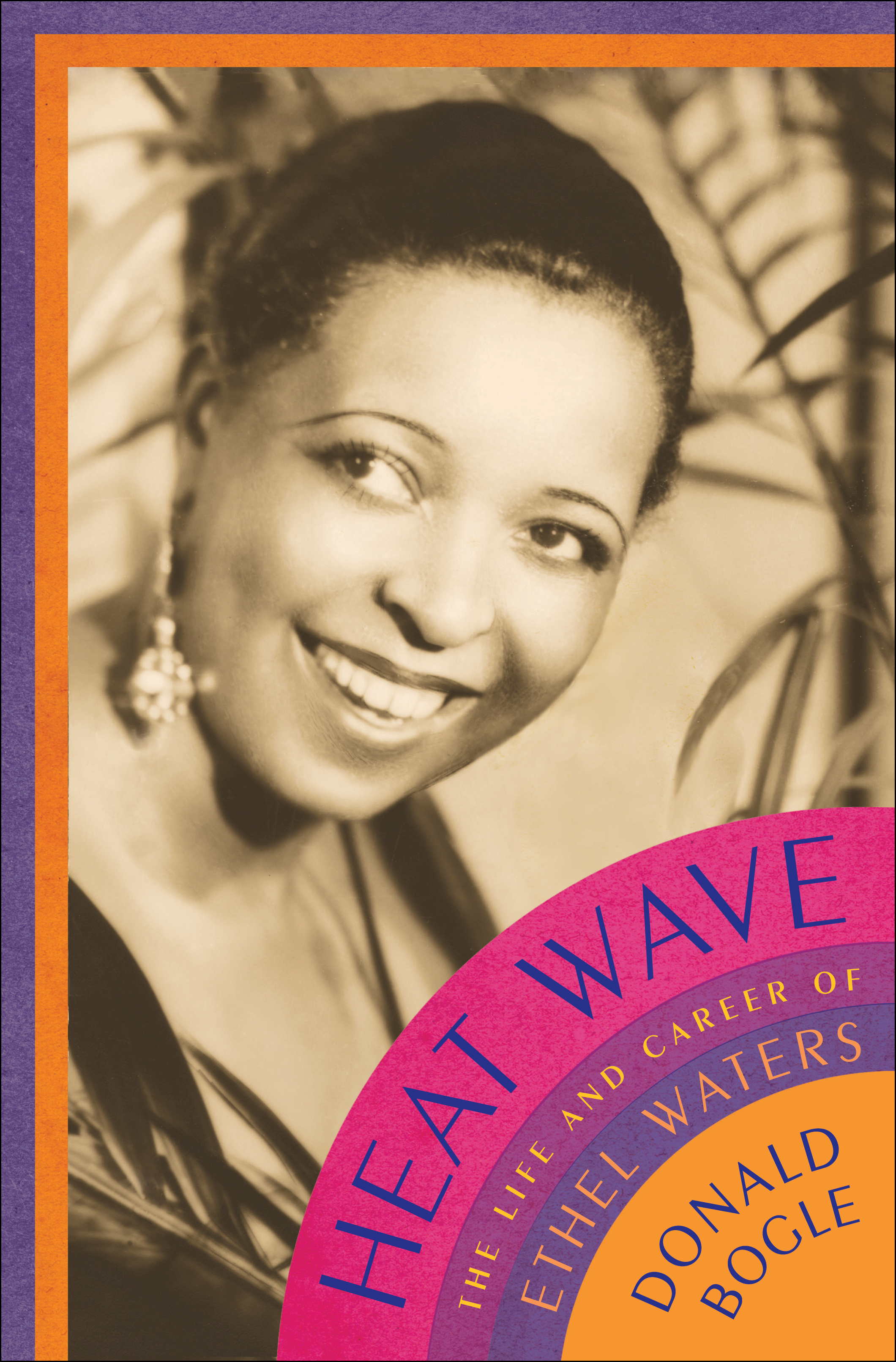

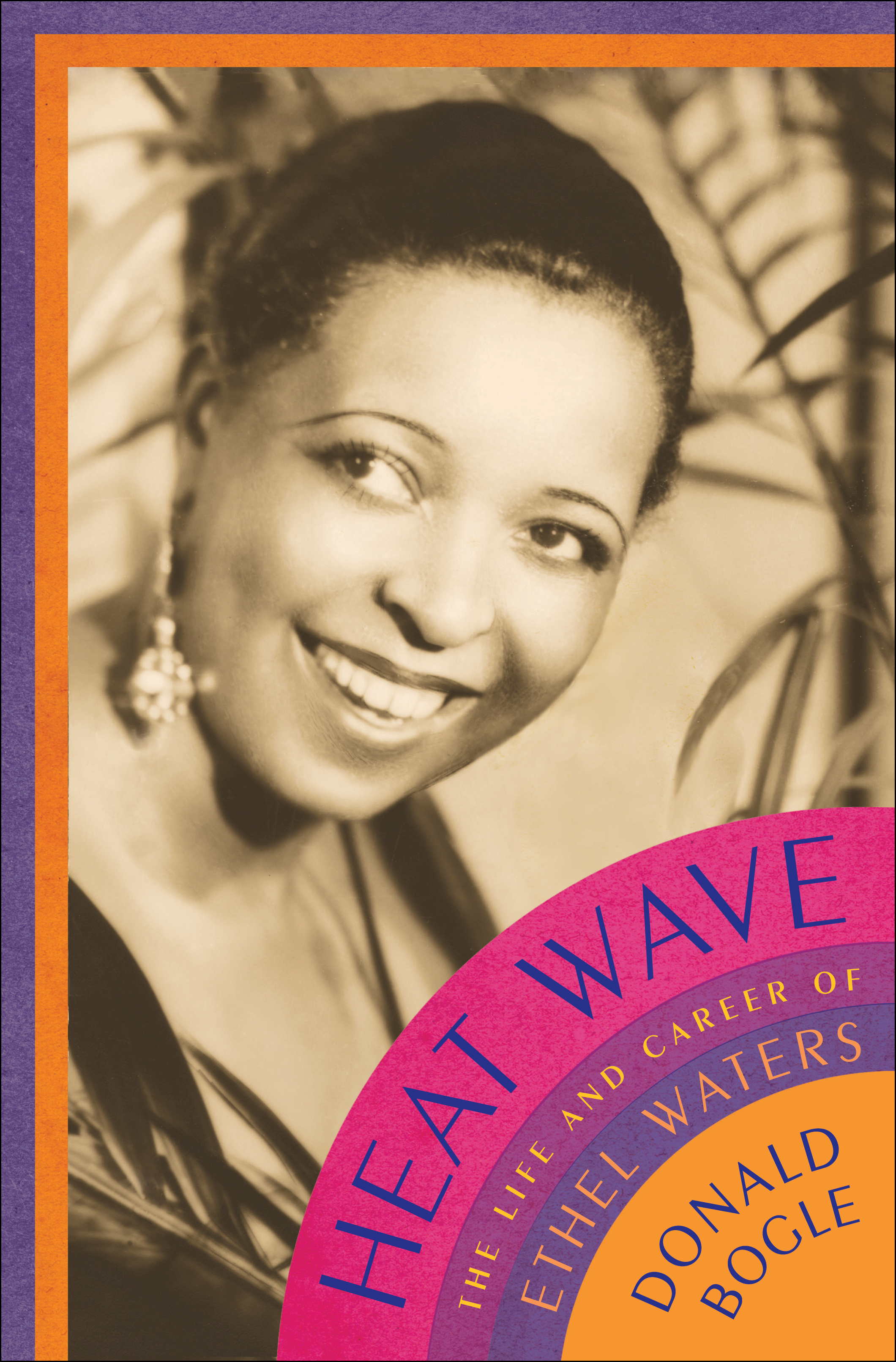

Heat Wave

The Life and Career of

Ethel Waters

Donald Bogle

To Catherine Nelson, my beloved Kay

And to my parents, Roslyn and John, and my brother John, and my cousin Clisson, now all gone but forever in my heart

Contents

W ith only a few minutes to curtain time, Ethel Waters stood in the wings of Broadways Empire Theatre, ready to take her place onstage on the evening of January 5, 1950, in the drama The Member of the Wedding . Though nervous, she knew she could not let her nerves get the best of her. After all, she had made countless entrances countless nights before in countless theaters and nightclubs around the country. Her long years of experience had taught her how to gauge an audiences mood, how to play on or against an audiences expectations, while always remaining in character. But for a woman who had been in show business for some four decades, first appearing in tiny theaters, sometimes in carnivals and tent shows, often in honky-tonks, and then in the clubs in Harlem and on to Broadway and Hollywood, there was much, almost too much, at stake tonight. This opening night was different from all others.

The past five years had been hell. Engagements had fallen off. Friends had gone by the wayside. Lovers had disappointed her. Worse, she was broke. The Internal Revenue Service was hounding her for back taxes. Lawyers and accountants were scrambling to get her finances in order. And there had been the physical ailments, the shortness of breath, the problems walking and standing, the sharp pains that suddenly pierced her back and abdomen, and the great weight gains. At one point in her career, she had been called Sweet Mama Stringbean. She had been so sleek and slinky that in London the Prince of Wales had made return visits to see her perform at one of the citys chic supper clubs. But now she weighed close to three hundred pounds.

Then there was show business gossip. Almost ten years had passed since she had appeared in a major Broadway show, and some people wondered if she still had what it took. Word had spread throughout entertainment circles of her explosive outbursts on the movie set of Cabin in the Sky , which had led to her being blacklisted from Hollywood for six years. Her temperamentthe quarrels, the fights, the foul languagewere almost legendary now. If any man or woman ever crossed her or even looked like they might do so, she hadnt hesitated to tell them all to go straight to hell. No bitch or son of a bitch was ever going to tell her what to do. Though she had been able to defy the odds and come back strong in the movie Pinky and would even win an Academy Award nomination, it was still a struggle to crawl back to the top. Broadway was the place Ethel Waters respected most. She also wanted to show the young playwright, a mere slip of a girl named Carson McCullers, that her faith in Waters was justified, that indeed the notoriously difficult old star could breathe life into McCullers character in The Member of the Wedding , the one-eyed cook Berenice Sadie Brown.

Her current problems, in some ways, were nothing new. Her life had already been a turbulent, stormy affair, with frightening lows and extraordinary highs. She had grown up in the depths of poverty in Chester, Pennsylvania, and the nearby city of Philadelphia. Almost on a lark, she had started singing, and the effect on audiences had been startling as she worked her way up on the old chitlin circuitBlack clubs and theatersaround the country where she was first known for her sexy bumps and grinds and her dirty songs. Most of her life had been spent on the road. Yet in the early 1920s, she had been one of the first Black performers in Harlem whom whites from downtown rushed to see. Then through the 1920s and into the 1930s, she had made records that shot to the top of the charts, first with Black record buyers and later with white ones. With such songs as Shake That Thing, Am I Blue? and Stormy Weather, as well as the later show tunes Heat Wave and Taking a Chance on Love, she had changed the sound of popular song, ushering in a modern style of singingand a modern, independent tough-girl persona.

At a time when African American entertainers, especially women, found doors closed to them and one barrier after another in front of them, she had audaciously transformed herself from a blues goddess into a Depression-era Broadway star in As Thousands Cheer , a white show in which she was the only major Black performer. She became known as a woman who could do everything. She could sing, dance, and act with the best of them. Later, on the Great White Way, she had done the impossible: she had a brazen, unexpected triumph as a dramatic star in Mambas Daughters . Never had Black America seen a heroine quite like her: stylish, bold, daring, assured, assertive. Still, throughout, she had been subjected to all types of racial and sexual slights and indignities. Traveling through the South during much of her career, she came face to face with the most blatant forms of racism. The body of a lynched Black boy had once been dumped into the lobby of a theater where she performed. Even in sophisticated New York, one white costar always greeted her by saying, Hi, Topsy. At another time, her white costars were said to have balked at having to take curtain calls with her. That may have bothered her, but she ended up walking away with the show itself. Sweet revenge, but it had taken a toll on her.

Through the years, there had also been the complicated relationships with her mother and her sister. Then there was a series of bawdy love affairs and steamy liaisons. A steady stream of men had rolled in and out of her life, some boyfriends, some husbands, others lovers who were known as husbands, men whom she had spent lavishly on, buying them cars, clothes, diamond studs, putting them on her payroll. One had robbed her blind and put her in the headlines. And there had been female lovers, the gorgeous girlfriends who sometimes appeared in her shows, sometimes worked as her secretaries and assistants, sometimes stayed in her homes.

There had also been the heated feuds, quarrels, and confrontations with such stars as Josephine Baker, Bill Bojangles Robinson, Billie Holiday, and Lena Horne as well as with nightclub owners, managers, agents, directors, and producers. Sometimes the battles were professional. Other times, they were personal. She had been cheated out of money, and she felt betrayed and abandoned in the backbiting, backstabbing environment of show business. In time, at the root of many battles was her growing paranoia and deep suspicion of most of the people around her. Still, some of the most accomplished and famous artistic figures and movers and shakers of the twentieth century had been eager to work with her: Duke Ellington, Irving Berlin, George Balanchine, Harold Arlen, Elia Kazan, Count Basie, Darryl F. Zanuck, Vincente Minnelli, Fletcher Henderson, Andy Razaf, Moss Hart, Sammy Davis Jr., Benny Goodman, Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, James P. Johnson, Dorothy Fields and Jimmy McHugh, Guthrie McClintic, Harold Clurman, Carson McCullers, Julie Harris, and later Joanne Woodward, Harry Belafonte, and others.

But while many in show business were quick to call her a hot-tempered bitch on wheels, she was also known as being pious and extremely religious. She kept a cross and a framed religious poem in her dressing room, and before each performance, she bowed her head in prayer. Still, as one performer said, that never stopped her from cussing you out.

That night at the Empire Theatre, as the stage manager called, One minute, Ethel Waters took her place onstage. She carefully adjusted the patch on her eye. She also must have taken one long deep breath, silently prayed, and realized that everything in her lifethe troubled early years, the reckless relationships, the unending fears and doubts, the constant stomach problemshad led to this moment.

Next page