IN MEMORY OF MY HUSBAND,

PHILIP STERLING (19071989)

AND MY SISTER,

ALICE LAKE (19161990)

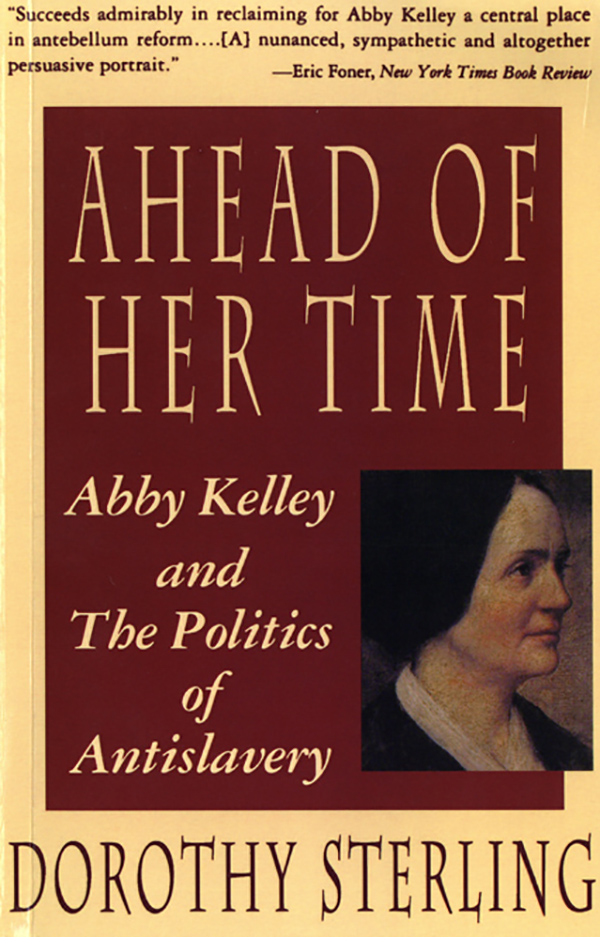

During the eight years that I have worked on this book, I have incurred debts to scores of librarians and archivists. The bulk of the Abby Kelley Foster Papers are located at the American Antiquarian Society, where I would especially like to thank Nancy Burkett, Georgia Barnhill, Dianne Pugh, Joyce Ann Tracy, and Sidney E. Berger, and at the Worcester Historical Museum, where Mark Savolis and Norma Feingold generously assisted me. (I have a mental picture of Norma Feingold precariously balanced on the museums stairs, in order to take a snapshot of the Abby Kelley portrait that appears on the cover.)

Sampling the riches of the Anti-Slavery Collection at the Boston Public Library has always been made pleasant by the kindness of Roberta Zonghi and her staff. I am also grateful to Eva Moseley, curator of manuscripts at the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women; Rodney Dennis, curator of manuscripts at the Houghton Library, Harvard University; Susan L. Boone, curator of the Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Library; Linda Seidman, Archives and Manuscripts, University of Massachusetts; Roland Baumann, archivist, Oberlin College Archives; Nancy Dean of the Cornell University Library; Carolyn A. Davis, George Arents Research Library, Syracuse University; Rosalind Wiggins, archivist for the New England Yearly Meeting of Friends, and her colleagues at the Rhode Island Historical Society, where the Friends papers are housed. I have written so often to Karl Kabelac of the University of Rochester Library and to Phil Lapsansky of the Library Company of Philadelphia that we are on firstname terms, and I consider them my friends. Thanks should also go to librarians at the Rare Books and Manuscript Library, Columbia University; the New-York Historical Society; Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; Ohio Historical Society; Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress; William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan; Quaker Collection, Haverford College Library; Kent State University Library; Massachusetts Historical Society; Douglass Library, Rutgers University.

As always, I am deeply indebted to the Wellfleet Public Library, particularly to its director, Elaine Mcllroy, and to Claire Beswick, in charge of interlibrary loans. I could not have completed this book without the books and microfilm that she borrowed from institutions across the country. And the microfilm and dissertations that she was unable to obtain, my children, Peter Sterling and Anne F. Sterling, borrowed from their university libraries. Professor Jacqueline Jones of Wellesley College and my good friend Rosemarie Redlich Scherman also lent me hard-to-find material.

Ann Gordon and Patricia Holland, editors of the papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, were extraordinarily generous, not only sending me copies of relevant letters from Stanton and Anthony but introducing me to other researchers in the field. Through them I have corresponded with Judy Wellman of SUNY, Oswego, who is completing a book on the Seneca Falls womans rights convention and who identified several of Abby Kelleys acquaintances in upstate New York, and Elizabeth C. Stevens, who is completing a dissertation on Elizabeth Buffum Chace. Elizabeth Stevens and I have exchanged information so frequently that we, too, have become friends. She was good enough to lend me her precious 1914 biography of Chace so that I could have some of the illustrations copied.

Dorothy Porter Wesley, curator emeritus of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, has been supplying me with information and encouragement for more than three decades. Her knowledge of black and womens history is unsurpassed; her generosity in sharing it sets an example for all researchers. Margaret Hope Bacon, biographer of Lucretia Mott as well as Abby Kelley, suggested avenues of research and sent copies of Mott letters that I might not have known of otherwise. Dr. Elizabeth Kirk of Brown University spent precious hours identifying the Shakespeare quotations that decorated the walls of an 1882 Suffrage Subscription Festival.

When I first met Dr. Jean Yellin of Pace University some twenty years ago, we discovered a mutual love for the antislavery women and have been pooling information ever since. She was particularly helpful in pointing out Elizabeth Margaret Chandlers Mental Metempsychosis as background for a puzzling Abby Kelley letter and in identifying the people in the daguerreotype of an antislavery meeting that appears opposite page 117.

My acquaintance by correspondence with Richard J. Wolfe, curator of rare books and manuscripts, Boston Medical Library, also goes back many years. I am particularly grateful for his photocopies from nineteenth-century medical texts that helped me define the illnesses of Abby Kelley and her family and identify her physicians. Dr. Stanley Robbins of Harvard Medical School, Dr. Nelson Fausto of Brown University Medical School, and my daughter, Anne, also of Brown, shed additional light on Kelley-Foster health problems.

Frank E. Fuller, historian of the Moses Brown School, Providence, Rhode Island, which Abby Kelley attended in 1826, was unusually generous in lending me old books, catalogs, and pictures of the school and answering innumerable queries. Dr. Sidney Kaplan, University of Massachusetts, introduced me to the papers of Dr. Erasmus Hudson and located a picture of Hudson for me. Ellen C. DuBois, of SUNY Buffalo, sent me a wonderful letter from Lucy Stone to Abby Kelley, and Lorraine Jackson painstakingly copied the reports of the 1851 Womans Rights Convention from the New York Tribune and Herald. Frank Clarkson, who lived in the Kelley-Foster farmhouse in Worcester as a boy, shared his recollections and gave me an early photograph of the farm. Carolyn B. Casper, my college classmate, deciphered some Lucy Stone letters that were impossible to read on microfilm. I enjoyed comparing notes on many Frederick Douglass-Abby Kelley interchanges with William S. McFeely of the University of Georgia and Wellfleet, Massachusetts, when he was completing his biography Frederick, Douglass. Rhoda Jenkins of Greenwich, Connecticut, generously sent me copies of pictures of her great-grandmother Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Jean Stearns of Wellfleet, Massachusetts, helped locate references to the 1787 Constitutional Convention. For all these kindnesses, many thanks.

Linda E. McCausland of Orleans, Massachusetts, did a loving job of copying old photographs and illustrations from nineteenth-century publications. Joan Willis and Ellen Anthony of Wellfleet, Massachusetts, strug-gled with my execrable handwriting until they had turned out neatly organized Notes and bibliography.

For forty years Philip Sterling read the manuscripts of every book I wrote, giving them the benefit of his thoughtful appraisal and skilled editing. He read part of the Abby Kelley biographyI smile when I come across some of his incisive turns of phrasebut he did not live to finish the job. After his death old friends came forward to fill the gap. The book has benefited from the thoughtful reading it received from Milton Meltzer, Richard Stiller, Paula Vogel, Hilda and Herbert Lass, as well as from my friend and editor, James L. Mairs.

Writers often say that their lives are lonely. Mine has been lonely this past year, but as I read over these acknowledgments, I realize how much sustenance as well as information I have received from historians, librarians, and fellow writers who never hesitated to take time from their own work to send me friendly and encouraging as well as informative letters. Going to the post office for the mail is the pleasantest chore of my day. To this network of correspondents I want to express again my gratitude.

Next page