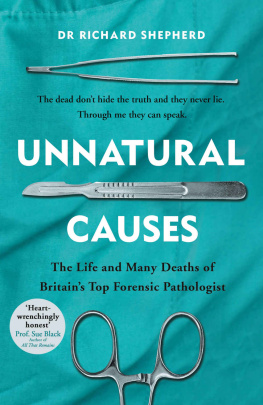

Dr Richard Shepherd

UNNATURAL CAUSES

MICHAEL JOSEPH

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2018

Copyright Richard Shepherd, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Designed by Andrew Smith

Cover image Alamy

ISBN: 978-1-405-92355-2

Authors Note

It was difficult for me to take the decision to change names and identifying details in this book because Ive spent a working life striving for accuracy. However, Ive also spent a working life trying to alleviate the suffering of the bereaved and it would help no one to recognize a relative in these pages and revisit their darkest days here. So only the names of those who are so famous they are impossible to disguise are given. In all other cases I have changed details to preserve confidentiality while maintaining relevant facts.

Tis not enough, Taste, Judgement, Learning, join;

In all you speak, let Truth and Candour shine:

That not alone what to your Sense is due,

All may allow; but seek your Friendship too.

Be silent always when you doubt your Sense;

And speak, tho sure, with seeming Diffidence:

Some positive, persisting Fops we know,

Who, if once wrong, will needs be always so;

But you, with Pleasure own your Errors past,

And make each Day a Critick on the last.

Tis not enough your Counsel still be true;

Blunt Truths more Mischief than nice Falsehoods do;

Men must be taught as if you taught them not;

And Things unknown proposd as Things forgot.

Without Good Breeding, Truth is disapprovd;

That only makes Superior Sense belovd.

Be Niggards of Advice on no Pretence;

For the worst Avarice is that of Sense:

With mean Complacence neer betray your Trust,

Nor be so Civil as to prove Unjust.

Fear not the Anger of the Wise to raise;

Those best can bear Reproof, who merit Praise.

Alexander Pope, An Essay on Criticism

1

Clouds ahead. Some were snowy mountains looming over me. Others lay across the sky like long, sleeping giants. I moved the controls so gently that when the plane tilted down and to the left it seemed to respond not to command but by instinct. Then, ahead of me, the horizon straightened. It is a strange friend: always there, glimmering between sky and land, unapproachable, untouchable.

Beneath were the North Downs, their gentle curves bearing an odd similarity to the rise and fall of the human body. Now they were sliced cleanly through by the motorway. Cars chased each other along its deep cut. They gleamed like tiny fish. Then the M4 was gone and the earth was falling away towards water, a river knitted with a complexity of tributaries.

And here a town, its centre robust, red-hearted, radiating roads lined by paler, more modern buildings.

I swallowed.

The town was disintegrating.

I blinked.

An earthquake?

The towns colours waved. Its buildings were pebbles on a riverbed, viewed through the distorting lens of flowing water.

Extraordinary air currents?

No. Because the town waved in time with something inside me, something like nausea. But more ominous.

I blinked harder and my hand tightened on the planes controls as if I could correct this feeling by correcting altitude or direction. But it came from deep inside me, forcing its way up through my body with a physical power that left me breathless.

I am a practical, sensible man. I looked for practical, sensible explanations. What had I eaten for breakfast? Toast? Harmless enough and offering no explanation for the sudden intensity of this sickness. And if it wasnt exactly nausea, then what? Its chief component was an inexplicable sense of unhappiness, and yes, dread. A sense that something terrible was about to happen. Even an urge to make it happen.

A ludicrous, irrational thought crossed my mind. What if I got out of the aeroplane?

I struggled with myself to remain seated, to keep breathing, to control the plane, to blink. To be normal again.

And then I glanced at the GPS. And read: Hungerford.

Red, older houses at the centre. Hungerford. On its peripheries, grey streets and playing fields. Hungerford.

And then it was gone, replaced by Savernake Forest, a vast green cushion of vegetation. Gradually the great forest brought me relief, as if I were a foot-traveller enjoying its leafy shade. If my heart rate was still raised the cause was retrospective horror. What had happened to me back there?

I am in my sixties. As a forensic pathologist, I have performed more than 20,000 post-mortems. But this recent experience was the first time in my entire career that I suspected my job, which has introduced me to the human body in death after illness, decomposition, crime, massacre, explosion, burial and pulverizing mass disasters, might have emotional repercussions.

Lets not call it a panic attack. But it shocked me into asking myself questions. Should I see a psychologist? Or even a psychiatrist? And, more worryingly, did I want to stop doing this work?

2

The Hungerford massacre, as it became known, was my first major case as a forensic pathologist and came absurdly soon after I began my career. I was young and keen and it had taken many years to qualify. Years of highly specialized training, far beyond routine anatomical and pathological study. I must admit that so much time spent staring at minute cellular differences on microscope slides nearly bored me into giving it up. On many occasions I had to reinspire myself by sneaking into the office of my forensic mentor, Dr Rufus Crompton. He let me read through his files and look at the booklets of photographs from his cases and sometimes Id sit there, engrossed, long into the evening. And by the time I left I could remind myself why I was doing all this.

At last I qualified. I was rapidly installed at Guys Hospital, in the Department of Forensic Medicine, under the wing of the man who was then the UKs best-known pathologist, Dr Iain West.

In those days, the late 1980s, pathologists were expected to join senior police officers as hard-drinking, tough-talking, alpha males. Those who carry out necessary work that repulses others often feel entitled to walk with a swagger in their step and Iain had that swagger. He was a charismatic man, an excellent pathologist and a bull in the witness box who was not scared to lock horns with counsel. He knew how to drink, charm women and hold a public bar spellbound with a good story. Although sometimes rather shy, I had almost convinced myself I was socially competent until I found myself playing the gawky younger brother to Iain. His light shone in pubs across London and I stood with an admiring audience in his shadow, seldom daring to risk adding a quip of my own. Or perhaps that was just because I couldnt think of a good one, anyway not until at least an hour later.