Table of Contents

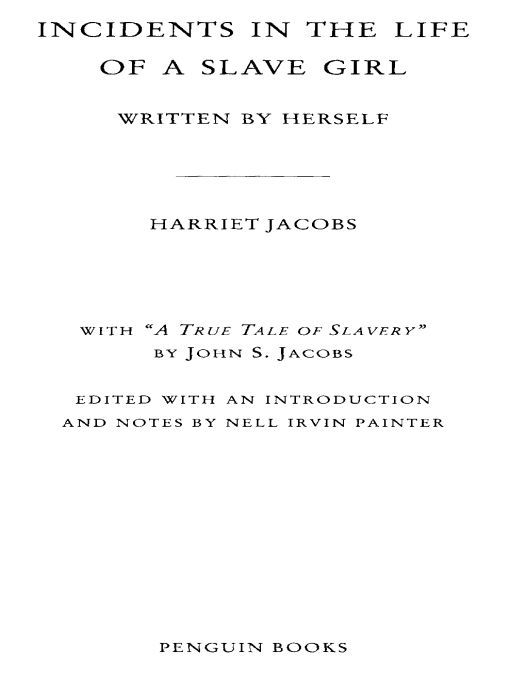

INCIDENTS IN THE LIFE OF A SLAVE GIRL

Harriet Ann Brent Jacobs was born in about 1813 in Edenton, North Carolina. Her brother, John S. Jacobs, was born two years later. Their parents, Delilah and Elijah Jacobs, were enslaved, but they lived together as a family with Delilahs mother until Delilahs death. Harriet, then six, went to live with her owner, Margaret Horniblow, who taught her to read and sew. When Margaret Horniblow died in 1825, Harriet became the slave to Horniblows three-year-old niece, the daughter of Dr. James Norcom, a prominent citizen, who tried to force the teenaged Harriet into a sexual relationship with him. In an effort to fend off his advances, she began a relationship with another white man, Samuel Tredwell Sawyer, and bore him two children, whom Norcom planned to send to a plantation with a reputation for treating its slaves especially brutally. To divert him, Harriet ran away, eventually hiding in a crawl space in her grandmothers house where she remained for almost seven years before escaping to the North in 1842. She lived and worked in New York City and Boston until her freedom was purchased in 1852. In the meantime, Sawyer managed to purchase his and Harriets two children as well as her brother John, who went on to work for the abolitionist cause. Harriet Jacobs wrote Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl between 1853 and 1858, finally publishing it in 1861 under the pseudonym Linda Brent. John S. Jacobs died in 1875. Harriet Jacobs died in 1897.

Nell Irvin Painter is Edwards Professor of American History at Princeton University, where she currently heads the Program in African-American Studies. She is the author of several books, including Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol, and editor of the Penguin Classics edition of the Narrative of Sojourner Truth.

INTRODUCTION

HARRIET JACOBSS LINDA: Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, seven years concealed in Slavery, Written by Herself (1861), the best-known nineteenth-century African-American womans autobiography, makes a marked contribution to American history and letters by having been written, as Jacobs stressed, by herself.

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl makes three important points convincingly: It shows, first, the myriad traumas owners and their agents inflicted upon slaves. Bloody whippings and rapes constituted ground zero of the enslaved condition, but in addition, slaves were subject to a whole series of soul-murdering psychological violations: destruction of families, abandonment of children, sexual harassment, verbal abuse, humiliation, contempt. Jacobs details the physical violence so common in her Southern world, but she especially stresses the assault on slaves psyches. Second, she denounces the figure of the happy darky. As a slave and later as an abolitionist, she was frequently confronted with this favorite American myth, which she knew to be false. In answer to this proslavery argument, she enumerates the miseries of the enslaved; in chapter 13 she shows precisely how Northerners were gulled into believing black people liked being enslaved within the fabric of an evil system, working the system allowed them only a modicum of self-determination. Because they literally belonged to other people, slaves lacked the power to protect their morals, their bodily integrity, or their children.

In sum, Jacobs delineates a system in which the enslaved and their enslavers (aided and abetted by Northern sympathizers) were totally at odds or, as she says, at war. As she sees it, there could be no identity of interest between the two parties to the peculiar institution, even though lives and bloodlines frequently intersected. The frequent occurrence of similar namesfor example, Margaret Horniblow (Harriets first owner) and Molly Horniblow (Harriets grandmother)may confuse the reader but attest to these very intersections.

Harriet Ann Brent Jacobs was born in about 1813 in Edenton, North Carolina. Jacobs, were enslaved, but they lived together as a family with Delilahs mother, Molly Horniblow. Horniblow, the daughter of a South Carolina planter who emancipated her during the Revolutionary War and sent her to freedom outside the United States, had been captured, returned to American territory, and fraudulently reenslaved after her fathers death. The head chef at the Horniblow Inn in Edenton, Molly Horniblow managed to earn and save money as a caterer even while enslaved. Her industry and clientele made her well known, well respected, and well connected in Edenton, and even before being freed again at the age of fifty, she had accrued as much standing as possible by one who was neither white nor free.

As a slave, Horniblow could not marry, yet her daughter Delilah and her husband Elijah lived with Molly as a married couple: Delilah even wore a wedding ring, which she left to her daughter Harriet. Horniblows effective marital status, on the other hand, remains a mystery, as does the never mentioned existence or identity of her own childrens father. These silencesin the historical record, in Harriet Jacobss Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, and in John S. Jacobss A True Tale of Slaveryspeak volumes, given Horniblows seemingly hypocritical attachment to the feminine ideal of chastity. Her insistence on premarital sexual purity, a condition which often eluded even free poor and working-class white women, would wreak havoc in her enslaved granddaughters emotional life.

Neither Harriet nor John recalled much about their mother, who died when Harriet was about six and John about four years old, although Harriet later praised Delilah as noble and womanly in nature.

By dint of their skills, values, connections, and ancestry, the entire Jacobs family had much in common with Edentons elite. However, their African descent, legal status as slaves, and extreme vulnerability placed them firmly on the wrong side of a towering color bar. Molly Horniblow and her grandchildren experienced the ambiguities of their allegiances differently. The grandchildren admired, but could not share, her heartfelt Christian piety. The grandmother counted on the existence of conscience in the slaveowning class, another faith beyond her grandchildrens reach. She sought decent treatment through personal entreaty; they both followed the route of permanent escape. Horniblows son Joseph shared her grandchildrens hatred of slavery; he ran away twice, the second time intending to leave the United States for good. Punning on the common term for whipping, he told his brother that he meant to get beyond the reach of the stars and stripes of America.

The Jacobses lived on the left bank of the Chowan River where it empties into Albemarle Sound. Connected through internal waterways with Hampton Roads, Virginia, and the Chesapeake Bay during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Edenton served as an administrative center for its own Chowan and surrounding counties and as northeastern North Carolinas main port. In 1820, the population numbered 1261, of whom 634 were white, 499 enslaved, and 67 free black. During Harriets and Johns youth, Edenton was still vibrant enough as a trading center that the towns leading families would station members in the New York area. The Tredwells and Blounts in Brooklyn, New York, who made the Jacobses later residence there unsafe, belonged to Edentons merchant families. During the mid-nineteenth century, Edenton lost importance as the Albemarle Sound silted up and North Carolinas economy shifted away from the heavily slaveholding and agricultural East Coast toward the diversified farming and industry located in the Piedmont farther inland.