POSTSCRIPT

EXPOS

Modin, in his seventies in the early 1990s, was suddenly a pauper. With the massive devaluation of the rouble after the collapse of communism, Russian pensions were decimated. Key retired KGB agents such as him found themselves suffering in harsh economic circumstances.The new KGB regime in Moscow decided to let Western journalists into Russia to interview former master-spies, such as Modin, who would command American dollar fees to make up in part for their diminished pension incomes.This was to be organised by the new wave of KGB spies, who believed they were aping Western capitalism by demanding commissions for the interviews. Having lived in England during twelve years of the hottest period of the Cold War, from 1973 to 1985, I was intrigued (as many journalists were) to discover who was the Fifth Man in the Cambridge Ring, and investigate other espionage agents. In 1993, I arranged to interview Modin in Moscow. Face-to-face interviews took place in Modins Moscow apartment on a daily basis over two weeks. I later wrote The Fifth Man, based on those and other interviews with KGB agents (it was published by Sidgwick & Jackson and Pan Macmillan in 1995). In 1996, I began researching a further member of the Cambridge Ring, American Michael Whitney Straight, who had been recruited by Blunt. In the same year, I returned to Russia with British documentary filmmaker Jack Grossman; Modin agreed to the on-camera interviews for a $US1000 cash fee for his appearances in ten hours of filming over two days. Jack Grossman and I stayed at a hotel in Moscows west and took a taxi a few kilometres to the KGB mans flat in an unprepossessing block. Modin was now a heavy-set man with a thick wave of white hair and a beard.

Hes the spitting image of Colonel Sanders, Grossman whispered to me as he set up his camera.

Modin had by this time published his autobiography, Mes camarades de Cambridge, brought out by French publisher Laffont in 1994, after decades of advising his double agents to write their own stories. His decision to commit pen to paper himself was another way of earning quick money from eager Western publishers in France, England and the United States. Its revelations would also keep Western investigators wandering aimlessly in an espionage labyrinth.

I asked the Russian about the special missions for George VI that Blunt had made from 1945 to 1947. Modin knew Blunts assignment had been made public by British historian Hugh Trevor Roper (Lord Dacre) and elaborated on by a few journalists. But no-one had delved deeply into the reasons for the trips and what was recovered by Blunt for the archives at Windsor Castle.

What was the correspondence about? I asked.

Royal matters, Modin replied in his resonant, sometimes sing-song Russian accent, some of them private.

Did they include correspondence between the Duke of Windsor and Hitler?

Oh, yes, of course. Much from him to the Nazis.

Can I see any of them?

That would be impossible.They are classified not for Western eyes. Modin paused. I wish to tell you that I shall not give you any more information than Western intelligence already knows.

You are assuming I am linked to a Western agency?

I must.

It doesnt happen to be true but I understand your position, I said. Anyway, it still puts me well ahead of the Western media pack.

I probed about the Hitler correspondence. Modin kept blocking and avoiding the questions.

You know, there is another line of investigation [for you] here, Modin told me after fifteen minutes of getting nowhere. There are much more interesting royal letters that were passed to us by Blunt.

Can you tell me about any of them?

Modin frowned and seemed to be thinking deeply.

I can tell you about one that Blunt showed us to demonstrate his importance as a palace man.

As the kings art curator?

Yes, art curator.

Please... I said, glancing at Grossman.

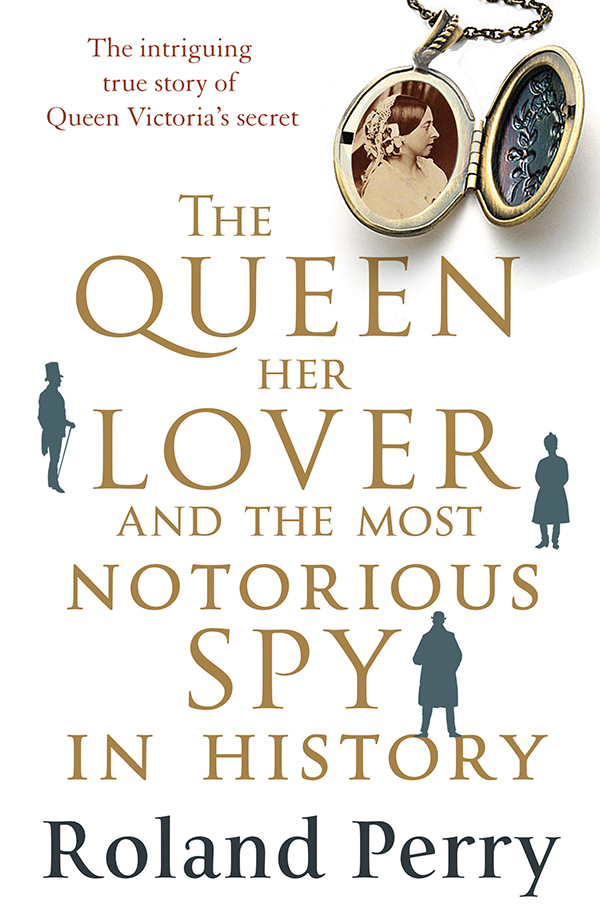

The letter was written by Queen Victoria to her daughter. She confesses she had an affair before she was queen.

I waited.

Thats all I can recall, Modin said. I read some of the letters, but there were thousands.

So you could have blackmailed the royals?

Yes.

Did you ever try?

No, Modin said with a vigorous shake of the head, we would not do it.

With Grossman filming, I saw several other ex-KGB agents, including Vladimir Barkovsky, who had made a study of Blunts material at KGB headquarters. Modin helped arrange the meeting and Barkovsky came to the Moscow Hotel at which we were staying. I waited for the Russian in the lobby. After a half-hour wait mid-morning in early October 1996, I noticed a lean, short older man in dark glasses. He wore a beige trench-coat and was carrying a black briefcase. I thought, This is the only person in the lobby who looks like a spy. I approached the man and found it was indeed Barkovsky.

He was not as relaxed or polite as Modin but he was cooperative, explaining he needed the $US500 that he would be given for the half-hour interview to pay for a medical operation on his grandson.

Our health system is not what it was, he complained.I have to go private now and it costs.

I asked him about the VictoriaVicky correspondence.

Yuri tells me you are interested in Victorias letters to her daughter in 1860, Barkovsky said reaching into his briefcase. I have copies of a sample of these letters. But I cant let you read them.

Barkovsky shuffled photocopies of about ten letters, before he looked up and said: I am able to disclose a little information from one dated 25 July 1860 in which Victoria made a point of confessing a relationship before she met Albert. It concerned a member of the House of Lords who was in her royal court.

Does she say which lord?

I am not at liberty to divulge that.

But he was a member of her court?

Two courts, two monarchs.

Who was the other monarch?

That is for you to find out.

Are there more references to the affair...?

Barkovsky waved a letter from Victoria at Holyrood Castle, dated 7 August 1860.

When was the letter written?

Barkovsky looked at the letter.

August seventh, 1860.

Is it possible to film any of these copies? Grossman asked.

No, I am sorry. If you discover the name of this lord, please do not divulge that I gave you this information.We have a rule of not disclosing the exact nature of espionage material. We have always paraphrased such material for the intended recipient. In this case, the letters are strictly banned. I am trusting in you because of your connection to Yuri Ivanovitch [Modin], who has found you most reliable.

I finished the book on Straight, Last of the Cold War Spies, which was published by Da Capoafter lengthy correspondence with Straight himselfin 2005. Five years later I began an investigation into the veracity of the information in the VictoriaVicky letters and discovered strong evidence of a relationship between Victoria and the thirteenth Lord Elphinstone. I then examined the Elphinstone archive at the British Library. It ran to 309 files. Library officials estimated that it would take six years intense work to devour them all. I spent several months in 2011 and 2012 cherry-picking relevant files, and discussed them with Grossman, telling him that I had established that Elphinstone and Victoria had had an affair before she became queen. I saw it as a cold case, like the television series.

A cold case, yes, Grossman agreed. Except you do not go back to a murder and a dead body. Its a state secret so its probably well buried. Perhaps the best kept one in the history of the royals.

Next page