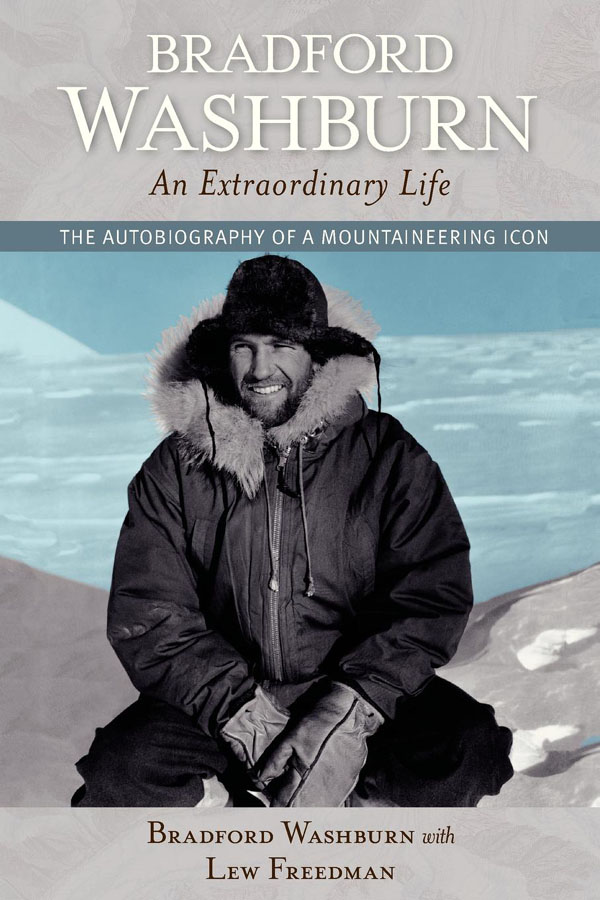

BRADFORD

W ASHBURN

An Extraordinary Life

BRADFORD

W ASHBURN

An Extraordinary Life

B RADFORD W ASHBURN

with

L EW F REEDMAN

Text 2005, 2013 by Bradford Washburn and Lew Freedman

All photographs Bradford Washburn unless otherwise indicated. Mount McKinley map on pages 168 and 246 printed by Swiss Federal Institute of Topography; The Heart of the Grand Canyon map on page 271 National Geographic Society; Mount Everest map on pages 185 and 284 National Geographic Society.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Washburn, Bradford, 1910-2007.

Bradford Washburn : an extraordinary life / Bradford Washburn and Lew Freedman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-88240-907-8 (pbk.)

1. Washburn, Bradford, 1910-2007. 2. MountaineersUnited States Biography. 3. PhotographersUnited StatesBiography. 4. Natural history museum directorsMassachusettsBostonBiography. I. Freedman, Lew. II. Title.

GV199.92.W35A3 2013

796.522092dc23

[B]

2013004999

WestWinds Press

An imprint of Graphic Arts Books

P.O. Box 56118

Portland, OR 97238-6118

(503) 254-5591

www.graphicartsbooks.com

Editor: David Abel

Design: Barbara Ziller-Caritey

For Barbara,

beloved companion for sixty-four years

B. W.

C ONTENTS

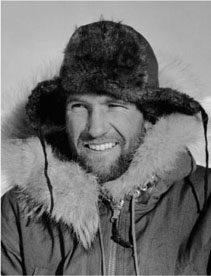

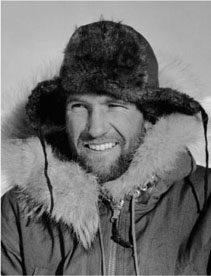

Sherry and I hiked up 6,288-foot Mount Washington during the summer of 1925. I was fifteen; Sherry was thirteen and a half. It wasnt the first time for me, and certainly wasnt the last. I still have a special love for that mountain.

C HAPTER O NE

M OUNTAIN B EGINNINGS

On the morning after my first great mountain climb, I woke early on the summit of Mount Washington in New Hampshire to see the sun rise over the Atlantic Ocean. It was a sight that I will never forget. You almost never can distinguish the ocean in the view from the top of Mount Washington, because it meets the sky as a continuous blue horizon. The exception is very early in the morning on a clear day, when the sun is glittering off the water; that reflecting light is the ocean. The year of the climb was 1921 and I was eleven years old.

For most of my adult life, I have been associated with Mount McKinley in Alaska, as a climber, explorer, photographer, cartographer, and scientist. At 20,320 feet, McKinley is the tallest mountain in North America. Few people know of my love and nearly lifelong association with the much smaller Mount Washington, at 6,288 feet the tallest mountain in New England.

Mount Washington, the king of the White Mountains, provided my mountaineering start in a low-key way. My cousin Sherman Hall, from Portland, Oregon (and a student at Yale at the time), invited me along for the climb. As a youngster, I had terrible hay fever: awful sneezing fits and trouble breathing. July was the worst time. My nose would plug up and my eyes would tear. It was just awful. My family had decided on a new place for a summer vacationRockywold Camp on Squam Lake in New Hampshireand Sherman joined us for a visit.

I knew nothing about Mount Washington. (I had previously hiked up a 1,200-foot hill called West Rattlesnake, which had a big rounded ledge and Ive always said that for the amount of energy put in to get there that was the best view in the world.) Sherman and I climbed up the famous Tuckerman Ravine Trail, spent the night in the Summit House at the top, and rose early. We were rewarded with that terrific sunrise and distant view of the ocean.

The climb was scrambling all of the way. This was not a technical climb like my true climbing beginnings later in the French Alps. We simply put one foot in front of the other on the trail, and hauled ourselves up over the boulders. It was fun; and I quickly realized that the higher I climbed, the less my terrible hay fever bothered me. Eliminating my hay fever actually played a very important role in my future as a mountaineer: the higher I got above sea level, the better I felt. Finding a place where I didnt have hay fever was a real thrill.

We climbed in the summer, so the weather was mild, but one of the fascinating things about Mount Washingtonand few world-class mountaineers ever give it a thoughtis its fearsome reputation for extreme weather. The highest wind velocity ever recorded was taken at the observatory atop Mount Washington: 231 mph.

If you put an observatory on Mount McKinley, you would probably record higher velocities than the Mount Washington record. But Ive always thought that there was something unusual about Mount Washington. It is shaped as a sort of dome, and if you went a thousand feet above the summit, there would not be as much wind as you get on top. I think the wind is squeezed up as it comes over the top, and theres more wind down on the lee side. You dont want to go fiddling around there in an airplane; its terribly rough on the lee side.

My interest in Mount Washington grew from that little climb with Sherm Hall. In midsummer of 1925, I climbed it again with two schoolmates. We climbed the Webster Cliff Trail and then the Southern Peaks Trail, and spent the night at the Lake of the Clouds hut. The next day we went the whole way over the northern peaks of the Presidential Range, and my parents picked me up in their auto two days later at Randolph, New Hampshire.

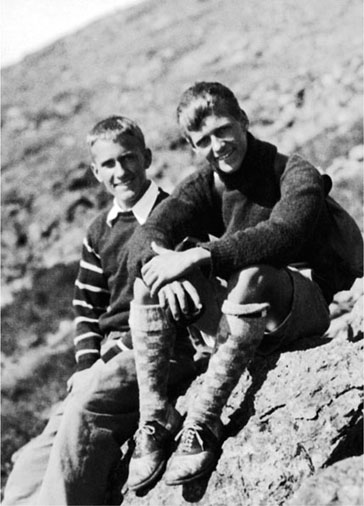

My brother and I were adventuresome boys from the start. Here were climbing our first mountain together in the winter of 1914, outside our home at 18 Highland Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

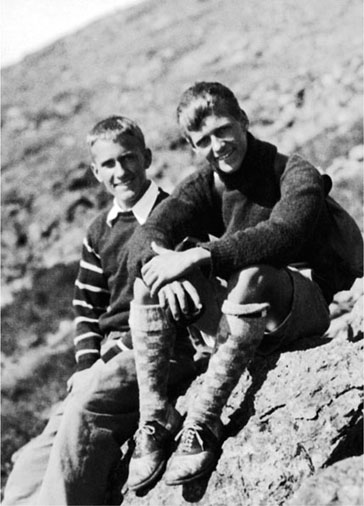

My mother took this picture in August 1925, as our little party was heading up the trail in the White Mountains. From left, Johnny LaFarge, Hunty Thom, me (at fifteen), and Hal Kellogg.

Then I returned to Mount Washington in the winter of that year for a Christmas climb with my father. We spent the night at the Glen House, and then walked up the road that runs to the summit, and then back down. Thats sixteen miles up and back on that road in winter. I know that Mount Washington auto road very well. We used to call it the Carriage Road; in the old days, that was what it was used forhorse-drawn carriages.

It was moderately cold that day; the temperature was probably in the teens. It couldnt have been too windy or we wouldnt have made it all the way. We wore heavy wool trousers, wool long underwear, and heavy flannel shirts. We didnt have parkas in those days, just a windbreaker of sorts as a top layer. If it got too cold for that, you just didnt start. We wore the equivalent of hunting shoes on our feet, with rubber bottoms and leather tops. We also wore several pairs of woolen socks, which were pretty darned warm.