the United States of America

Ive always wished to be laid when I died

In a little churchyard on the green hillside.

By my fathers grave, there let me be,

O bury me not on the lone prairie.

THE COWBOYS LAMENT, TRADITIONAL

Death is only a state in which the others are left.

Its reality explodes only in the living.

WILLIAM FAULKNER

Show me a hero and I will write you a tragedy.

F. SCOTT FITZGERALD

To my grandfathers three blondes, who paid a bitter price:

Frances Bonnyman Evans

Alexandra Bonnyman Prejean

Josephine Tina Bonnyman

and

To Mark Noah, the right man at the right timejust like Sandy

CONTENTS

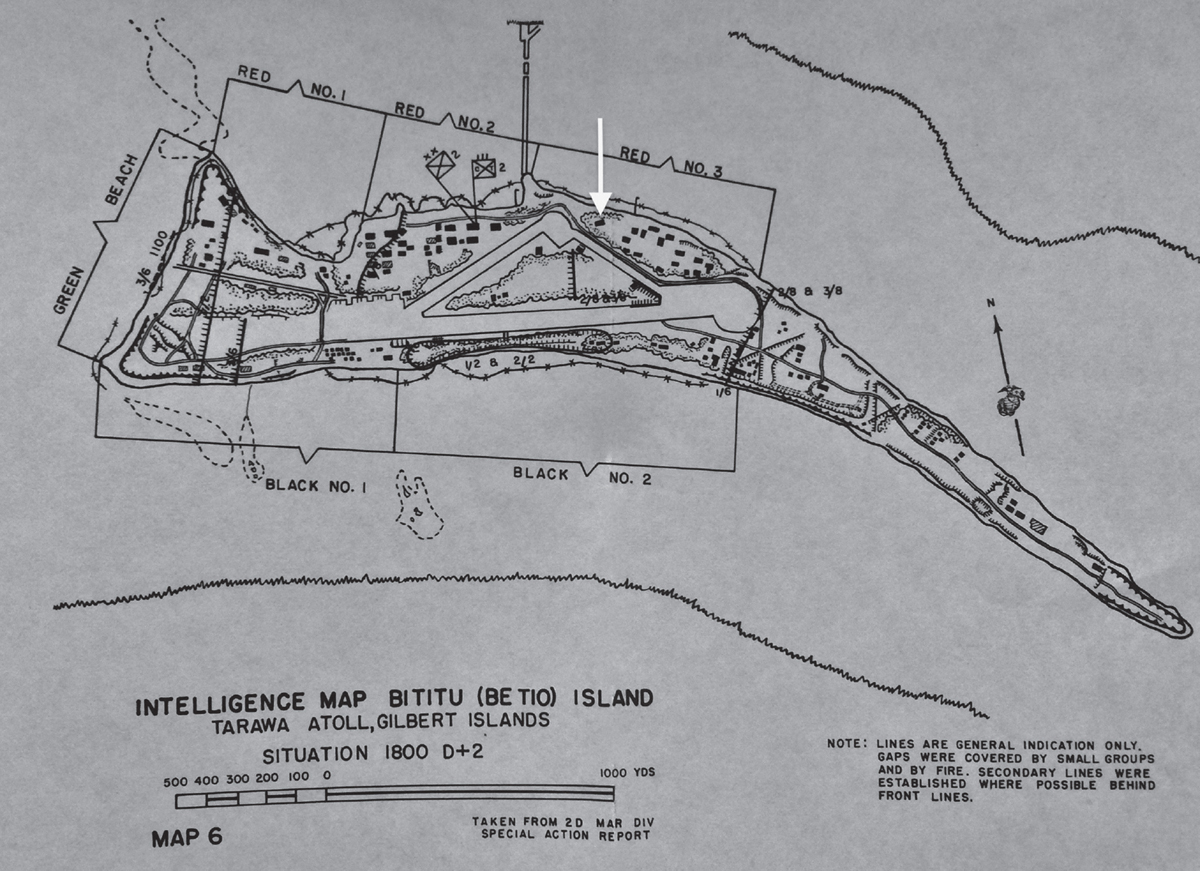

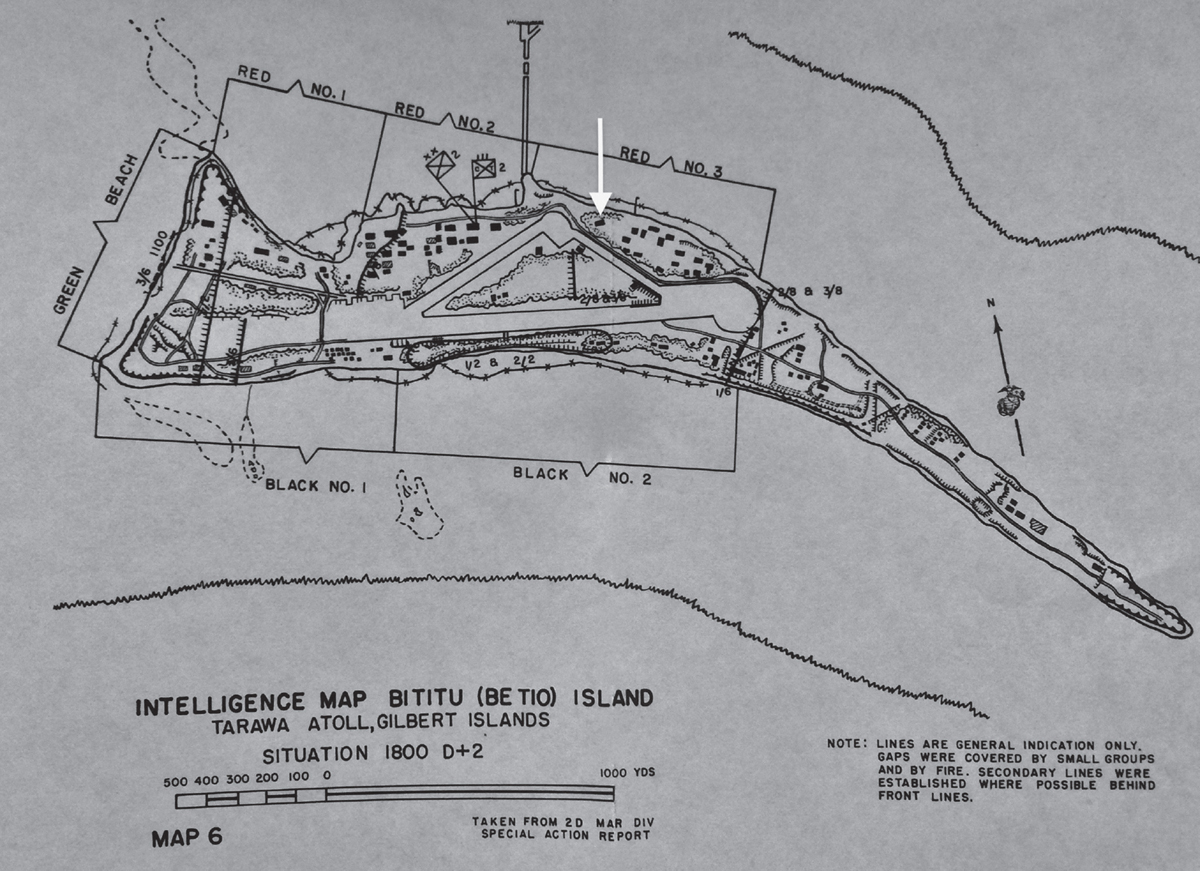

Situation map of Betio island, Tarawa Atoll, Gilbert Islands at 6 p.m. November 22, 1943. The arrow indicates the location of the bunker where Sandy Bonnyman was killed earlier that day. US Marine Corps Historical Division.

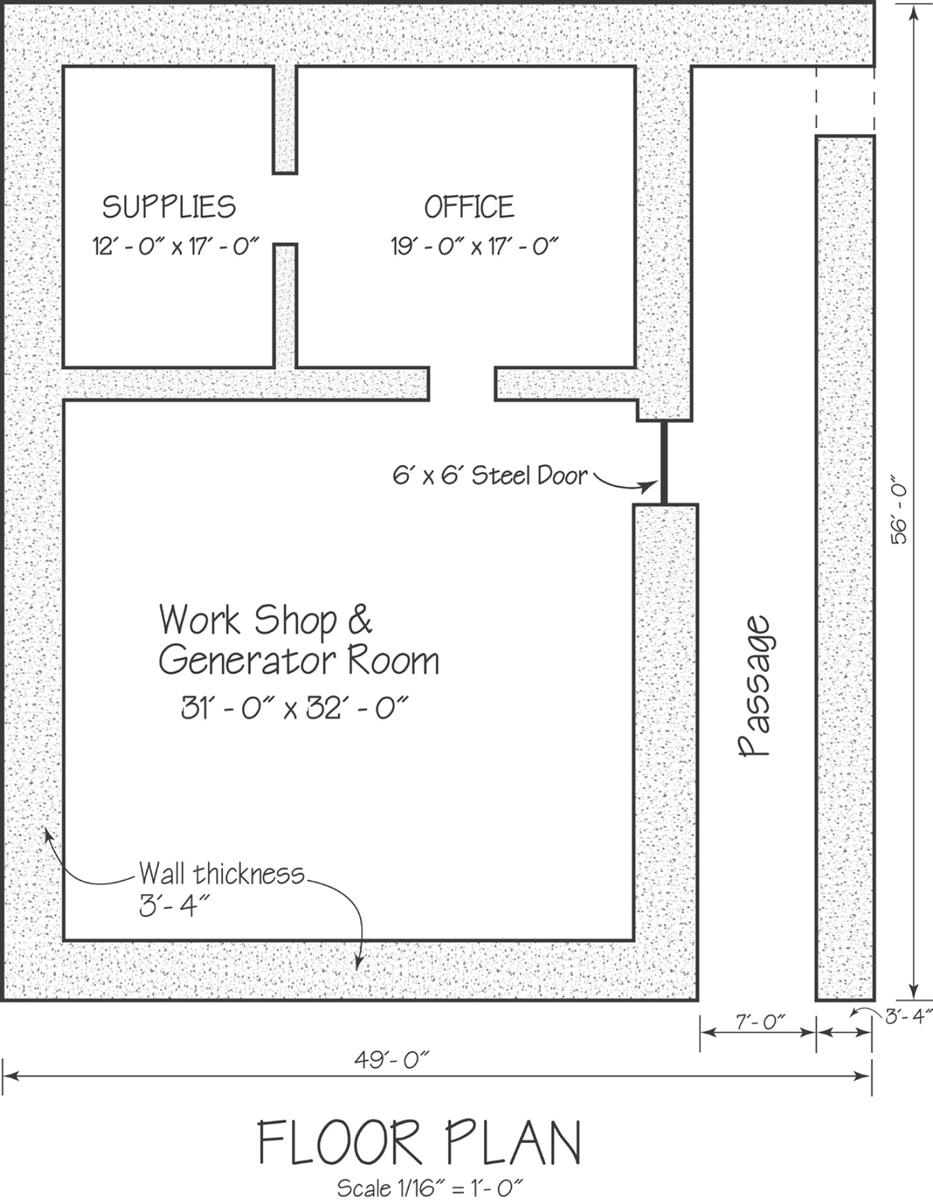

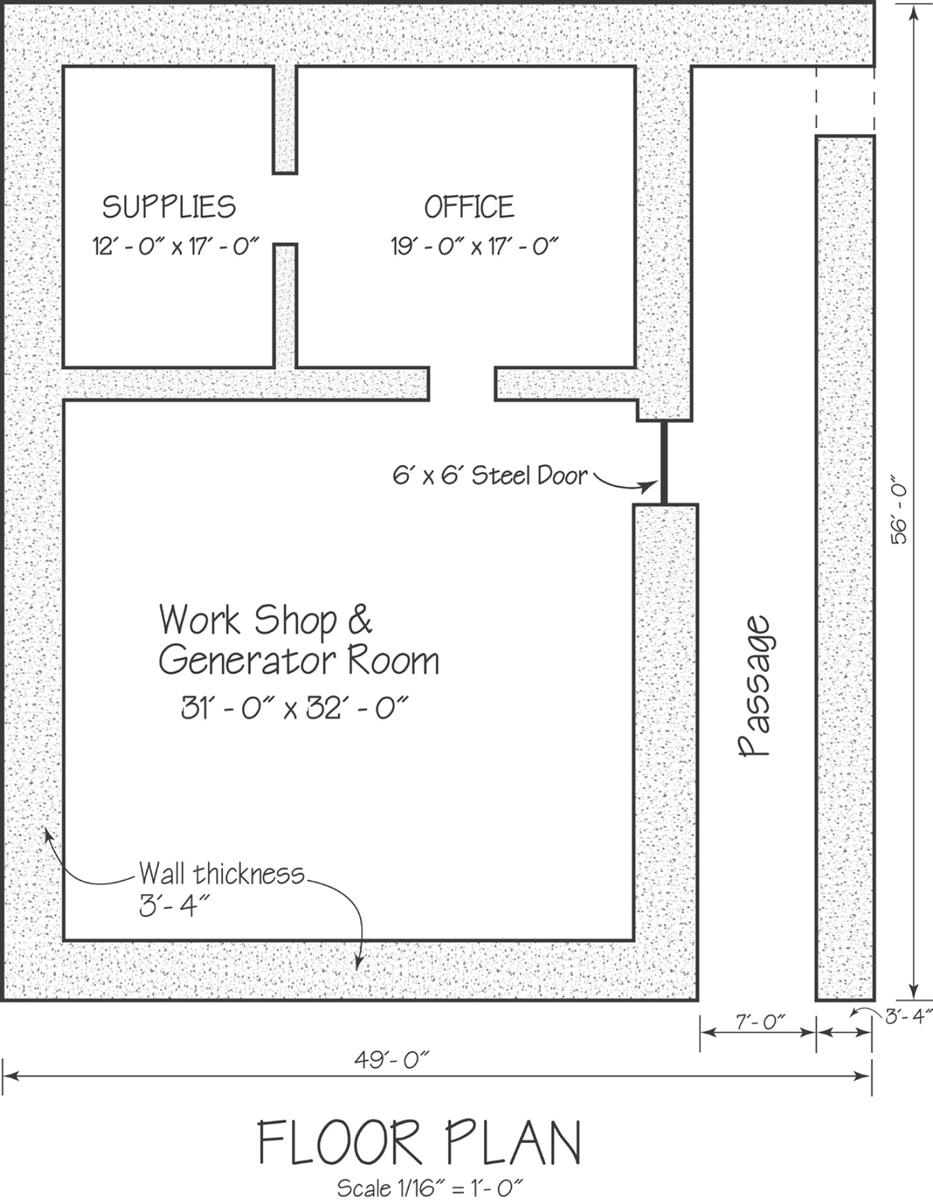

Schematic of Bonnymans Bunker, drawn December 12, 1943, following the battle. Julie Kunkel rendering; original, Marine Corps Combat Art Collection.

PROLOGUE

JANUARY 1944

She was nine years old when the whispering began in late December 1943.

Golden-haired, athletic, wary, and more than a little impetuous, Frances Bonnyman had attended five schools in the past year. She had liked Mrs. Turleys one-room private academy in Santa Fe, where her family had been living since her father began operating a copper mine in 1938. She loved the exotic mlange of culturesSpanish, Pueblo, Angloin the high-desert town at the foot of the pine-dark, sere Sangre de Cristo Mountains, where she attended Indian dances and picked up Spanish from neighborhood playmates.

She didnt see much of her mother Josephine, or Jo, but that was all right by her. She and her younger sister Tina were well cared for by the cook, Casamira, Sister Michelle, a nun hired by their grandmother to instruct them in the Catholic faith, and sometimes, the parents of friends and neighbors. Baby Alexandra, called Alix, was born in 1940 and had her own nurse, Miss Rosa Dee.

Fran didnt see a lot of her father, either. Tall, handsome Alexander Bonnyman, Jr.known to all as Sandyspent five or six days a week running the mine near Santa Rosa, more than a hundred miles of bad road distant, on the spare plains of eastern New Mexico. But he doted on his oldest daughter when he came home on weekends, holding her hand as they walked in to Sunday Mass at the soaring, ornate Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi. Afterwards, they always went to the Capitol Pharmacy soda fountain for a chocolate shake or soda.

Fran would never forget one Sunday in particular, as she watched her father pace the floor with intense agitation, the radio buzzing and crackling in the background with the frightening news that the Japanese Empire had attacked the United States at faraway Pearl Harbor. Seven months later, her father, thirty-two, would board a train to California as a private in the United States Marine Corps Reserve.

Fran missed him and wrote him often on cream-colored stationery with the image of a small, smiling marine in dress blues on top: When are you coming home? I wish I could see you now! Sandy wrote to his big girl just as often, urging her to keep up her straight As, go to Communion every Sunday and confession at least every two weeks, be nice to her sisters, and help Mommie and Dee. He sent her dollar bills for doing chin-ups and improving her swimming skills.

The summer of 1943, Jo left the girls in Knoxville to stay with their Granny and Grandfather Bonnyman. But at summers end, instead of taking them back to New Mexico, she enrolled Fran in school in Tennessee, left frail, sickly Tina in Knoxville, and moved with baby Alix and Dee to Mooneys Cottages, a cluster of new, Key West-style bungalows on the beach in Fort Lauderdale. Jo returned in November to take Fran to Florida, leaving Tina with her grandparents.

As Christmas approached, Fran was excited to hear hopeful chatter among the adults that her father might come home to visit. Her cousin Sandy, just six months older, had received a V-Mail in mid-December, postmarked November 16 and featuring a cartoon crocodile in a marine helmet proclaiming, To you in the States from us in the South Pacific, Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year, and the hand-written message, To Sandy with wishes for the Best of Christmases from Uncle Sandy. But Fran hadnt had a letter in many weeks.

What Fran, Jo, and her grandparents didnt know was that Sandy had sailed from Wellington, New Zealand on November 1, arriving a week later at Mele Bay on the island of Efate in the Solomon Islands, where the Second Marine Division rehearsed amphibious landings in preparation for an assault on a remote coral atoll nobody had ever heard of. But by the end of the month the name would be splashed across front pages as the site of the bloodiest battle in Marine Corps history: Tarawa.

The banner headline in the New York Times on November 25 read, RUINED BERLIN AFIRE AFTER 2D BOMBING; U.S. PLANES SMASH AT TOULON AND SOFIA; 4 JAPANESE DESTROYERS SUNK IN BATTLE. Below the fold, a three-paragraph notice reported that marine assault battalions had conquered the west end of Betio Island, on Tarawa atoll, under the headline, WE WIN GILBERTS IN 76-HOUR BATTLE.

Correspondent George F. Horne, whom the Times had sent to Honolulu after government news blackouts had rendered his previous beat covering shipping news on the New York waterfront obsolete, was unimpressed. The victory, he wrote, was not of major nor decisive character, and his dispatch dripped with drollery: Bemused mathematicians were uncertain today as to the time length of the Gilbert Island occupation. First it was 100 hours, but official rewriting now makes it 76 hours, although lesser statisticians wandering hereabouts with pencil and paper figure slightly more.

The remote Gilbert Islands straddled the Pacific equator and had been under British control until the Japanese had arrived two days after Pearl Harbor. The place had hardly been mentioned in US papers until then, though the Times did run a small story in September reporting that American forces had conducted heavy bombing operations on Tarawa. And to many Americans, the foe in the Pacific, those funny little yellow men with buckteeth and thick, round spectacles, were a joke compared to the mighty mechanized armies of Nazi Germany. The press had convinced much of the public that the Japanese would be a pushover.

Next page