Table of Contents

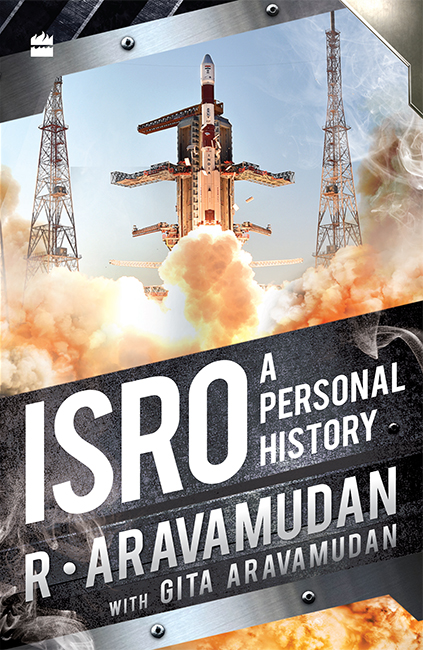

ISRO

A PERSONAL HISTORY

R. ARAVAMUDAN

WITH

GITA ARAVAMUDAN

To all my colleagues at ISRO, present, past and future, my

co-travellers on Indias incredible journey into space

Contents

28 September 2014

M y laptop screen glowed with the colours of Mars. I could hardly believe it. We had done it! Mangalyan, Indias first home-grown mission to Mars, was a spectacular success. I was actually looking at an image captured by the Mars Colour Camera (MCC) we had built and mounted on our own Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM).

MOM had been launched from Sriharikota ten months ago, on 5 November 2013. My wife Gita and I watched the spectacular take-off from the new state-of-the-art control centre. As ISROs workhorse PSLV-C25 soared faultlessly into space, we anxiously watched the flight path on the monitor screen. But the men and women sitting at the consoles were cool and confident the PSLV had proved itself over and over, and this generation had learnt to take it for granted. In any case, the launch was the least of their worries. They knew that over the next ten months they had the much more complicated task of guiding and safeguarding the 500 kg Mars Orbiter as it flew for almost a year through space. And then they had to slide it into a precise orbit around a faraway planet. Almost all the ISRO centres were involved in this complex mission. Ground stations across the world were tracking it finally, the eyes of the world were on us.

I was now witnessing the final spectacular success of that Mission. No other Mars Mission had succeeded in its very first attempt. ISRO had developed all the technology from scratch. And we had used so many innovative ideas for cost cutting and fuel saving. Now our success was splashed across space.

Thirty-five years ago when we anxiously watched the take-off of our first SLV, we could never even have imagined a mission of this scale.

10 August 1979

By the second half of the 1970s, we were on a high we were getting ready to launch SLV-3, our first home-grown launch vehicle.

We were not a battle-hardened team of professionals with scores of successful rocket and satellite missions behind us. But we were young, highly motivated and hardworking. None of us had been part of an actual satellite launch, and now we were thirsting to realize our pre-flight dreams.

There were quite a few sceptics, in our midst and around us. Indians had never done such a thing on their own ever before, they said. What could a bunch of youngsters do? Besides, werent we reinventing the wheel? But the organization and the government were solidly behind us, and supported our teams morally and materially.

Finally, a good five years after the date originally proposed by Dr Vikram Sarabhai, the SLV-3 was ready and assembled for flight on the pad at Sriharikota. Abdul Kalam, a close friend and colleague, was on tenterhooks. This was his first major project.

Whenever Kalam was asked to define the success criterion of the project, he would say that the very act of bringing the assembled vehicle on to the launch pad constituted 50 per cent success. He would go on to assign success percentages to various events, such as the take-off, first stage function, second stage function and so on until the actual injection into orbit of the satellite.

Would this, our first launch, score on all counts?

The launch was scheduled for the early morning and I was seated in the control room in front of a console, monitoring the status of the tracking systems the team had built from scratch and installed. Senior colleagues were anxiously watching the progress of the countdown from behind. Kalam was at the mission directors console, busily talking on the telephone to various subsystem specialists. The countdown clock was ticking and Kalam had given the mission directors clearance for the launch.

Things were moving smoothly. The umbilical cable was pulled out and the vehicle was on its own batteries. The countdown edged towards the dramatic last ten seconds. Right on the dot, at count zero, the first stage ignited and the vehicle majestically lifted off. Those of us involved with the launch were intent on our consoles and did not go out to see the take-off.

We heard the mighty roar of the vehicle a few seconds later as the sound took its time to reach us. The burning of the first stage seemed normal. I was watching Kalam for some sign. Had the rocket performed well? After some time, I saw a blank and fixed expression on his face, followed by disappointment. He turned around and made a thumbs-down gesture. Something had gone wrong.

The vehicle went out of control and splashed into the Bay of Bengal at a distance of 560 km from the coast, about five minutes after take-off. Our very first attempt to launch a satellite launch vehicle was a failure, although it was officially dubbed a partial success.

I remember clearly the moment I decided I was going to be a rocket scientist.

The year was 1962. It was just another day at the reactor control division of the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) in Trombay. The excitement of moving to Bombay from Madras and into a very sought-after job had worn off. After two years, my work at DAE had become routine and I was getting fed up of the crowds and the hustle and bustle. I was twenty-four. Restless. And wanting to move on.

I was chatting in the canteen with my friend, also a junior engineer like me. He told me he had heard that a scientist called Dr Vikram Sarabhai, founder of the Physical Research Laboratory (PRL) in Ahmedabad, was looking for volunteers to set up a rocket launch pad in south Kerala. He wanted to form a core group of young engineers who would be sent to the US to train at NASA before they were relocated to Kerala.

Should we volunteer? my friend asked pensively. It all sounds quite vague. But NASA sounds exciting.

Even while he was wondering about it, I had made up my mind. This seemed like a heaven-sent opportunity. First NASA and then back home to south India. What more could I ask for? There was no question. I would try my luck I was volunteering!

Thinking back now it seems almost dreamlike. No recruitment processes, no job interviews nothing. The first recruits for Indias space programme were all young volunteers like me from the premier scientific institutions of the day. And we all just heard about it by word of mouth.

After that everything happened in a rush. When they heard of my decision to volunteer, most of my colleagues thought I was mad. Why on earth would I want to sacrifice a career with steady growth prospects to chase a chimera? I had been directly recruited into DAE after graduating with a first rank from the Madras Institute of Technology, one of the countrys most prestigious engineering colleges in those days. And now I wanted to throw it all away?

The only safety net I had was the fact that the programme was being backed by DAE, so I would continue to be on their payrolls. When I talked to my parents back home they were more concerned about my pay packet. Would I be able to sustain myself? We were a middle-class family and money did not exactly grow on trees. But when they realized how thrilled I was at the thought of going to NASA, they supported me. After all, what was the worst that could happen? I might not be chosen. And if the project failed, I could still go back to my old job as this would be a project done on deputation.