NOTE ON

QUOTATIONS

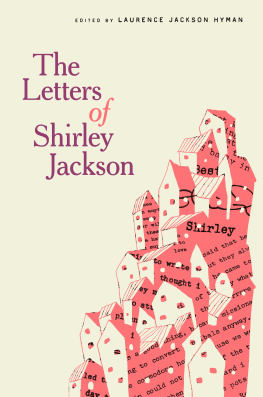

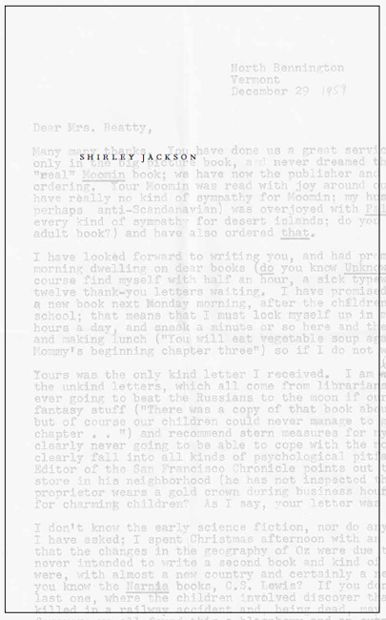

I N HER LETTERS AND ROUGH DRAFTS, SHIRLEY JACKSON USUALLY typed using only lowercase letters. I have chosen to preserve her style as a way of delineating unpublished material.

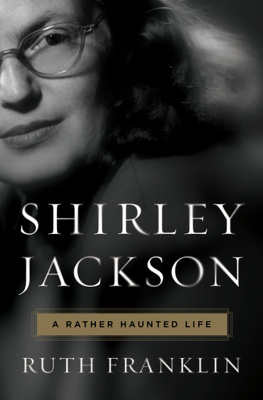

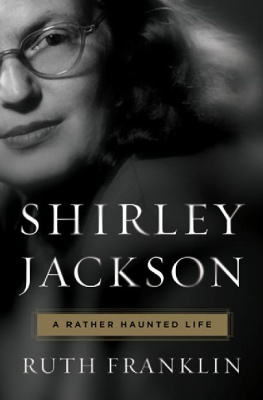

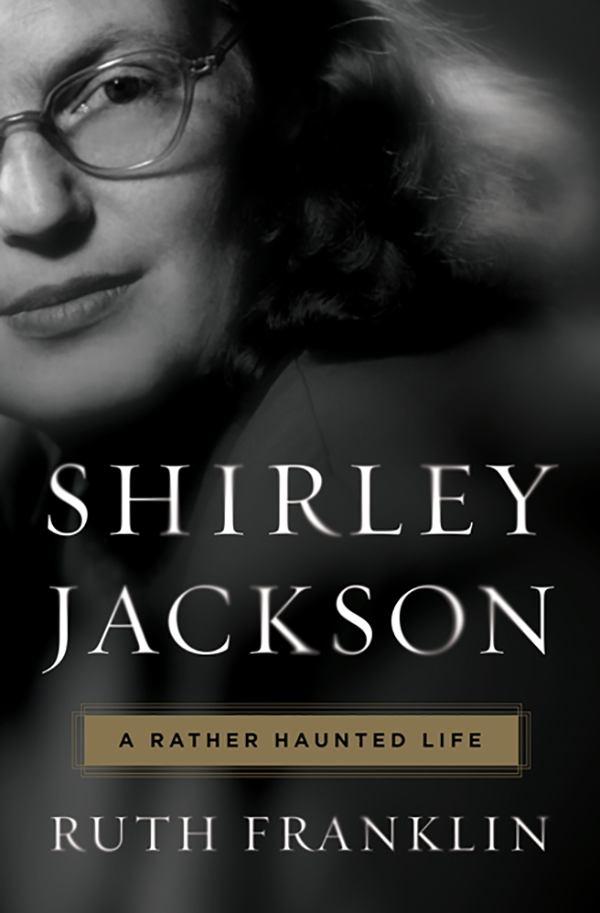

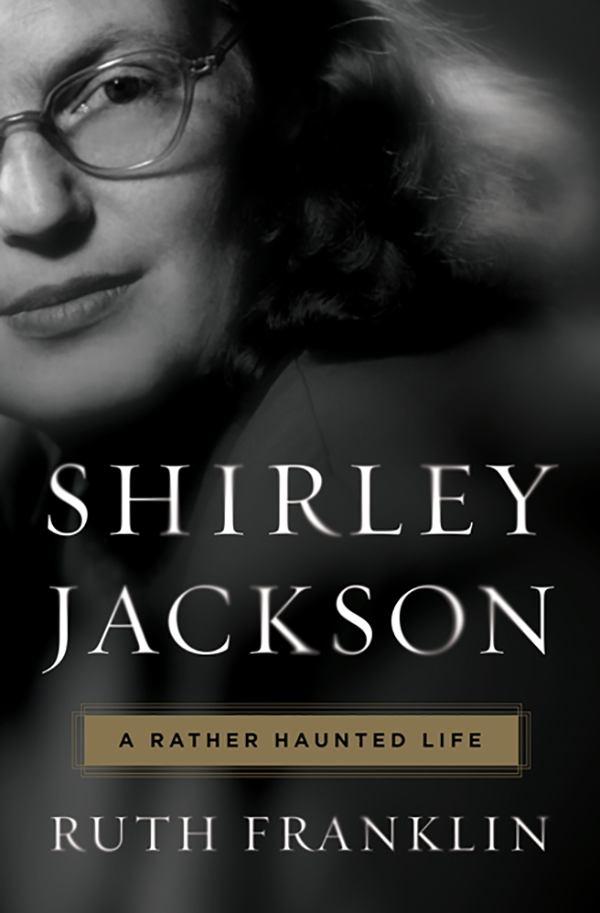

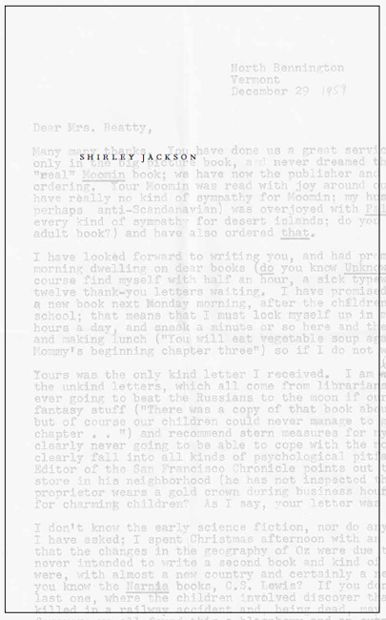

Frontispiece: Shirley Jackson by Erich Hartmann, 1947.

Copyright 2016 by Ruth Franklin

All rights reserved

First Edition

Since this page cannot legibly accommodate all the copyright notices, pages

58587 constitute an extension of the copyright page.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Coporation, a division of

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Barbara M. Bachman

Production manager: Louise Mattarelliano

Jacket design by Catherine Casalino

Jacket photograph Erich Hartmann / Magnum Photos

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Franklin, Ruth, author.

Title: Shirley Jackson : a rather haunted life / Ruth Franklin.

Description: First edition. | New York : Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016014711 | ISBN 9780871403131 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Jackson, Shirley, 19161965. | Authors, American20th centuryBiography. | Women authorsUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC PS3519.A392 Z64 2016 | DDC 818/.5409 [B]dc23 LC

record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016014711

ISBN 978-1-63149-212-9 (e-book)

Liveright Publishing Corporation

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

A SECRET

HISTORY

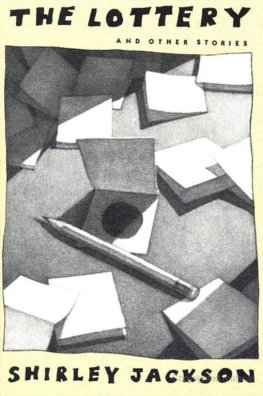

S HIRLEY JACKSON OFTEN SAID THAT THE IDEA FOR THE Lottery, the short story that shocked much of America when it appeared in The New Yorker on June 26, 1948, came to her while she was out doing errands one sunny June morning. She thought of the plot on her way home, and she immediately placed her toddler daughter in the playpen, put away the groceries she had just bought, and sat down to type out the story on her signature yellow copy paper. It was off to her agent the next day, with virtually no corrections: I didnt want to fuss with it, she later said.

As origin stories go, this onefirst told by Jackson and repeated countless times by othersis just about perfect. Its near mythic quality suits The Lottery, a parable of a stoning ritual conducted annually in an otherwise ordinary village. And it sets up the reader for the surprise that follows: the angry, confused, curious letters from New Yorker subscribers that would soon overwhelm the post office of tiny North Bennington, Vermont, where Jackson lived. Some of the letter writers rudely announced that they were canceling their subscriptions. Others expressed puzzlement or demanded an interpretation. Still others, assuming that the story was factual, wanted to know where such lotteries could be witnessed. I have read of some queer cults in our time, wrote a reader from Los Angeles, but this one bothers me.

There is only one problem with Jacksons origin myth. It is not entirely true. The letters are real, all rightJacksons archive contains a huge scrapbook filled with them. But her files show that certain details do not match up. The changes made to The Lottery were not as minimal as Jackson suggested they were; there is no evidence that Jacksons agent, as she would claim, disliked the story; and the period between submission and publication was a few months, not a few weeks. These details are relatively minor; they alter neither the meaning of the story nor the significance of its impact. But for the biographer, they are the equivalent of a warning siren: Caution! Poetic license ahead!

Some writers are particularly prone to mythmaking. Shirley Jackson was one of them. During her lifetime, she fascinated critics and readers by playing up her interest in magic: the biographical information on her first novel identifies her as perhaps the only contemporary writer who is a practicing amateur witch, specializing in small-scale black magic and fortune-telling with a tarot deck. To interviewers, she expounded on her alleged abilities, even claiming that she had used magic to break the leg of publisher Alfred A. Knopf, with whom her husband was involved in a dispute. Reviewers found those stories irresistible, extrapolating freely from her interest in witchcraft to her writing, which often takes a turn into the uncanny. Miss Jackson writes not with a pen but a broomstick was an oft quoted line. Roger Straus, her first publisher, would call her a rather haunted woman.

Look more closely, however, and Jacksons persona is much thornier. She was a talented, determined, ambitious writer in an era when it was still unusual for a woman to have both a family and a profession. She was a mother of four who tried to keep up the appearance of running a conventional American household, but she and her husband, the writer Stanley Edgar Hyman, were hardly typical residents of their rural Vermont townnot least because Hyman was born and raised Jewish. And she was, indeed, a serious student of the history of witchcraft and magic: not necessarily as a practical method of influencing the world around her (its debatable whether she actually practiced magical rituals), but as a way of embracing and channeling female power at a time when women in America often had little control over their lives. Rather haunted she wasin more ways than Straus, or perhaps anyone else, realized.

Jacksons brand of literary suspense is part of a vibrant and distinguished tradition that can be traced back to the American Gothic work of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, and Henry James. Her unique contribution to this genre is her primary focus on womens lives. Two decades before the womens movement ignited, Jacksons early stories were already exploring the unmarried womans desperate isolation in a society where a husband was essential for social acceptance. As her career progressed and her personal life became more troubled, her work began to investigate more deeply the kinds of psychic damage to which women are especially prone. It can be no accident that in many of these works, a housethe womans domainfunctions as a kind of protagonist, with traditional homemaking occupations such as cooking or gardening playing a crucial role in the narrative. In Jacksons first novel, The Road Through the Wall (1948), the houses on a suburban street mirror the lives of the families who inhabit them. In The Sundial (1958), her fourth novel, an estate functions as a fortress: an island amid chaos. In The Haunting of Hill House (1959) and We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962), her late masterpieces, a house becomes both a prison and a site of disaster.

Ive been fascinated by Jacksons work since my first reading of Hill House, which captivated me with the literary sophistication and emotional depth Jackson brought to what might have been a hoary ghost story. But it was only more recently that I began to appreciate the greater range of her work and its resonance with the story of her life, which embodies the dilemmas faced by so many women in the mid-twentieth century, on the cusp of the feminist movement. Jackson belonged to the generation of women whose angst Betty Friedan unforgettably chronicled in

Next page