Contents

Guide

Pages

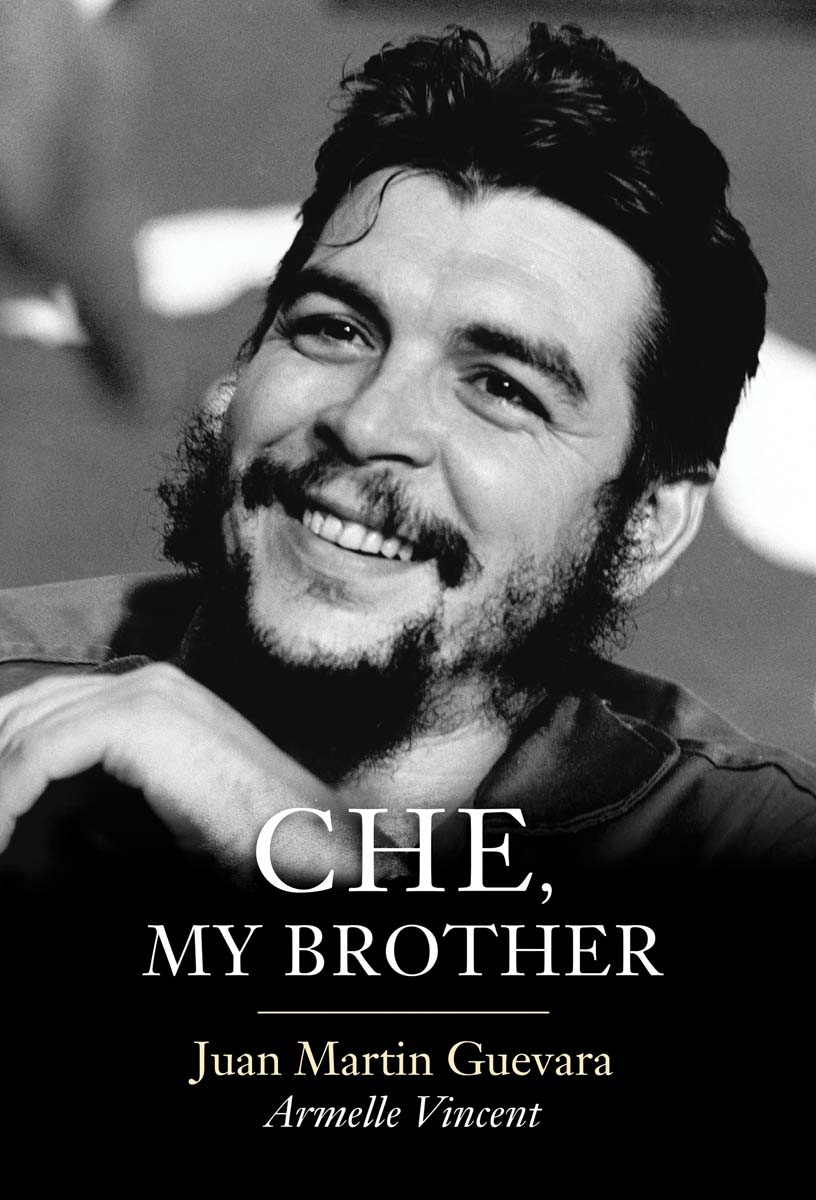

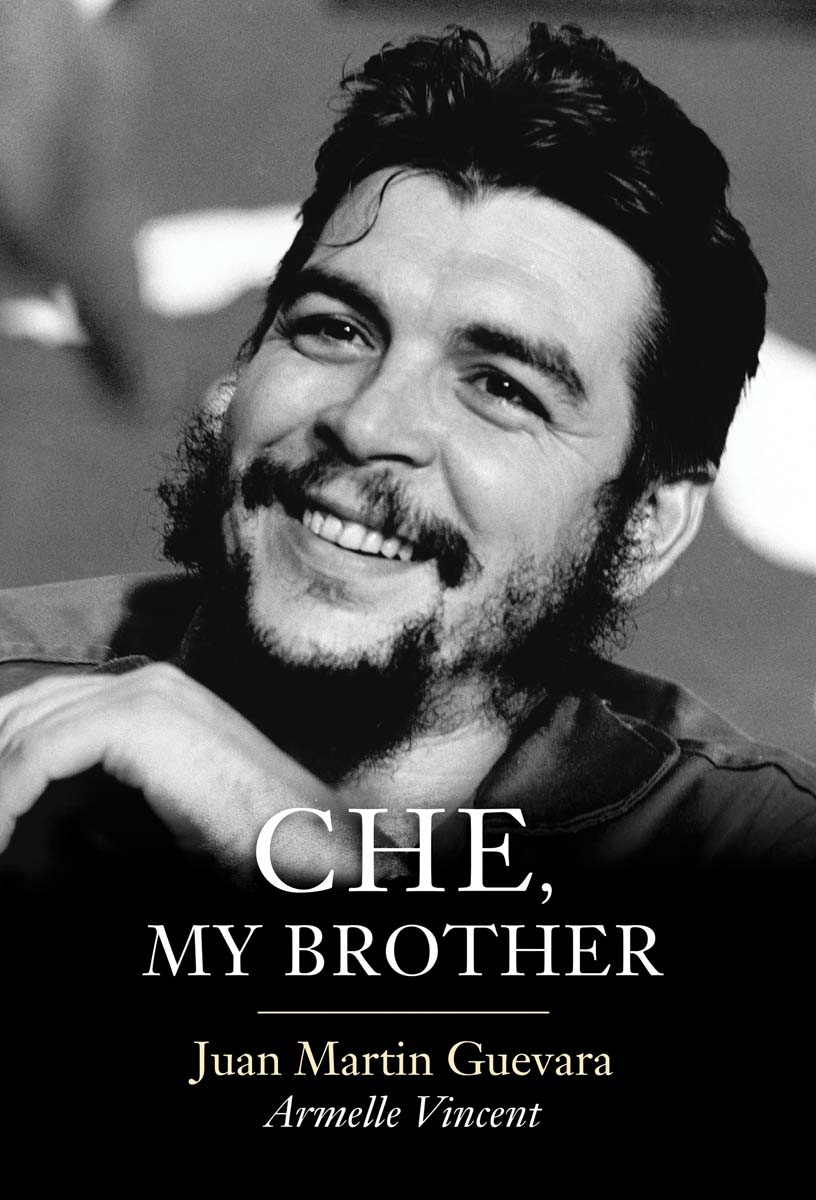

Che, My Brother

Juan Martin Guevara Armelle Vincent

Translated by Andrew Brown

polity

First published in French as Mon frre, le Che, ditions Calmann-Lvy, 2016

This English edition Polity Press, 2017

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-1778-7

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Guevara, Juan Martin, author. | Vincent, Armelle, author.

Title: Che, my brother / Juan Martin Guevara, Armelle Vincent.

Other titles: Mon frere le Che. English

Description: English edition. | Cambridge ; Malden, MA : Polity, 2017. |

Includes bibliographical references and index. | Original French title from Amazon view of online title page.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016041405 (print) | LCCN 2017000120 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509517756 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509517770 (Mobi) | ISBN 9781509517787 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Guevara, Che, 1928-1967. | Guerrillas--Latin

America--Biography. | Cuba--History--1959-1990. | Latin

America--History--1948-1980. | Guevara, Che, 1928-1967. | BISAC: POLITICAL SCIENCE / Political Freedom & Security / Terrorism.

Classification: LCC F2849.22.G85 G7613 2017 (print) | LCC F2849.22.G85 (ebook) | DDC 980.03092 [B] --dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016041405

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Acknowledgements

To all the companions who, faithful to the spirit of Che, have had the courage to persevere in the struggle for the creation of a new society, rich and fair.

To my fortunate encounter with Armelle that made it possible for me to write this book dedicated to young people, and to the certainty that the world has other Che(s) waiting for the right moment to rise up.

Juan Martin Guevara

1

La Quebrada del Yuro

I waited forty-seven years before going to see the spot where my brother Ernesto Guevara was murdered. Everyone knows he was killed by a cowards rifle on 9 October 1967 in a shabby classroom of the village school in La Higuera, an isolated hamlet in South Bolivia. He had been captured the day before at the bottom of the Quebrada del Yuro, a bare ravine where he had entrenched himself after realizing that his sparse band of guerrillas, weakened by hunger and thirst, was surrounded by the army. They say he died with dignity and that his last words were Pngase sereno y apunte bien. Va a matar a un hombre (Calm down and take good aim. Youre going to kill a man). Mario Tern Salazar, the unfortunate soldier appointed to do the dirty work, was shaking. True, Che had for eleven months been public enemy number 1 of the Bolivian army, perhaps even of the entire American continent, but he was a legendary opponent, a mythical figure covered in glory, known for his sense of justice and fairness and also for his immense bravery. What if this Che, gazing unblinkingly at him with his big deep eyes without seeming to judge him, really was the friend and defender of the humble rather than the blood-stained revolutionary portrayed by his superiors? What if his disciples, said to be loyal to a fault, would one day decide to track him down and avenge Ches death?

Mario Tern Salazar had needed to get drunk before he could find the courage to pull the trigger. When he saw Che sitting calmly, waiting for the inevitable, he rushed out of the classroom, bathed in sweat. His superiors forced him to return.

My brother died standing. They wanted him to die sitting down, to humiliate him. He protested and he won this last battle. Among his many qualities, or talents, he could be very persuasive.

I bought a new pair of sneakers to get down to Quebrada del Yuro. Its a deep gorge, falling away abruptly behind La Higuera. It was very difficult, very painful for me to be here. Painful, but necessary. This pilgrimage was a project Id been carrying around with me for years. It had been almost impossible to come here any earlier. In the first years following Ches death, I was too young, not quite prepared psychologically. Then Argentina turned fascist and repressive and I languished for nearly nine years in the jails of the military junta that seized power in March 1976. I learned to lie low: in the political climate of my country, it was for many years dangerous to be associated with Che Guevara.

Only my brother Roberto came to the area in October 1967, sent from Buenos Aires by the family to try and identify Ernestos body once the news of his death had been announced. He returned deeply shocked and bewildered: by the time he arrived in Bolivia, the remains of our brother had vanished. The Bolivian soldiers led Roberto a merry chase, sending him from one city to another, changing their story every time.

My father and my sisters Celia and Ana Maria never had the strength to make the journey. My mother had succumbed to cancer two years earlier. If she had not already been in the grave, Ernestos assassination would have finished her off. She adored him.

I drove here from Buenos Aires with some friends. A journey of 2,600 kilometres. In 1967, we did not know where Ernesto was. He had left Cuba in the greatest secrecy. Only a few people, including Fidel Castro, knew that he was fighting for the liberation of the Bolivian people. My family was lost in conjectures, imagining him to be on the other side of the world, in Africa maybe. In reality, he was only thirty hours away from Buenos Aires, where we lived. We would learn years later that he had travelled via the Belgian Congo where, with a dozen or so black Cubans, he had gone to support the Simba rebels.

On the crest of the ravine, Im approached by a guide. He doesnt know who I am and I dont want to reveal my identity. He demands that I give him some money to show me where Che was captured the first sign that my brothers death has been turned into a business venture. I am outraged. Che represents the complete opposite of sordid profit. The friend who has accompanied me here is furious; he cant stop himself from telling the guide who I am. How dare this guide try to get money out of Ches brother just when he is coming to pay homage for the first time at the site of his fatal defeat? The guide steps back with reverence and stares at me wide-eyed. Its as if he has just seen an apparition. He apologizes profusely. Im not listening. Im used to it. Being the brother of Che has never been a trivial matter. When people learn who I am, theyre dumbstruck. Christ cant have any brothers or sisters. And Che is a bit like Christ. In La Higuera and Vallegrande, where his body was taken on 9 October to be displayed to the public before disappearing, he became San Ernesto de la Higuera. The locals pray before his image. I generally respect religious beliefs, but this one really bothers me. In the family, since my paternal grandmother Ana Lynch-Ortiz, we havent believed in God. My mother never took us to church. Ernesto was a man. We need to pull him down off his pedestal, give life to this bronze statue so we can perpetuate his message. Che would have hated being turned into an idol.