For Lily

Its just like I always said, that John Wayne, an actor, was more important to the mass psyche than any single American president. His longevity, his penetrationall of that ultimately has affected how human beings behave, what choices they make, who they think they are, more than any straight pragmatic political action and groupthink.

Jack Nicholson, Vanity Fair, August 1986

Contents

If Id known that, I would have put that patch on thirty-five years earlier.

John Wayne

On April 7, 1970, the night of the forty-second presentation of the Academy Awards, Hollywoods annual celebration of industrial-strength narcissism, films elite gathered at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in downtown Los Angeles to honor the pictures, actors, directors, cinematographers, screenwriters, and other skilled artists and technicians that were chosen by the Academys voting members as the best of the previous year.

John Wayne, nominated for his performance in Henry Hathaways True Grit, faced strong competition: Richard Burton in Charles Jarrotts Anne of the Thousand Days, a star vehicle for the hugely popular Burton and the odds-on favorite in Vegas; Dustin Hoffman for his scarily brilliant work in John Schlesingers blistering Midnight Cowboy; Jon Voight in the same film for his poignant depiction of innocence corrupted; and the magnificent Peter OToole sorrowfully wasted in the cringe-worthy, no-chance musical version of Goodbye Mr. Chips, directed by Herbert Ross.

Three significant events took place that evening. The first was the official acceptance of late-bloomer Jack Nicholson into the Hollywood mainstream, who would go on to dominate it for the rest of the twentieth century and into the first decade of the twenty-first. He was nominated in the category of Best Performance by an Actor in a Supporting Role, for his portrayal of the sympathetic, charming, and exceedingly vulnerable Hanson, a relatively small role that not only yielded an utterly unforgettable performance but signaled a cultural shift in American movies image of who and what a hero was.

The second was the awarding of a noncompetition, honorary Academy Award to Cary Grant, one of the giants of the industrys golden age. Grants film career began in 1932 and lasted until 1966, when, still at the top of his game, he wisely chose to retire from the industry and go out on top. Now, four years later, he was finally being recognized for his remarkable accomplishment in helping to establish the iconic image of the romantic Hollywood leading man. It was hard to believe that Grant, who had appeared in so many films for many of Hollywoods greatest directors (some greater than others, but most arguably made their best films with him), among them Alfred Hitchcock, George Cukor, Howard Hawks, Frank Capra, Leo McCarey, Stanley Donen, and Michael Curtiz, had never been officially acknowledged by his peers with a competitive Oscar. Grant, who was considered a troublemaker by the major studios because of his insistence on going freelance in an age of contract players, the first to do so and the first to pay for his freedom by being refused a real Oscar, was reduced to tears when, late in life, he finally received his honorary statuette.

The third, and perhaps most fascinating, was the competitive Best Performance by an Actor Oscar that John Wayne won for his self-parodic performance as Rooster Cogburn. Of the 164 movies he made in his long and brilliant career, including the twenty-four he did with John Ford, True Grit is perhaps the least Oscar-worthy in terms of pure cinema. However, for his long-overdue recognition17 of the films he appeared in were among the 100 highest-grossing films of all time, collectively grossing more than $400,000,000 (in twentieth-century dollars), and since 1951 he had consistently placed among the top ten box-office starsthis was the one Hollywood chose to acknowledge Waynes great contribution to American movies.

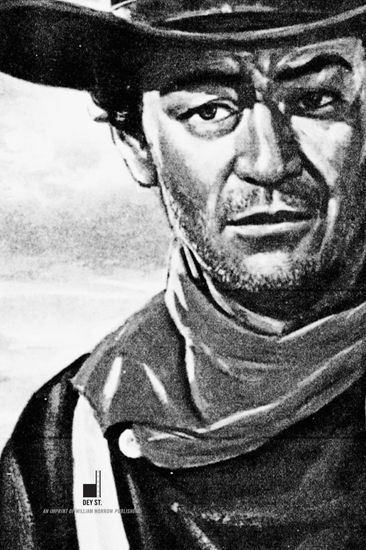

His astonishing body of work, those 164 movies over a fifty-year span, where he upheld not just the law of the land but the American way, defined him as Hollywoods definitive Indian-fighting (and later on Indian-defending), two-fisted, six-gunned, wagon-trained, swinging-bar-doored, maiden-preserving, democracy-defending all-American hero, the most enduring on-screen symbol of the vanishing prairie. And, although he was never in the military, he fought Americas enemies in World War II with patriotic propaganda films that came complete with recruiting stations set up in theater lobbies. He was an avowed enemy of Communism and especially American Communists. At the height of his career, he set about to rid Hollywood of both and did a fairly effective job. However, by age sixty-three, with the wear, the tear, the weariness on his craggy face, with cobra eyes that looked almost Asian, and the sagging body of a Hollywood life ridden hard and put away wet, he was considered pass by Hollywoods young 70s honchos, some not yet even born when Wayne made some of his best movies.

He had been nominated twice before, once as an actor in 1949 for Best Actor in Allan Dwans no-frills war movie Sands of Iwo Jima, when he lost to Broderick Crawford in Robert Rossens neopolitical All the Kings Men (a role Wayne turned down because he disliked the films political message), and once as producer (Best Picture/Batjac, his own production company) in 1960, for his post-Disney adult version of the classic story of The Alamo, which he also directed. Wayne lost that time to producer/director Billy Wilder for The Apartment .

Why was Wayne perennially passed over? For one thing, he made enemies in the industry where many never forgave him for his politics, and because of it, some of his greatest performances, like Ethan Edwards in John Fords The Searchers, were famously ignored by the voters of the Academy . Made during the height of the blacklist, The Searchers provides not just the best performance in any Hollywood film of 1956, but one of the greatest performances in any film anytime, anyplace, anywhere. Five years earlier, Stanley Kramers monumental High Noon, a western written and coproduced by blacklisted Carl Foreman, was nominated for eight Oscars and won four, including Best Actor for Waynes friendly rival for most of their careers, Gary Cooper. Why? Perhaps part of the reason is that Wayne was the former president of the radical-right Motion Picture Alliance, begun by Walt Disney, Sam Wood, and others in the early 40s, the tea-party-style posse of a politically divided Hollywood that helped ruin the careers of some of its best talent (and biggest moneymakers), including Foreman. In 1971, an unrepentant Wayne told Playboy magazine, Ill never regret having helped run Foreman out of this country. It was not hard to tell which side the Academy was on.

But it wasnt only politics. As larger than life as he was for audiences, to the Hollywood studios that employed him and the voting Academy members, Wayne was, almost to the end of his career, considered a glorified B movie actor, his films never considered quality or art, certainly not worthy of Oscar. The studio book on Wayne was that he was just another Hollywood cowboy, that he didnt have the emotional range of a Jimmy Stewart, the gritty elegance of a Spencer Tracy, the spitting toughness of a Humphrey Bogart, the street smarts of a Jimmy Cagney, the beautiful pain of a Marlon Brando, the urban cynicism of a William Holden, or the inherent populism of a Henry Fonda, all Oscar winners. He was just there, Hollywoods unanointed Duke, as dependable as oats. Yet, as film critic and historian Andrew Sarris, promulgator of American auteurism, rightly acknowledged on the occasion of Waynes True Grit nomination, his forty years of movie acting and thirty years of damn good movie acting... Waynes performances for John Ford alone are worth all the Oscars passed out to the likes of George Arliss, Warner Baxter, Lionel Barrymore, Paul Lukas, Broderick Crawford, Jose Ferrer, Ernest Borgnine, Yul Brynner and David Niven... ironically, Wayne has become a legend by not being legendary.