Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

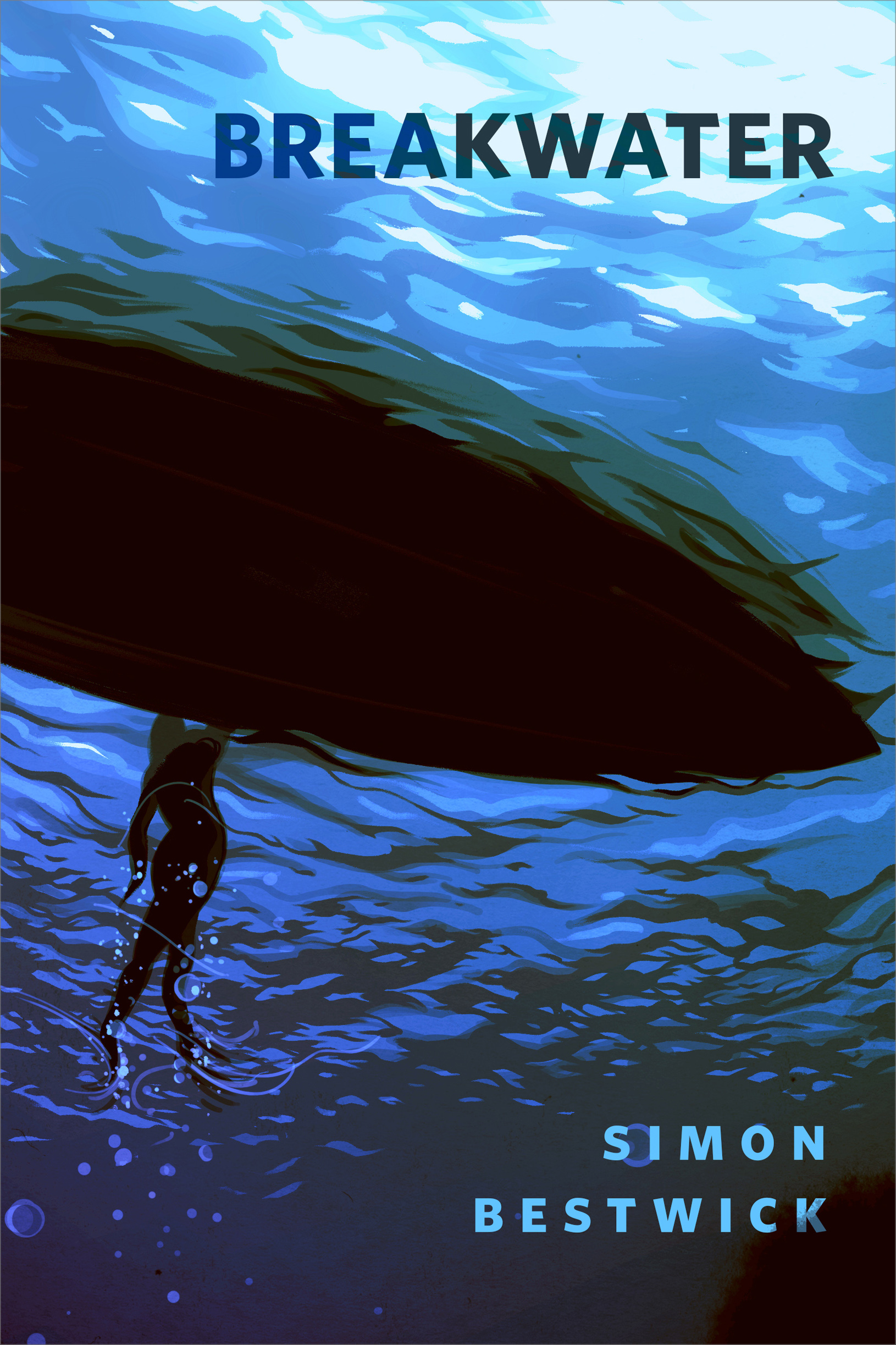

Breakwater

by Simon Bestwick

I. HMS Dunwich

The wreck-buoy bells rang in the mist, among the low-tide ruins. Hunched against the cold, Cally steered the dinghy between shoal and brickwork and the hulks of rusting cars.

Dull, fitful lights gleamed in the fog. Their maintenance was a low priority, as most of the pumphouse and lightship crews were airlifted on and off, but Cally had never liked helicopters; give her a small boat any day. You always were awkward, Ben would have said.

The surviving parts of the city loomed like a black ridge of shadow to Callys right. The cliffs of the Suffolk coast were essentially banks of compacted gravel and sand. Even the gentlest tides wore them steadily away, and when storms raged or flood waters rose, another piece of land fell into the hungry waves.

There wasnt as much recent wreckage farther out, and the watereven at low tidewas deeper. Cally sailed over houses, streets, and churches. A foghorn sounded in the mist.

A bigger, more powerful glow shone through the fog; Cally steered towards it, opening the dinghys throttle.

The ship emerged from the mist. Originally it had been painted red, but was now streaked green and orange by weed and rust. It rocked gently in the swell, tugging at its anchor chains. Above the peeling characters LVR36 on its side (light vessel relays were rarely graced with a proper name) a crewman waved from the deck.

On the ships seaward side, a wooden pontoon, secured to the hull by ropes and chains and kept afloat by a score of buoys, served as a crude but effective staithe. Cally moored the dinghy and climbed out. The boards were spongy and damp.

The docking station stuck out of the water by the pontoon, its side covered with barnacles, limpets, hanging rags of mussels and weeds. Around its top, at right angles to one another, were four circular hatches, one of which directly overlooked the staithe. Cally pulled on her thick gloves before climbing the ladder bolted to the side; the rungs were jagged with rust. At the top she spun the wheel in the centre of the recessed hatch and pushed it open.

On the other side of the airlock, a second ladder led down to the bottom of the forty-foot cylinder. The dull sun glimmered through the toughened glass panels in the hatches. Waves slapped against the modules hull as Cally climbed down, so that it hummed like a struck bell.

Another airlock led into another metal cylinder, laid flat rather than on end. Rows of toughened glass portholes ran along the sides. Outside, fish wove in glittering swarms through the ruins of homes, cars half-buried in silt, the hulls of boats brought to grief.

Ben would have loved swimming through this seascape, studying whatever had made its home among the ruins. But Suffolk wasnt like the Greek islands hed lovedno white, sugar-soft sand to make love on, naked and shiny with lotion. Try that here, youd end up with pneumonia. She carried on down the module to the transport station.

The station was a wide, squared-off structure, in which four golf carts stood with their bare wheels slotted into mounted rails. A plaque was mounted on the wall:

HMS Dunwich

Permanent Underwater Modular Platform

Cally saw herself in the polished brass: a small, lean woman in her late forties, deep red hair and a strong-boned face. Jeans, sweater, biker jacket, a grey butcher-boy cap. Out of place on Dunwich, but perfect for Breakwater.

The golf carts had no steering wheels, only half a dozen numbered buttons. Cally pushed one and leant back in the cart as it whirred along the rails, out of the station.

Callys ears popped as the cart travelled down the tunnel from the station, down the slope of the seabed. The view outside the windows dimmed and what submerged wreckage could be seen was sparser, more heavily overgrown.

The cart halted in another station. Cally opened the floor hatch and climbed down into the bridge.

The bridge was sixty feet across and thirty high; a broad railed walkway ran around it halfway up, where Harkness sat in her captains chair. The station commander glanced up, grunted, Doctor McDonald, and looked away.

Harknesss dismissive greeting was a ritual now, albeit one that never failed to piss Cally off. You wouldnt have this place without me, without Ben, she often felt like shouting. None of this would exist. But her position here, all she had left of what she and Ben had tried to build, was allowed her less because shed created the pumphouses than because accommodating her was no trouble. (Although occasionally, even Harkness would have grudgingly admitted, she was useful.)

So, as always, Cally said nothing and plodded across the bridge, boots clanking on the steel deck-plates. She zipped up her jacket; with a dozen wall fans in operation to prevent the computer systems overheating, the bridge was always cold. There was a low hubbub of human and electronic chatter, and a faint smell of rust and sweat.

Cally sat down at her desk in the corner. The transmitter had been automatically broadcasting throughout the night while shed been ashore, the hydrophones recording. She uploaded the MP3 files to her laptop and skimmed through them, watching the recordings peaks and troughs. By now she was used to the seas speech patternssonar echoing off fish shoals, the clicks and whistles of dolphin pods, the dull thuds of mines and depth charges, the remorseless rise and abrupt peak of a Chorale. Nothing new; no answer to the calls she sent, over and over, into the depths.

Maybe there never would be. Maybe no-one listened, or no-one who cared. She wished for Ben, as she did a dozen times a day even now; for a moment, she almost felt his warm hand on hers. But only almost. Never truly. And that was never enough.

Cuppa, maam? A fresh-faced naval rating proffered a steaming mug.

Thanks. She smiled at him and he flushed a little, looking down. He was about twenty, less than half her age. Cally wondered if she should feel flattered.

The boy glanced over at Harkness, who was deep in conversation with Sub-Lieutenant Cannonbridge, the Gunnery Officer. Can I, um, ask you something? He was fair-haired and pale, with a face so unstamped by experience Cally couldnt believe he was old enough to join up.

You can ask, she said.

He blinked. Cally took pity on him. Course you can, love, she said. Love. That had slipped out before she could stop it. He turned even redder. Ask away, she said, Mister

B-Baker, he stammered. Is it true you built this place?

No. Baker blinked some more. I designed it with my husband. Of course, it was a lot smaller then.

You designed Dunwich? He looked thoroughly awed. Bless him. Wow.

HMS Dunwich: the name stung. Cally shook her head. Itll always be Breakwater to me. Thats the name Ben gave it.

Ben?

My husband. She nodded around the bridge. This was Breakwater this, the module upstairs, a couple of others. They towed it out here on floats and sank it. And we showed them it could work.