FURIOUS

IMPROVISATION

How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands

Made High Art out of Desperate Times

Susan Quinn

A Mind of Her Own:The Life of Karen Horney

Marie Curie: A Life

Human Trials: Scientists, Investors, and Patients in the Quest for a Cure

To DHJ

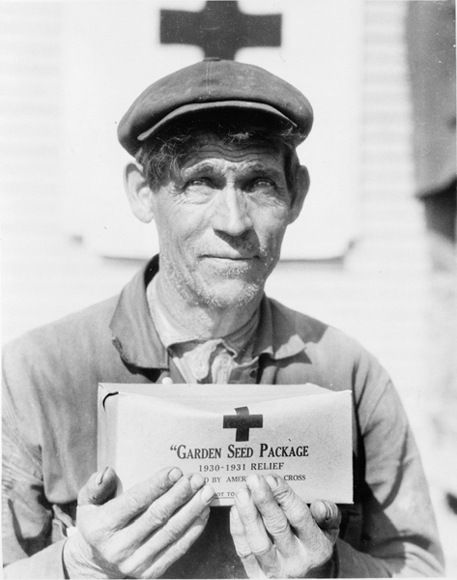

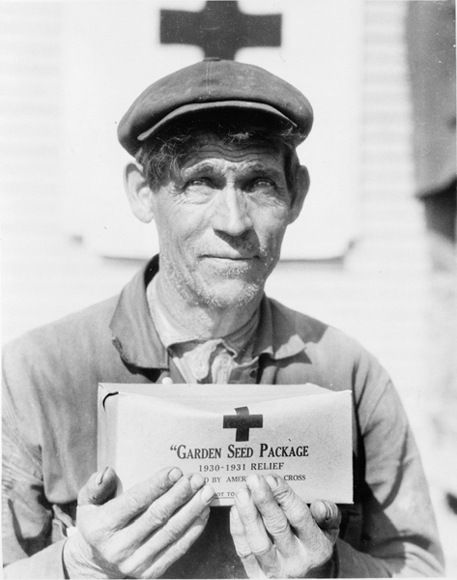

One day in January 1931, a white tenant farmer named H. C. Coney who lived near the little town of England, Arkansas, reached the limit of his patience. He and his wife and children struggled in the best of times, in a cabin with newspaper on the walls and a wood stove for heat. But the drought of 1930, coinciding with the greatest depression in the nations history, had devastated the farms of the South. Without a harvest of corn or cotton, the situation had grown desperate. Coney couldnt even find anyone to buy his truck for the deflated price of $25, and there werent enough clothes among all the family members, as he later told a reporter, to wad a shotgun proper. The stingy ration of lard, flour, and beans, given out to drought victims by the Red Cross, kept the family constantly on the edge of starvation. Then, on January 3, 1931, a neighbor lady told Coney that her children hadnt eaten in two days. That sent him into action.

Coney and his wife jumped into his truck and drove to the nearby home of a landowner named L. L. Bell, the local chairman of the Red Cross. There Coney found a crowd of hungry neighbors, all demanding food. The chairman refused aid because the office had run out of forms and couldnt proceed without them. (Red Cross officials worried about impostors hoarding supplies.) Coney yelled to some of the crowd to jump on his truck and drive to the nearby town of England, where the stores were, to demand food and, if necessary, to take it. By the time they reached England, a crowd of some five hundred white and black farmers had gathered, shouting, Were not going to let our children starve, and, We want food and we want it now.

The Lonoke County drought chairman, a prominent lawyer and plantation owner named G. E. Morris, stood up before the crowd and promised that he would get them food if they would just be patient. Morris made frantic phone calls to Red Cross authorities in Little Rock, which finally resulted in the distribution of $2.75 worth of rations, meant to last for two weeks, for each of five hundred families in need. It wouldnt have taken much to provoke a violent showdown, Coney said afterward, but they doled out the feed and we all idled back here without nobody gettin hurt. Thus ended the England riot.

Arkansas farmer with seed package, 193031 (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

Reactions to the January 3 incident in England, Arkansas, varied wildly. The New York Times called it an invasion of armed and hungry farmers and their wives. The Red Cross spokesman minimized the incident, insisting that the trouble was incited by about 40 men from one section of the county, causing only temporary excitement but no damage to property or persons.

Communists had nothing to do with the desperate actions of the hungry farmers in England, Arkansas. But the discontent of farmers in the South, and the impotence of the federal government in the face of it, created opportunities for Communist organizers. Not long after the England event, the Communist Party distributed leaflets in the drought area charging that the Red Cross, headed by Hoover, is deliberately starving toiling people to death. In March, a young party member named Whittaker Chambers used the event as the basis for a short story in the leftist monthly New Masses called Can You Make Out Their Voices? And that story, in turn, became the basis of a play written and staged by the fiery and energetic director of experimental theatre at Vassar College, a woman named Hallie Flanagan. Flanagan, along with co-writer Margaret Clifford, called their play Can You Hear Their Voices? and turned it into a less preachy and more powerful evocation of the desperate plight of farmers.

The main character of their play, Ed Wardell, is a self-professed Communist, and some of his neighbors resist him as a troublemaker. But as their cows die and their families grow hungrier, many come around to his point of view. The climactic moment comes when a young mother, unable to find milk for her baby, smothers it in a blanket rather than see it tortured to death by inches. When they can stand it no longer, Wardell and his supporters sweep into town in their flivvers and stop in the middle of the street. The men with their guns and the women with their babies storm the Red Cross relief office, the stores, and the landowners barn for food and milk.

To increase the impact of the play on their middle-class Vassar audience, Flanagan and Clifford introduced a parallel story, involving a very rich congressman named Bageheot and his daughter, Harriet, who is about to come out at a debutante party costing $250,000. Harriet Bageheot is a social butterfly, but not without some awareness of what is going on in the world. She finds her parents plans for her coming-out party excessive. Look here, Father, she says at breakfast, doesnt it seem a little incongruous to be giving parties with the country in the state it is? With people standing in bread lines and dying of hunger?

Her fathers reply is that it would be selfish not to spend. The thing to do is to keep money in circulation.

In her final scene, at the debutante ball, Harriet rises drunkenly to speak. The crowd, thinking shes going to announce her engagement, shouts out, Whos the lucky man?

No, theres nothing tender about this, she says. I want to tell you something important. I want to tell you about the drought.

The crowd responds, Hurrah! The drought! Is there a drought?

Theres a drought, Harriet insists. In the United StatesIn the South. Its a terrible thingIts killing the cropsIts making people hungryIts making people thirstyAnd you know what it is to be thirsty, my children.

There are cries of Give the girl a drink! and Lets all have a drink!

But Harriet continues, Were the educated classes. Were the strength of the nation! Whatre we going to do about it? Whatre we going to do about the drought?

Harriets friends say nothing. Finally, the orchestra ends the awkward silence, striking up the tune Just a Gigolo.

The final scene takes place in the drought-stricken South. Ed Wardell and his wife, fearing retribution from government troops for the attack on the food supply, send their two young sons away to keep them from trouble. Try to remember all youve seen here, Ed Wardell tells his sons. Remember that every man ought to have a right to work and eat. Every man ought to have a right to think things out for himself.

The lights fade out, and a final message appears on a screen: These boys are symbols of thousands of our people who are turning somewhere for leaders. Will it be to the educated minority? CAN YOU HEAR THEIR VOICES?

The Vassar production of Can You Hear Their Voices? in May 1931 came just a few months after a historic debate in Washington about how to deal with the growing desperation of people on farms and in cities throughout the country. On one side were President Herbert Hoover and his allies, who insisted that private charity could handle the problem. Hoover looked to the past for reinforcement, quoting President Grover Clevelands dictum that though the people support the government, the government should not support the people. Government loans, which promoted self-help, were all right, but direct aid to hungry people was dangerous. The dole, Hoover insisted darkly, would lead to an abyss of reliance in future upon government charity.

![Viola Spolin - Improvisation for the Theater: A Handbook of Teaching and Directing Techniques [1963 ed.]](/uploads/posts/book/406435/thumbs/viola-spolin-improvisation-for-the-theater-a.jpg)