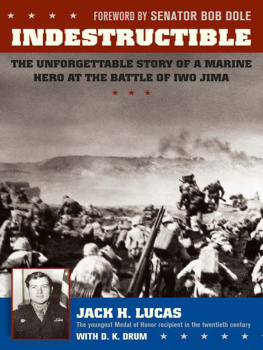

Copyright 2006 by Jack H. Lucas and D. K. Drum

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America.

Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 11 Cambridge Center, Cambridge, MA 02142, or call (800) 255-1514 or (617) 252-5298, or email

Neither the United States Marine Corps nor any other compononent of the Department of Defense has approved, endorsed, or authorized this product.

Foreword

by Senator Bob Dole

I t is often said that the true heroes of war are the ones who dont come back. In the terrible Battle of Iwo Jima, America lost 6,821 such heroes. But for the hand of God, Jack Lucas would have been one of them. During some of the most intense fighting on that sulfur island, on D day plus one, two grenades rolled into Lucass trench. Without hesitation, the seventeen-year-old threw himself on one and pulled the second underneath his body, absorbing a deadly blast with his own flesh and bone. Though he saved the three Marines who were with him, he did much more than that. By that act Jack Lucas exemplified with his own blood and grit the spirit of sacrifice that won the war in the Pacific. All Americans should know his story; our foes should contemplate it.

Jacks life was not unlike my own. We both grew up during the Depression as middle-class kids in a small town, though my experience was spent in Kansas and his in North Carolina. When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor we both knew it was our destiny to answer our nations call. I was a college freshman whose biggest concerns were planning the next fraternity party and finding a date for Saturday night. Jack, on the other hand, was still being told what time to go to bed, and his biggest plan was graduating eighth grade.

Though I knew it was inevitable I would serve, I pondered the time of my enlistment. Jack was ready to join the Marines while the bombs were still falling on Pearl Harbor. It took him almost nine months to wrangle his way past the bureaucracy that should have kept him home, entering service four months before I signed up.

While I was fighting Nazis in Italy, Jack was fighting the Japanese in the Pacific. Both of us witnessed a staggering loss of young American lives. Our own lives were forever changed by grievous personal injuries suffered in combat.

Jack and I know the horror of feeling life draining from our bodies as we lay on the field of battle, trapped in a dull haze and comforted only by morphine. We are given only one body, and when it is broken in service to others, we have given a most precious gift. Jack and I would learn to write left-handed, athletics would forever be out of the question, and our internal injuries would require a lifetime of attention. We were fortunate; at least we would have a lifetime.

Jack and I have looked over the edge into the darkness that is death and survived to tell of the ghastliness that is war. War is not glamorous. It is ugly business and no one escapes its effects. It cant be explained adequately to someone who has never been there.

Men are never closer than when they are under fire together. In World War II, we were all brothers on the battlefield. As survivors, we are left to remember those who paid the ultimate price. They too are our brothers, a relationship born in battle, baptized in blood, and immortal in spirit. We honor their memory.

From all walks of life they came, from the mountains, prairies, cities, and farms, they joined to serve. Death gave no heed to the privilege of their birth. They laid down their lives for the cause of freedom and for their buddies in the foxhole with them.

I have always felt that what gets people through a physical or emotional crisis is having a foundation of faith in God, believing that life matters and that theres a bigger plan in play than what we can see with our human eyes. In my own memoirs I wrote

[We] need one another to defend one another, to depend on one another. They say every soldier on the front saves every other soldiers life and has his life saved by another soldier nearby.

Thats the fighting mans job. Jack did his job well and, like so many that have served their country, I am proud to call him my brother.

Prologue

And when he gets to Heaven to St. Peter he will tell: One more Marine reporting, Sir. I've served my time in Hell.

Sergeant James A. Donahue, 1st Marine

Division

T hough I was just thirteen when I decided to march on Japan, ride the wave of American retribution, and make the Japanese pay for the attack on Pearl Harbor, I had already passed from boy to man. I thought I knew it all. Though I had yet to see friends evaporate before my eyes, or an enemy bleed out and die by my own hand, I had loved and now I had hated and I considered myself more than ready to go to war.

That I would find both the need and the strength to pull a live hand grenade to my gut while a second grenade lay beneath me, ready to detonate, would have astonished me even in my moments of greatest bravado. I went to war with vengeance in my heart. I went to war to kill. Such is the irony of fate that I will be remembered for saving the lives of three men I barely knew.

My journey into manhood began one bleak October afternoon when my beloved father drew his final breath, having lost his long battle with cancer. I was eleven years old. Afterward, I pushed away any man the lovely widow, Margaret Lucas, attempted to bring into our lives. I did not need a man; I was one. I was a tough kid who loved to fight. I was rebellious by nature and had a hairtrigger temper. Troubled in general: that was the young Jack Lucas.

As my inner turmoil heated up so did world events, and with the reprehensible bombing of Pearl Harbor, we both boiled over. I lived by my wits and often made up my own rules, leaving a trail of broken jaws and busted lips as I went along. So, it was not much of a stretch on my part when I found a way to join the United States Marine Corps, though I was only fourteen at the time. I went AWOL to catch a train headed in the direction of the war. Then I stowed away on a ship to reach one of the Pacifics worst battlefields. I figured, if I figured anything at all, that if I was shrewd enough to impose my will on the United States Marine Corps, the Japs would give me little trouble.