Copyright 2011 by Carl Hanser Verlag Mnchen

English translation copyright 2015 by Shelley Frisch

The translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften International

Translation Funding for Work in the Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany,

a joint initiative of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Office,

the collecting society VG WORT, and the Brsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels

(German Publishers & Booksellers Association).

Originally published in German as Dietrich & Riefenstahl: Der Traum von der neuen Frau

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation,

a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton

Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Lisa Buckley

Production manager: Anna Oler

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

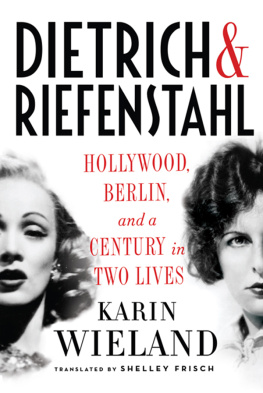

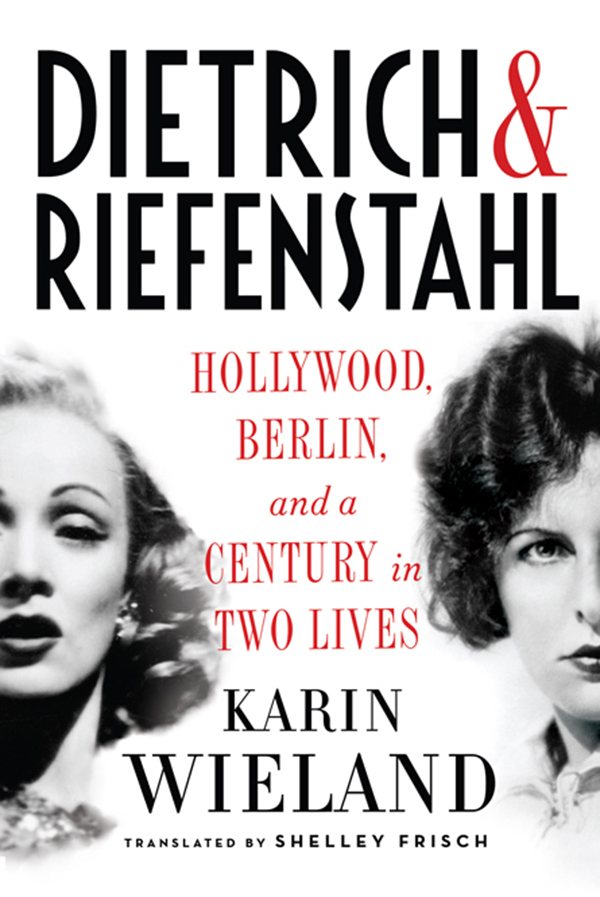

Wieland, Karin.

[Dietrich & Riefenstahl. English]

Dietrich & Riefenstahl : Hollywood, Berlin, and a century in two lives / Karin Wieland ;

translated by Shelley Frisch.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87140-336-0 (hardcover)

1. Dietrich, Marlene. 2. Riefenstahl, Leni. 3. Motion picture actors and actresses

GermanyBiography. 4. Women entertainersGermanyBiography. 5. Women motion

picture producers and directorsGermanyBiography. I. Frisch, Shelley Laura, translator.

II. Title. III. Title: Dietrich and Riefenstahl.

PN2658.D5W5513 2015

791.430280922dc23

[B]

2015026548

ISBN 978-1-63149-096-5 (e-book)

Liveright Publishing Corporation

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

For Andrea

CONTENTS

Leni Riefenstahl

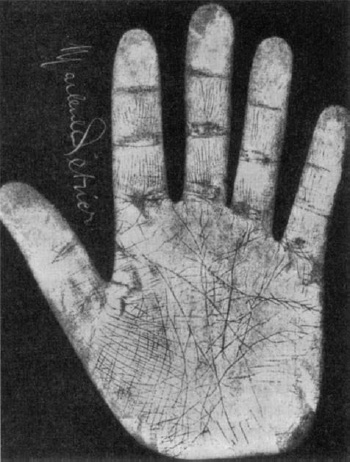

Marlene Dietrich

THE

STREETS

OF BERLIN

M arlene Dietrich would never forget the sounds of Schneberg, Berlin, where she was born on December 27, 1901: soldiers marching in step, horses clip-clopping along, and trains whooshing by. Sedanstrasse, where she spent the first few years of her life, is situated on the so-called island, set off from the rest of the city by train tracks. The military had built barracks on the island, and since the time of the Franco-Prussian War, the railway was used to transport soldiers and weapons. Sedanstrasse was a treeless part of Berlin, where the military dominated the lives of the civilian population. Marlenes father, Louis Erich Otto Dietrich, was a police lieutenant, his precinct located on the ground floor of the building where he lived with his family.

The Dietrichs were Calvinists who had been driven out of the Palatinate and settled in Brandenburg under the protection of Frederick the Great. Marlenes sister Elisabeth insisted, however, that they were actually Huguenots, who lived by the virtues of frugality, Even so, he felt like an officer. He was elegant, generous, and popular, and he enjoyed being seen in the company of lovely ladies and living above his means. In the few photos of Dietrich that have been preserved, his penchant for posturing is striking: his proud, upright stance emphasized his lieutenants waist, and his mustache twirled upward. Born in 1867, he was one of the Wilhelminians whose immediate ancestors had achieved it all, uniting the country and defeating the French, but the men of his generation had no prospect of earning fame on their own.

Louis did not remain in the military for long. In his early twenties, he switched over to police work, a career that offered the potential of achieving esteem, security, and status, although little in the way of advancement or pay. Berlin was divided up into individual precincts, and the official in charge of a given precinct had to live there. The policeman was subject to a higher order. Even after hours, he had to remain in uniform; access to taverns was restricted; and membership in clubs was permitted only with the consent of his superior. The policeman was an outsider, always on duty. The only attractive part of the job was the prestige. Louis lived beyond his means to conceal his material indigence. Marlenes father did not tone down his brusque air of authority even within his family, where he was intent on displaying his strength, issuing orders, demanding obedience, and preserving his own power. It was abundantly evident in his appearance as well, notably in his wedding photo, taken in 1898, which displays his enduring love of uniforms and posing for the camera. The woman at his side looks tacked on, three of her fingers peeking eerily out of the crook of his left arm. He is paying no attention to her. Bare-headed and clad in his Sunday uniform, he stares straight ahead, while his bride, twenty-two-year-old Wilhelmina Elisabeth Josefine Felsing (who went by Josefine), peers at him timidly.

Like so many Berliners, the Felsings had moved there from elsewhere, in this case from Giessen. They had been clockmakers for generations. The shop they opened in 1820 was one of the best known businesses in old Berlin. The Felsings specialized in elegant clocks and proudly called themselves Purveyors to Their Majesties the Emperor and Empress. In 1895, Josefines father Albert Felsing donated a golden clock to the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church. The family had a stylish residence in a building annex of Unter den Linden 20, which they owned. They were proud of their proximity to the royal castle and were not pleased to see their daughter marry a police lieutenant, which meant a drop in Josefines social status. But Josefine was drawn in by Louis Dietrichs stylish appearance and fine-sounding words.

Louis and Josefines first child, Elisabeth Ottilie, was born two years after the wedding, and their second, Marie Magdalene, followed in 1901. Josefine, now twenty-five years old, no longer saw her husband as much of a hero and went to great lengths to bring up the two girls in accordance with her ideals. She ran a tight ship in her household. Marie Magdalene smarted under this matriarchal rule. She and her sister differed in many ways: Elisabeth was the ugly duckling, shy and nervous, and Marie Magdalene the pretty child who was proud of her long hair. Elisabeth claimed that men went crazy for her sister when Marie Magdalene was only ten years old.

The everyday monotony in the police household was punctuated by several moves: in 1904, to nearby Kolonnenstrasse, and two years later to bustling Potsdamer Strasse. Elisabeth Ottilie wrote that she and her sister were afraid of these passages. The girls must have sensed their mothers anxiety about further social decline. Louiss superiors gave him the poorest evaluations, and the change of apartment from the upper floor to the mezzanine took on a symbolic significance. Then Louis fell ill. Once, my mother moved us to where my father was. She would walk us by the hospital, so my father could look down from his barred window and see us, Marie Magdalene would recall later. On August 5, 1908, Police Lieutenant Louis Erich Otto Dietrich succumbed to his nervous disorder (which was likely syphilitic in origin) at the age of forty-one. The disgrace of the familys comedown was now compounded by the disgrace of this death. Josefine kept the cause of death from her children, no doubt fearing that their fathers illness could have been transmitted to them.

Next page