Praise for

BRIGHT BOULEVARDS, BOLD DREAMS

Bright Boulevards, Bold Dreams brims with personal accounts of black Hollywood in the making, from its beginnings in the early 1900s to the civil rights era of the 1960s. [It] is a valuable historical document, entertaining and educational, uplifting and sad.

Los Angeles Times Book Review

Nobody tells the story of Black Tinseltown like Donald Bogle.

Essence

It's the story behind the camera, the tales of nightclubs, agents, and the social scene, that makes [Bright Boulevards, Bold Dreams] stand out. Highly recommended.

Library Journal

Shameful, funny, enlightening, and sobering, this tale of movieland's dark side is a must-read for any student of film history.

Entertainment Weekly (Editor's Choice)

Bogle's book soars. His tales are captivating.

Contra Costa Times

Bright Boulevards, Bold Dreams is a fascinating, anecdote-filled history of black Hollywood in the segregation era and a delicious compendium of tasty tidbits regarding interracial affairs, mixed-race social events, extravagant lifestyles and careers gone awry.

The Philadelphia Inquirer

Bogle's lively style and his many anecdotes will entertain and inform film students and black history buffs alike.

Publishers Weekly

This is a brilliant, detailed exploration of African Americans in cinema spanning sixty years. At times, Bright Boulevards, Bold Dreams reads like an intellectual gossip column, and at other times it is an uplifting display of many key African Americans in power and in the world of intelligentsia. A bright and bold work that all Americans should read.

Black Issues Book Review

[Bogle writes in a] lively, scholarly style [and] so thoroughly conveys Central Avenue's charms, you can almost hear the trolleys rolling down the street and the laughter ringing out of nightspots.

The Washington Post

Bogle is a modern-day griot, preserving the legacy of black actresses and actors through his books, lectures, and passion. In Bright Boulevards, Bold Dreams, Bogle continues to reveal a part of film history that is rarely talked about or documented.

New York Daily News

[Bright Boulevards, Bold Dreams is] filled with amusing and telling details.

Variety

[An] altogether fascinating book.

Raleigh News & Observer

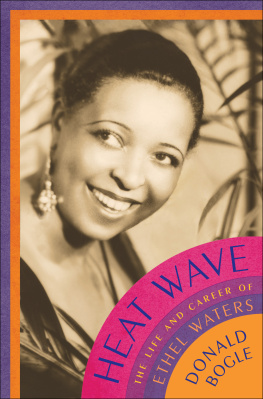

ALSO BY

D ONALD B OGLE

Primetime Blues:

African Americans on Network Television

Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks:

An Interpretive History of Blacks

in American Films

Dorothy Dandridge:

A Biography

Brown Sugar:

Eighty Years of America's Black Female Superstars

Blacks in American Films and Television:

An Illustrated Encyclopedia

TO PELE AND LORI

TO AYANA AND HASSAN

TO MY GOOD FRIENDS

HARRY FORD, ENRICO PELLEGRINI ,

AND THE ONE AND ONLY

ISABEL WASHINGTON POWELL

AND WITH LOVE TO THE MEMORY

OF THREE EXTRAORDINARY WOMEN:

ROSLYN WOODS BOGLE

AND THE TWO ACTRESSES WHO FIRST LED

ME TO BLACK HOLLYWOOD:

FREDI WASHINGTON

AND VIVIAN DANDRIDGE

INTRODUCTION

L ong agowhen I was just beginning to research the work of African American performers in HollywoodI made a trip to Stamford, Connecticut, to interview actress Fredi Washington. She had been retired from show business for decades. But in 1934, Fredi Washington had gone to Hollywood to appear in Imitation of Life and afterward became one of the most talked about black actresses working in the movies. For black America, she was the black girl who looked white or the girl with the boy's name. Her movie career, however, had been something of a dead end because Hollywood didn't have a place for her. By this time in her life, Washington wasn't exactly a recluse. But she didn't see many people, other than old friends, and she clearly didn't need any kind of spotlight to go about the business of her life. Nor was she an actress consumed with the past. Yet, through Bobby Short, she had said she was interested in meeting me. I wasn't sure what to expect. Would she be bitter about Hollywood? Would she be unwilling to delve deeply into that period of her life?

That afternoon, I found Fredi Washington living simply and very comfortably in a well-furnished apartment with a bit of show business memorabilia around but not much. Slender and casually dressedwith piercing blue-green eyes that could look right through youshe still possessed the elegant good looks and stylish sophistication that had made her so distinct in the past, and her mind was as sharp and quick as ever. By then, I had already interviewed a number of entertainers, but I don't think I had ever met any as intelligent as Washington. Or as fascinating.

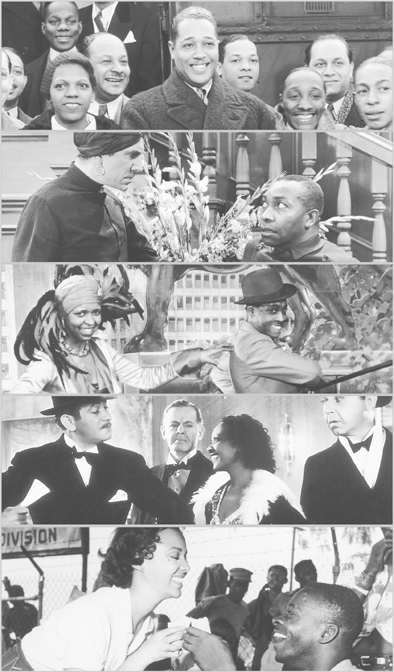

As she talked about her career, an array of images floated by: the days of the Harlem Renaissance and New York theater from the 1920s into the 1950s. She had rich, evocative memories of a gallery of African American stars of an earlier time: Paul Robeson, Ethel Waters, Duke Ellington, Josephine Baker, Alberta Hunter, and her own sister, actress Isabel Washington Powell. The New York entertainment scene on which she commented was not unfamiliar to me. But when she discussed her time in Hollywood, something else came to light that I had not really expected. Like everyone else, I had always thought of classic Hollywood in terms of those golden age icons: stars such as Garbo, Gable, Harlow, Tracy, and later Monroe, Taylor, Brando, and Dean. There had been restaurants such as The Brown Derby and Romanoff's, nightclubs such as the Mocambo and Ciro's, hotels such as The Ambassador and The Beverly Hills, a famous street, Sunset Boulevard, and an even more famous intersection, Hollywood and Vine.

But Washington spoke of another Hollywood, which most people probably didn't even know existed: of a part of Los Angeles where many African Americans had once resided, first the Eastside, later the Westside. Her eyes lit up when she mentioned the grand thoroughfare Central Avenue, where black nightclubs flourished and where the Dunbar Hotel, home to the black elite, stood like a mighty fortress. There had been glittering and unpredictable personalities, such as Bill Bojangles Robinson, Hattie McDaniel, Louise Beavers, Stepin Fetchit, and Nina Mae McKin-ney. Slowly coming into view was a vision of the old Black Hollywood, which was both a distant place and a distant frame of mind. During the several hours I spent with her, Washington transported me to another age.

She brought into sharper focus a world of which I had caught a glimpse earlier when I had interviewed Vivian Dandridge, the older sister of Dorothy, who then lived on Manhattan's Upper West Side. Having spent most of her childhood and her young adulthood in the movie capital, Vivian had experienced the giddy heights of success and the devastating, heartbreaking effects of failure. She spoke as if she had left Los Angeles on the runfor her sanity and her life. Yet, oddly, she had vivid, sweet memories of Black Hollywood. Both Dandridge and Washington offered me a bird's-eye view of the black movie colony's way of life during the first half of the twentieth centuryand the glamour ideal that the town and much of the entertainment industry in general valued. Each understood the relentless drive and energy it took to work and ultimately survive in the town. Each was shrewdly aware of movieland culture: the unwritten values and rules that governed the lives of so many. And though each had left, both understood the strangely magical magnetic force that drew so many entertainers to Hollywood.