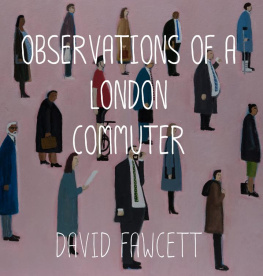

Its almost 11am and the sound of horses hooves echoes down The Mall. The horses are each wearing a breastplate and carrying a soldier dressed in a red tunic with a white-plumed helmet: theyre the Queens Life Guards and this is the daily Changing of the Queens Life Guards, one of Londons most famous (and photographed) ceremonies. Youll find some photos of the Life Guards among these pages but this is a book about so much more than a tourism tick-list of the British capitals highlights.

Our goal was to chronicle a day in the life of this great city from the perspective of a photographer who knows and loves it. We wanted to present not just the famous sights but also Londons daily rhythms as a local would experience them. The book is loosely organised according to the passage of a day and night in the city: we start with a brave early-morning swim in the Serpentine lake of Hyde Park and finish with a night of live music and dance in south London. Along the way we follow the photographer on his peregrinations through Londons diverse neighbourhoods, exploring their signature experiences, from tailoring and high finance to famed food markets, hidden gardens, local pubs and Londons great galleries and museums. It would be impossible to capture all of Londons incomparable variety but readers will discover a side to London beyond the famous sights.

For a task of this scale, we sought a photographer for whom London was not just home, but a source of inspiration. Mark Chilvers who lives in Camberwell, south London took his first portrait at the age of six and it was the start of a journey that led to him becoming a staff photographer at the Independent newspaper (then based in Canary Wharf). For me, says Mark, photography is a way of slowing down to observe the world around me, while also asking myself to make creative sense of the citys chaos. Helping Mark make sense of London was caption-writer Joe Bindloss, a Lonely Planet writer and editor whose first taste of London was a childhood living on the Caledonian Road. As well as writing about London, Joe has written for more than 50 guidebooks to Asia, Europe, Africa and Australia but between overseas hops he can often be found close to home in the ocakba (Turkish grill houses) of northeast London.

Between them, they photographed and described all these facets of London life. The result is this chronologically-ordered visual odyssey through one of the worlds great cities, a taste of London that may give first-time visitors fresh ideas of what to see and do, and also inspire long-time lovers of London to make another trip to The Big Smoke.

The origins of the full English sausage, eggs, beans, bacon, toast and tea are lost in time, but its reputation as the chosen breakfast of the working classes is a relatively new development. Before the 17th century, treats such as bacon and sausage were the preserve of the wealthy upper classes.

Londons working-class cafes do a lively trade in hearty breakfasts for pensioners, who come to socialise and recapture the nostalgic simplicity of days past. The term greasy spoon became mainstream in London during the 1950s, imported by soldiers who served with American GIs on the battlefields of Europe.

Green and pleasant Clapham Common was originally well outside Londons metropolitan sprawl. The first house on the Common was built by parliamentarian William Hewer; the diarist Samuel Pepys died here as a houseguest in 1703, having come to paradisical Clapham to convalesce in the healthy fresh air.

The sweeping curve of Regent St was designed by Sir John Nash in 1825 as a picturesque promenade for the Prince Regent, who lived at nearby Carlton House. Its appearance is little changed, though Quadrant Colonnades was demolished in 1848 because shopkeepers were outraged by the preponderance of prostitutes.

Swimming in the Serpentine is a London institution, and has been since 1730 when Queen Caroline, wife of George II, snipped a loop of the River Westbourne to create the ornamental lake in Hyde Park. Early patrons used to combine a visit with a trip to the public executions at Tyburn, near the modern-day site of Marble Arch.

As I arrived at the Serpentine the sun was gently rising and a slow but steady gathering of early morning swimmers walked from the Victorian changing rooms to join the swans and ducks for their morning dip. The swans seemed more than happy to share their lake with the men and women of the Serpentine Swimming Club, and one man who came early to take his arthritic dog for a swim told me that it was almost too warm at this time in late summer.

- Mark Chilvers

The Londoners who swim here span the socio-economic and cultural spectrum: black-cab drivers, retired shopkeepers, diplomats, famous Channel swimmers.

Nostalgia is part of the Serpentine Swimming Clubs appeal it is one of the last swimming clubs to still measure races in Imperial yards and inches.

0800: Swimming in the Serpentine is not an activity to be taken lightly. The water temperature only climbs above 15C (59F) for a few months in summer, and swimmers who brave the cold waters without a wetsuit tow a dayglo float in case of sudden cramps.

Compared with Londons other swimming ponds, the allure of the Serpentine has always been distance, 361ft (110m) shared only with fellow swimmers and the odd swan, goose or duck. It was the setting for the marathon swimming and triathlon events during the 2012 Olympics.

Since Christmas Day 1864, members of the Serpentine Swimming Club have been braving the icy waters for the Peter Pan Cup, named for author JM Barrie, who presented the winners cup for nearly 30 years. The lake was one of the magical haunts of Peter Pan, now celebrated as a statue on the Kensington Gardens bank.

![Lander William - The Quality Chop House: [modern recipes and stories from a London classic]](/uploads/posts/book/166130/thumbs/lander-william-the-quality-chop-house-modern.jpg)