Contents

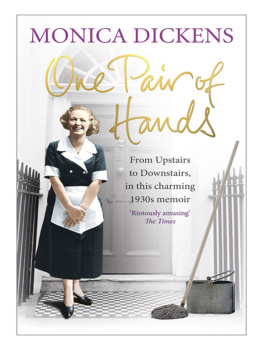

About the Book

Life was a wordless battle of wits between us, with her keeping a sharp look-out for signs of neglect, and me trying to disguise my slovenliness by subterfuge. I became an adept at sweeping dust under the bed, and always used the same few pieces of silver.

Unimpressed by the world of debutante balls, Monica Dickens shocked her family by getting a job. With no experience whatsoever, she gained employment as a cook-general.

Monicas cooking and cleaning skills left much to be desired, and her first few positions were short lived, but soon she started to hold her own. Monica discovered the pleasure of daily banter with the milkman and grocers boy and the joy of doing an honest days work, all the while keeping a wry eye on the childish pique of her employers.

One Pair of Hands is a fascinating and thoroughly entertaining insight into worlds both upstairs and down in the early 1930s.

About the Author

Monica Dickens MBE was born in 1915, and was the great-granddaughter of Charles Dickens. Expelled from St Pauls Girls School, she was then sent to a finishing school in France, before returning home to life as a debutante: The deb scene and the dances were absolute agony. I would look at the waiters and the maids at balls and know for certain that they were having a better time than I was. So I wanted to belong with them, down there where there was a bit of life. And indeed, she then spent two years as a cook and general servant. She later wrote about her experiences in her first book, One Pair of Hands (1939), which made her a bestseller at the age of twenty-two and immediately established her reputation as a writer. In her career she wrote over fifty books, including the Follyfoot novels, and for twenty years wrote a much-loved column for Womans Own. She was also involved with the NSPCC, the RSPCA and the Samaritans. She died in 1992, and is survived by two daughters.

Chapter One

I WAS FED up. As I lay awake in the grey small hours of an autumn morning, I reviewed my life. Three a.m. is not the most propitious time for meditation, as everyone knows, and a deep depression was settling over me.

I had just returned from New York, where the crazy cyclone of gaiety in which people seem to survive over there had caught me up, whirled me blissfully round, and dropped me into a London which seemed flat and dull. I felt restless, dissatisfied, and abominably bad-tempered.

Surely, I thought, theres something more to life than just going out to parties that one doesnt enjoy, with people one doesnt even like? What a pointless existence it is drifting about in the hope that something may happen to relieve the monotony. Something has got to be done to get me out of this rut.

In a flash it came to me:

Ill have a job!

I said it out loud and it sounded pretty good to me, though my dog didnt seem to be deeply moved. The more I thought about it, the better I liked the idea, especially from the point of view of making some money.

My mind sped away for a moment, after the fashion of all minds in bed, and showed me visions of big money furs a new car but I brought it back to earth with an effort to wonder for what sort of a job I could possibly qualify. I reviewed the possibilities.

Since leaving school I had trained rather half-heartedly for various things. I had an idea, as everyone does at that age, that I should be a roaring success on the stage. When I came back from being finished in Paris, I had begged to be allowed to have dramatic training.

Try anything once, said my parents, so off I went, full of hope and ambition, to a London dramatic school. I hadnt been there more than two weeks before I and everybody else in the place discovered that I couldnt act, and, probably, never would be able to. This was discouraging, but I ploughed on, getting a greater inferiority complex every day. Part of the policy of this school is to knock the corners off the girls (not the men, they are too rare and precious). It is only the tough, really ambitious girls who weather the storm of biting sarcasm and offensive personal remarks that fall on their cowed heads. This is a good thing, really, as it means that only the ones with real talent and endurance go through with it to that even tougher life ahead. The uncertain and inept ones like myself are discouraged at the start from a career in which they could never make a success, and so are saved many heartbreaks later on.

Once having made up my mind that I had no vocation, I enjoyed my year there immensely, and walked about the stage quite happily as the maid, or somebodys sister, with hands and feet growing larger every minute. Gazing into a still pool at sunset, or registering grief, fear, and ecstasy in rapid succession, was wonderful fun, too: especially when performed in the company of fifty other girls in rather indecent black tights.

It didnt occur to me that it might be a little irritating for the authorities to have someone trailing unambitiously about in the dust raised by the star pupils. No one was more surprised than myself, therefore, when I found myself thrown out, figuratively speaking, on my ear standing on the pavement with my books under one arm and my black tights under the other.

The next possibility was dressmaking. I dismissed that, too, at once, because it has always seemed to me to be the resort of inefficient, but certainly decorative, society girls, who are given jobs in dress shops, in the hope that they will introduce their rich friends. After that, they stand about the place in streamlined attitudes, wearing marvellous clothes and expressions of suffering superiority.

That didnt seem quite my style, so I turned to cooking. That was the thing which interested me most and about which I thought I knew quite a lot. I had had a few lessons from my Madame in Paris, but my real interest was aroused by lessons I had at a wonderful school of French cookery in London.

I went there quite unable to boil so much as an egg and came out with Homard Thermidor and Crpes Suzette at my fingertips. I was still unable to boil an egg, however, or roast a joint of beef. The simple things werent considered worth teaching, so I had a short spell at a very drab school of English cooking, where there were a great many pupils clamouring for the attention of the two ancient spinsters who taught us. When they hadnt time to tell me what to cook next, it was: Get washed up, Miss Dickens, and Miss Dickens had to clean up other peoples messes at the sink, till, at last, if she was lucky she was allowed to make a rock-cake.

When I told my family that I was thinking of taking a cooking job, the roars of laughter were rather discouraging. No one believed that I could cook at all, as I had never had a chance to practise at home. Our cook, aged sixty-five and slightly touched, had ruled in the kitchen for thirty years and had an irritating tendency to regard the saucepans, stove, and indeed all the kitchen fittings as her own property.

I once crept down there when I thought she was asleep in her room to try out an omelette. Noiselessly I removed a frying-pan from its hook and the eggs from their cupboard. It was the pop of the gas that woke her, I think , for I was just breaking the first egg when a pair of slippered feet shuffled round the door and a shriek of horror caused me to break the egg on the floor. This disaster, together with the fact that I was using her one very special beloved and delicately nurtured frying-pan, upset cook so much that she locked herself in the larder with all the food and we had to make our Sunday dinner off bananas.