Contents

In the Territory

19131931

There is no ancestor so powerful as ones earlier selves.

LEWIS MUMFORD (1929)

D ecades after the blazing hot afternoon in June 1933 when Ralph Ellison, on his first and last outing as a hobo, climbed fearfully and yet eagerly aboard a smoky freight train leaving Oklahoma City on a dangerous journey that he hoped would take him to college in Tuskegee, Alabama, his memories of growing up in Oklahoma continued both to haunt and to inspire him. For a long time he had suppressed those memories; then the time came when he began to crave them.

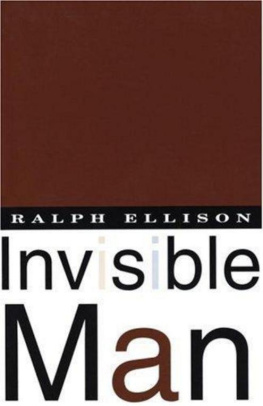

The turning point had been his triumph in 1952 with his novel Invisible Man. That success had led to a cascading flow of honors such as no other African-American writer had ever enjoyed. In 1953, he won the National Book Award, besting The Old Man and the Sea, by Ernest Hemingway, one of his idols. Later, the American Academy of Arts and Letters elected him a member, one of the fifty distinguished American men and women who formed its inner core. At the White House, first Lyndon B. Johnson and then Ronald Reagan awarded him presidential medals. At the behest of the novelist and critic Andr Malraux, another of his idols, France made him a Chevalier de lOrdre des Arts et des Lettres. The most venerable social club in America connected to the arts, the Century, in New York, elected him as its first black member. Harvard University, awarding him an honorary degree, offered him a professorship. Never out of print and translated into more than twenty languages, Invisible Man maintains its reputation as one of the jewels of twentieth-century American fiction.

Ellisons triumph in 1952 had also led to a tangled mess of fears and doubts about his ability to finish a second novel at least as fine as Invisible Man. By the time of his death in 1994, his failure to produce that second novel had made Ellison, a proud man, the butt of surreptitious jokes and cruel remarks. The snickering and giggling behind his back often left him prickly and tart, if not downright hostile. Clinging fearlessly and stubbornly to the ideal of harmonious racial integration in America, he found it hard to negotiate the treacherous currents of American life in the volatile 1960s and 1970s. Although he always saw himself as above all an artist, and published a dazzling book of cultural commentary in 1964, his later successes were relatively modest. For some of his critics, his life was finally a cautionary tale to be told against the dangers of elitism and alienation, and especially alienation from other blacks. For his admirers, however, no one who had written Invisible Man and so skillfully explicated the matter of race and American culture in his essays could ever be accounted a failure. To some peopleyounger black writers mainlywho hoped and perhaps even expected him to help them, he frequently seemed cold and stingy. To otherswhites especiallyhe was a man of grace, intelligence, wit, and courage who saw his nation with prophetic optimism and clarity.

Each of these conflicting views had, at the very least, an element of truthand the roots of these conflicts may be traced, not surprisingly, to his upbringing in Oklahoma. Seeking artistic inspiration as the decades passed, he turned more and more to memories of his youth in what once had been the old Indian and Oklahoma territories. From this virgin landas both whites and blacks saw itthe state of Oklahoma had been carved in 1907. Certainly he had no interest in living as a mature man in Oklahoma. It was more than enough for him to brood on the past, and to come back every seven years or so to visit the old neighborhoods, talk with old friends, bask in the glow of his celebrity, and revive his creativity at its ancestral source. On these visits, he looked sorrowfully on the banal evidence of progress and urban renewal that marred the city, and even more sadly on the spectral presence of those old friends now dead and gone. When I get there Im like a ghost, he declared once, or a Rip Van Winkle who has slept for twenty years and awoke to discover that his world has changedbut how!An obsessive refrain sounds in my mind: Where have they all gone? Where, oh where?

Fascinated by the power of myth and legend, and alert to the ways in which geography often means fate, he saw Oklahoma as embodying some of the more mysterious forces in American culture. He believed that the region possessed or had possessed almost every element concerning power, race, and art that is essential to understanding the nation. It had Indians, whites, and blacks; treaties solemnly made and shamelessly broken; despair and hope, failure and shining success. Here was the legacy of the dispossession of the Five Civilized TribesCherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminolefrom their homelands in the South and their expulsion in the 1820s and 1830s, by way of the Trail of Tears, to Indian Territory. (Ralph cherished the fact that he was a wee bit Creek! on his mothers side, just as he was also proud of the white ancestry on both sides of his family and the black ancestry that was predominant in his physical features.) In 1879, whites had entered Indian Territory for the first time, with the avowed aim of seizing much of the land. Divided and united by history, Oklahoma was culturally the Wild West, the Southwest, and the Old South; it was ancient but also brazenly new. One day, Oklahoma City did not exist. The next day, April 22, 1889, after settlers had raced to stake their claims as part of the official Great Land Run, its population stood at ten thousand. The Oklahoma Territory was born. Ironically, helping to keep in line any indignant Indians were the famous black Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry.

Ralph, born only six years after Oklahoma became a state, could put human facesblack, white, Indian, and mixedon this past. For the freed slaves and their children and for free blacks in general, Indian Territory had meant at first an almost providential deliverance from Jim Crow. Many blacks rushed to claim the one-hundred-acre parcels of land allotted by the government to new settlers, so that by 1900 almost sixty thousand blacks lived in the Indian and Oklahoma territories. Many of them saw Oklahoma the way Mormons had seen the new territory that became Utah. Twenty-eight all-black towns sprang up. Edward P. McCabe, a passionate spokesman for black migration and the establishment of a black state, implored his fellow African-Americans to make history: What will you be if you stay in the South? Slaves liable to be killed at any time, and never treated right; but if you come to Oklahoma you have equal chances with the white man, free and independent.

This was the promise that in 1910 lured a young, newly wed couple, Lewis and Ida Ellison, to Oklahoma City. Their first child, Alfred, died as an infant. Their second, Ralph Waldo Ellison, was born at 407 East First Street, in Oklahoma City, on March 1, 1913. For most of his life Ralph would offer 1914 as the correct year. Presented with a chance to do so, around 1940and despite the fact that he was on the whole fastidiously honestRalph decided to shave a year from the record. The U.S. Census taker got it right in January 1920 when he listed Ralph Ellison as being six years old, born in 1913. A note in his mothers hand, written behind a photograph of Ralph as a toddler, sets his time and date of birth as 1:30 a.m. on Saturday, March 1, 1914. But March 1 fell on a Saturday in

Next page